-

Posts

307 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

2

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Iaido dude

-

Christian Ship Tsuba (Is This Really an Ono Kozeho?)

Iaido dude replied to Iaido dude's topic in Tosogu

-

This was my original post with the reference to Fred Geyer's article. However, I am stand corrected since according to his accompanying timeline and text, the 2nd style emerges in 1605 when Christianity achieves popularism and the original and vibrant 1st style with a composition that reflects the original Jesuit IHS symbol (alternating short and long rays) emerged in the late 16th century when the Portuguese Jesuits make first contact in Japan. According to Fred's timeline the first style appears in 1552, but this is based on the appearance of the iron plate qulaity and is not in keeping with the history of the early Akasaka masters. I don't think you can date iron tsuba by the appearance of iron because the Momoyama-Early Edo smiths were masters at forging the plate to look earlier in their attempt to express the Wabi Tea Culture aesthetics. 1624 is when Shodai Akasaka moved from Kyoto to Akasaka to found the new Akasaka school. I argue that the original tsuba I posted must be pre-1624 because the persecution of Christians begins in about 1614 and quickly intensifies in the following decade. Shodai would likely have stopped producing such overtly Jesuit IHS style tsuba by then. So, I call that this mumei tsuba Proto-Akasaka. The proposed timeline is not perfect, but it's pretty close. Dating is fraught with some element of uncertainty because the early Akasaka masters did not sign their works.

-

Christian Ship Tsuba (Is This Really an Ono Kozeho?)

Iaido dude replied to Iaido dude's topic in Tosogu

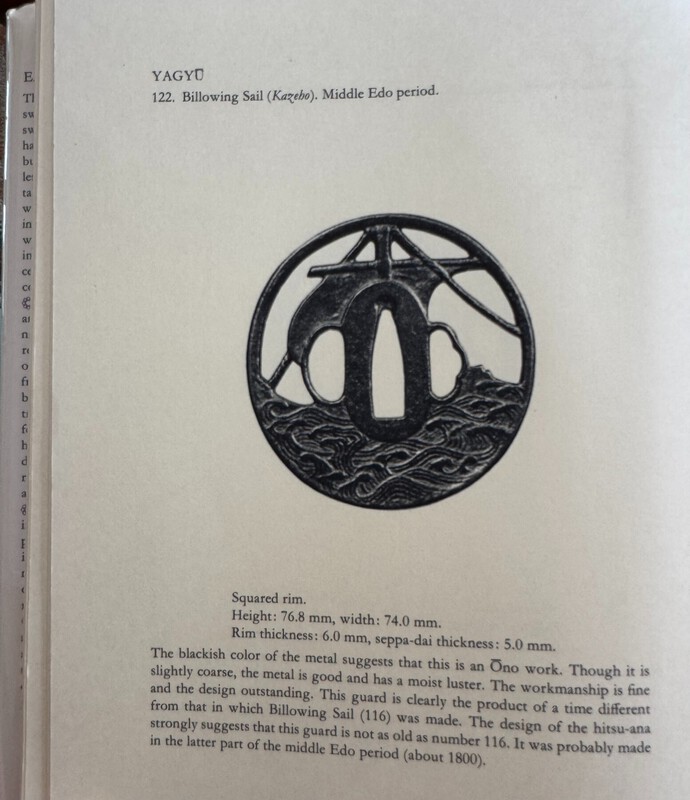

Sasano (gold book) has several examples of the Kozeho attributed to Ohno and Yagyu with the original simpler composition and without the crucifix on the stern. It may actually be an Ono design that became popular with Yagyu and subsequently included in the Yagyu design book as Kozeho. The meaning for the Yagyu Shinkage-ryu school of swordsmanship was that with sincere effort at practice one can "sail" to victory (something like that). -

