John C

Members-

Posts

2,745 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

18

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by John C

-

Not sure. Pic was supposedly Vietnam era. Does look like a single engine prop. John C.

-

-

Been there. The guy who sold me the souvenir swore it was just a late war kai gunto using left over parts. I knew what I was buying so it didn't matter - this time. But what if someone didn't know. Everyday there are standard soldier's tanto being sold as "kamikaze suicide" knives when the sellers know full well that isn't correct. Just buzz words to catch different searches. John C.

-

'_______ Gift' Admiral's Dirk Translation Request

John C replied to matthewbrice's topic in Translation Assistance

I had to google it - for those who didn't: Onshi (“imperial gift”) and Wakatsu (“presented to you”) John C. -

Lex: I'll chime in here. Just from those pics, the obvious signs are: 1) the bo-hi is tapered at the end (like using a grinder) rather than cut straight down. 2) The bend of scabbard latch is exaggerated (real ones are straighter). 3) The sarute is too long, which is typical on fakes Hope this helps, John C.

-

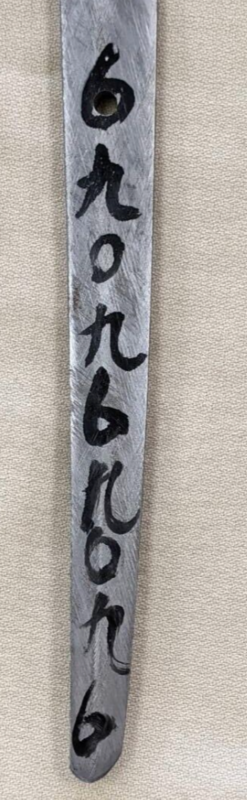

Additional info: All of the parts on my #66 are marked; the habaki with roman numerals and the tsuka with Japanese numbers. John C.

-

Souvenir sword with fake blade?

John C replied to John C's topic in Auctions and Online Sales or Sellers

Update: Sword sold for 1,101 dollars. A bit much for a souvenir in that condition. But as noted above, some folks just have to win. John C. -

Help with single character on carved model of Cruiser Izumi

John C replied to tbonesullivan's topic in Translation Assistance

-

Looks like the sword is dated 1939. John C.

-

Type 98 Shin Gunto - Navy arsenal blade

John C replied to Whitecap's topic in Military Swords of Japan

May be of interest - a Takeyasu in Kai gunto fittings. Note the really large assembly number. https://www.ebay.com/itm/305147883374?hash=item470c3b2f6e:g:5HwAAOSwA71kGKm7&amdata=enc%3AAQAIAAAAwAJyVVdat78P%2FLcavGGqQTkzxcEDU41MoweMIg6Dpu4FZrDWR5rnOEQm0wJZoG8HJ9KNIYRiLghXe22WlWCFvfyyy%2FVnNepTcF2qoH4HqWkVLG1LTJZZzuW4TquCYXI%2Bc%2Bu98NsZzsA9bx51kl0%2BSg3E9wVVGomN5w1GWg6bnMKUw6MoePJ4ZTEqv05HKZxB%2F12C73iV5dZ8Zcmt5CX05C%2FO2ftLwpA0m0K4El3fOe%2BY%2BwUt15lxoXZ9CcE03WqrmA%3D%3D|tkp%3ABk9SR5bTtbLaYg John C. -

PM sent. John C.

-

@Bruce Pennington Showa22 has a "inanami" kai gunto with a host of marks on it. Thought it may be of interest. https://www.ebay.com/itm/364492652154?hash=item54dd747e7a:g:GS4AAOSw~O9lDN1q&amdata=enc%3AAQAIAAAAwIGBaJKqSnHpQVCmcr1xoEoHhUJQTVbDL6S%2BrDbTGnBVanqg9iw712tPcWrdBvS3KpazRkRXElqs%2Bz9C8yF3LGUvlhEcxK1JZARQzL6bTdtmNQ4M461bVnjcWlk0CMWnfAeglPd%2BKs8JYMGDIz6fvpFf6GKXrzf5QEkVIkkJAg8XZy59JtuNK6hns46Pmx2zHXo4h4sd3%2B5LXMQuJepZ%2F%2BNPWLoWbbAHcKeRPjgAhBZKf%2BoApRSdOtPPPIx0NH8qTw%3D%3D|tkp%3ABk9SR9Cp16_aYg John C.