This tsuba has just come on auction. It is familiar to many of us as being attributed to Ono with the motif of a sailing ship. This specific composition with the crucifix on the stern may be a reference to There are numerous such examples with similar attributions (e.g. Walter Compton Collection, Nakamura's Tsuba Shusei, various sellers and auctioneers) that are referring to the Kozeho motif seen in Ono and Yagyu work. However, I am skeptical and am hoping others will weigh in. It is suggested that this is a sailing ship transporting goods (Portuguese?) in the Ise Bay, Southeast of Nogoya. If it is actually a later work of the Edo period, what school can this whole genre be attributed to then? https://drouot.com/en/l/28349546-Japan-ono-middle-edo-period-1603-1868-iron-maru-gata-with-yo Mandarin Mansion (sold) https://www.mandarinmansion.com/item/ono-school-ship-tsuba Musees D'Angers (attributed "Owari" workshop) https://ow-mba.angers.fr/fr/notice/mtc-9025-garde-de-sabre-decore-d-un-navire-ce30b96a-7a07-43b8-b0c2-f8bbe1113315

-

I’m glad you both brought up the hinoki v. honoki issue. I successfully sourced out honoki specifically for saya-making that made the same comments. What is confusing is that elsewhere people write that there is no difference between these and that honoki is an incorrect term. I agree with you both. The other aspect of Japanese traditional woodworking that has come of my watching videos on making saya is the almost super-human ability to work with chisels and planes in hand to achieve such accuracy. I’m in awe of the skill that can be developed, but it is quite daunting for a beginner. I use a set of high quality Japanese chisels in my restoration work on guitars, but I’ve not had to develop this level of finesse.

-

Here is another Akasaka Shakoh tsuba I just acquired (en route from Japan) in the 2nd style with curved rays around the posts at 3 and 9 o’clock. There are bundo weights at top and bottom to acknowledge the Owari influence. The other rays are shorter than the early style and are of equal length. We see these changes in the composition as persecution of Christians begins and intensifies after 1624.

-

This is a skillfully carved ji-sukashi tsuba attributed to Kinai by Sasano sensei with his hakogaki. Kinai is brushed on the top of the lid, while the hakogaki with his mei is brushed on the inside of the lid. This tsuba really inspired my sukashi tsuba collecting starting back in spring 2024. It is difficult to part with it, but my focus has crystallized to Momoyama-Early Edo Owari Province sukashi tsuba with religious iconography. The early Kinai were heavily influenced by the Shoami style with ample movement. This one has alternating aoi (hollyhock) leaves and buds, which I interpret as symbolic of "life-death-rebirth." The carving has a wonderful and deep 3D quality to it. The iron is dark brown/blackish and smooth. I suspect that this "dished" tsuba is mid-Edo, but because it is mumei, it is very difficult to attribute to a specific Kinai smith. $800 + $25 (shipping in US) is firm. International shipping at actual cost. If you would like the custom display stand I made, it is an additional $30. Please PM me for more info and additional photos. 72 x 71 mm, 5.9 mm (mimi), 5.5 mm (seppai-dai).

-

- 6

-

-

-

I want to have a new says made for this iaito so that it doesn’t rattle on being sheathed during practice. It was a Japanese custom made iaito (1038 gm, 30” nagasa) gifted to me by my teacher about 20 years ago. Thinking of making the saya from hinoki myself, but it will be a steep learning curve. Besides, I am waiting for the arrival from Japan of a new super heavyweight Dotanaki style iaito. That one is slightly heavier. https://www.ebay.com/itm/312907878796?mkcid=16&mkevt=1&mkrid=711-127632-2357-0&ssspo=tE8UuHeOQ8K&sssrc=4429486&ssuid=HMDEU0GLQ0e&var=611625317890&widget_ver=artemis&media=SMS

-

Yes, one of the qualities that I appreciate about the Shakoh I posted is that with a medium-sized tsuba, it is 6.5-6.75 mm thick and weighs 133 gm--a very substantial guard. Perfect for shifting the balance point of a sword towards the tsuka. I have mounted a similarly monstrous Ohno chock full of globular tekkotsu on my practice iaito to inspire my practice and to achieve the desired balance.

-

Wonderful, Simon. There is no better way except by working through the process of handcrafting an object, in order to gain a very concrete understanding of how a traditional process was developed. I have been thinking of trying my hand at making a new saya for one of my practice iaito because after many years of use the fit has become a bit loose. Can you provide a description of how you made the saya starting from hinoki boards?

- 4 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- koshirae

- restoration

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Here is another example of a nice Akasaka Shakoh of the 2nd style with shorter rays, rounded rays around the left and right diamond posts, and small weights on top and bottom. This gets increasingly exaggerated so that Christian samurai can begin to say “Am I Kirishitan? No. Not my circus. Not my monkey.” It likely dates after 1624 when we don’t see the Owari influenced bundo weight motif anymore—replaced by straight or diamond posts.

-

Great point, Florian. The rim is rounded, but not radially like a true torus. I’m waiting for sunny weather to take a better pic to show this. The inner wall actually has a flat portion, but it is more rounded than Fred’s. His is flatter on the omote and ura surfaces—more like Owari. Perhaps the unusual quasi-torus shape of the mimi reflects experimentation—prototyping as it were. It creates a very robust and substantial effect even if this idea was ultimately abandoned by the Akasaka atelier.

-

I was under the impression that all of the Ko-Akasaka masters produced distinctively rounded rims. Mine doesn’t have the 3-layer puff pastry construction (mokume-game) that I have seen in Nidai Akasaka work. Using Deepseek AI query, it doesn’t appear that Shodai forged mokume-gane tsuba. This was developed by later generations starting with Nidai. Here is a possible prototype-Akasaka tsuba with features of Owari and Akasaka tsuba: https://richardturner.wordpress.com/2011/09/28/who-can-it-be-now/

-

The one from the Varshavsky collection on the lower right is in a later style in which the motif is being softened and disguised to avoid persecution. It is quite typical of the mid-late Edo period. These 1st style Early Edo Shakoh don’t look like clock gears. And both are proto-Akasaka, as I have argued from their features and historical context.

-

Tim, it certainly is a possibility. However, the Omura clan would have to have commissioned Shakoh tsuba from elsewhere. I'm not aware that the Hizen smiths of the Yagami and Nanban schools produced Shakoh tsuba. Most of the 1st style Shakoh were apparently Owari, Kyoto, or Akasaka tsuba. However, Fred notes that regions such as Hizen had extensive exposure to the Jesuits and it seems quite likely that the Kirishitan samurai wore Shakoh tsuba in declaration of their faith.

-

I think that the Japanese in the era that we are discussing new very well the difference between Zen Buddhism and Christianity, but it is an eastern mindset to be able to embody the "both/and" rather than the "either/or." Whether Buddha's amida-yasuri halo or Christ's halo, they speak to commonalities and shared values. Moving from Buddhism to Christianity is not like leaping off a cliff. It is more like a "soft shoe" to the right. My grandmother in Taiwan was a Buddhist, Catholic, Taoist, and Ancestor Worshipper. Each tradition had something valuable to offer to different aspects of her life. Chinese and Japanese don't operate in dichotomies. Now, whether modern Japanese tsuba collectors can discern the difference between an amida-yasuri Hoan, Shakoh Akasaka, and Edo generic clock gear--that is another thing altogether.

-

That Japanese motif often seen in arts and crafts is also called “myriad treasures.” The bundo weight is frequently seen in Owari Province tsuba of the Momoyama and Edo Periods, connoting strength and balance. And it is depicted exactly as it existed in the real world. Here is a copper one from the Edo Period. And here is my Kanayama tsuba with gourds and bundo weights (chock full of lumpy-bumpy tekkotsu).

-

The paper to Owari is just plain wrong, if you are referring to my tsuba. It’s not an Owari. It is clearly Akasaka. Fred's is attributed to Shodai Akasaka, although he feels that it may be earlier. The features and historical context point to Shodai or Nidai for both (they never signed their tsuba, so this attribution must be inferred).

-

It’s a great question. The counterweight is one of the seven treasures in Japanese mythology—auspicious items that have a Buddhistic significance. It also connotes strength and is a commonly used motif in the composition of Kyoto, Owari, and Kanayama works. One of the reasons that the Shakoh imagery is so assessable to the Japanese of that time is that it is very similar to the amida-yasuri imagery of the Buddha. So, we may be seeing a joining of Christian and Buddhist imagery. Fred’s is the only other Ko-Akasaka Shokah tsuba with bundo weights.

.thumb.png.10a300fca786a7d956d6a8a5acd2649c.png)