-

The picture you took with the magnifying glass looks like the start of a date (sho). Do you have a picture of the entire nakago (tang)? John C.

-

Marcus: I don't sell swords, however I buy a lot! I think Bruce is correct. You may consider selling the sword as is since the profit margin after repairs would be about the same. John C.

-

That could be for a Japanese type 19 (or possibly a type 8 )army saber. John C.

-

Okay. So not common but not suspect either. John C.

-

Thanks for the info, Piers. Not really my thing (yet!!!). I would need to do a whole lot of studying first. Just thought it could be of interest to you all. John C. p.s. I did watch the video of you (?) firing the matchlocks. Very cool.

-

-

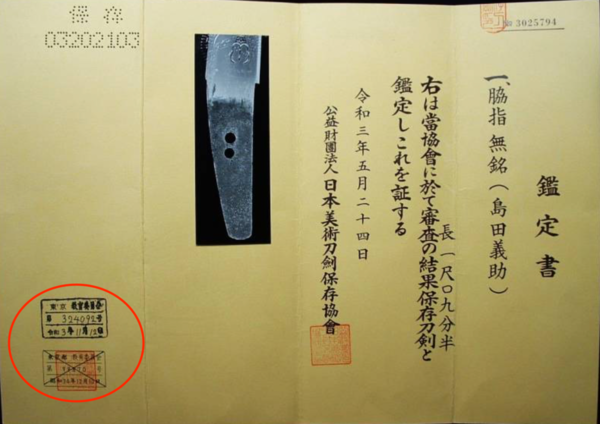

I am assuming this (circled area) is some sort of correction to this origami. Has anyone seen this before? John C.

-

WW2 Japanese Sword Museum Grade Shin Gunto Kanemichi

John C replied to Swords's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Could be traditionally made because I don't see any seki or showa stamps. But I also don't see a star stamp or defined nioi on the hamon. If I had to flip a coin on a sword dated 1943, I would lean toward showato. Remember too that many RJT smiths also made showato - but did them very well. John C. -

WW2 Japanese Sword Museum Grade Shin Gunto Kanemichi

John C replied to Swords's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Steve: I can't make any judgement on authenticity, however I think 5 grand is a bit much for a showato - even one in mint condition. But if you are a Kanemichi collector, then a mint example would be the pinnacle of your collection. John C. -

Here is a good website that describes the origami. http://www.japaneses...ndex.com/origami.htm I can see a watermark on yours. And it looks similar to one given as an example on the above website. John C.

-

-

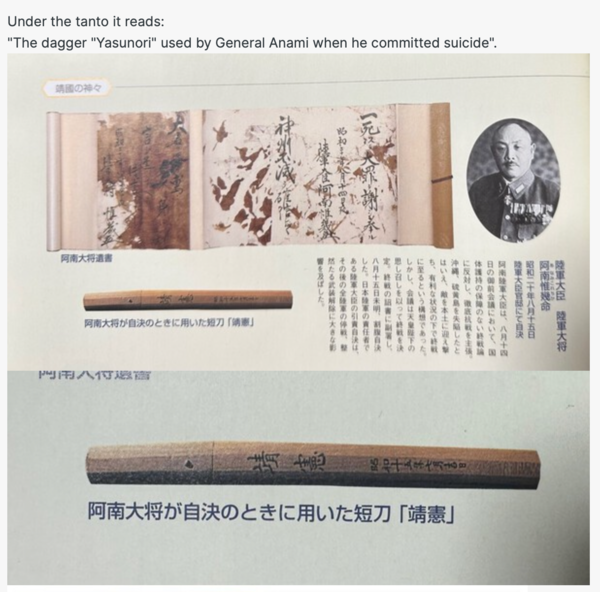

Ron: Based on some of the research I have done, these tanto were ordered by soldiers and came in a variety of quality; everything from a piece of mass produced sword tip to a Gassan Sadakatsu (see below). Most came in shirasaya, with some having a leather cover. Below are some examples of others. John C.

-

Is it a clan mon and if so, which one?

John C replied to NewB's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Just some additional info - I forget which family was using the mon with 2 lines in a circle, however it was supposed to represent two clouds passing in front of a moon. John C.