-

Posts

798 -

Joined

-

Days Won

1

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by reinhard

-

Peter, before checking details of the mei, you better start with the characteristics and the quality of the work itself. First you need to know when, where and how SORIN worked before checking tiny details of a mei. For his biographical background (quoting): "Egawa SORIN was born in Mito in 1774. He began as a highly renowned metal worker by the name TOSHIMASA. Later, becoming heir in-law of Katsura EIJU who was a leading disciple of Yokoya SOYO he succeeded in combining the two different types of carving methods of Yokoya and Mito schools." You will find a representative example of his great skills in the koshirae (tokubetsu kicho koshirae) he made for a blade by UNSHO. It was lot No.261 in the first of three auctions selling the Compton-collection (Christie's NY, 1992). The two mei on kozuka and kogai from this koshirae look like this: reinhard

-

There are no Kokuho (i.e."National Treasure") blades from ShinTo or ShinShinTo times. Juyo Bunkazai ("Important Cultural Property") is the highest level the best of them have attained. However, Ippei YASUYO is a very famous name, his work is extremely rare and faking his mei has been lucrative therefore. Your example is showing a rather poor attempt of doing so. reinhard

-

NBTHK and NTHK are confused here. Neither European branch nor American branch of NBTHK are offering shinsa. The two sections consist of members only. We are neither qualified nor authorized to hand out papers. Papers are handed out only by the headquarter in Japan for good reasons. NTHK on the other hand is sending people abroad for expertise. reinhard

-

Pic one: Egawa SORIN (+kao) made this when he was 71 years old. Egawa SORIN is a very big name and his (potential) works need to be cross-checked very carefully. reinhard

-

Brian, I'm still owing you an explanation. In 1993 the people of Inakudate, Aomori prefecture, tried to find a way to revitalize their village. After experimenting with old and new sorts of rice, they succeeded in creating an image of Mount Iwaki. This image was repeated for the next nine years. Not exactly an example of "Japanese aesthetic for artistic detail" but of painstaking labour following rather simple patterns. In order to attract more tourists design had been changed and the whole thing finally ended up as an attempt of becoming a kind of rural Disneyland for simple minds (see pic attached). Recently there was a local argument about renting parts of the rice-fields for commercial logos (Japan Airlines). Finally it was decided not to. With this background my post might not be that cryptic anymore. If yes, please PM me. reinhard

-

Andrew, it is probably best to pass on this one. Many reasonable objections have been made. Just in case you are interested in some more: Very thin katana with "fragile" o-kissaki are most often pointing towards naginata-naoshi katana. On real tachi from Embun to Joji era, kissaki are usually well defined even after many polishes. Especially mitsu-gashira (point where shinogi, ko-shinogi and yokote meet) should be easy visible. Not so on naginata(-naoshi), for there has never been a mitsu-gashira from the beginning. Suppose you are dealing with a naginata-naoshi katana, kaeri (turnback of hamon) is the next thing you should look at. Old naginata-naoshi katana usually have little or no kaeri, for the uppermost part of the blade had to be cut off from the mune side in order to straighten the strong sori. - This particular katana displays a very long kaeri though. - Looking at the nakago next, it is covered by very odd rust and patina. Actually it looks very much like a retempered blade. Sori is adding to this impression. Katana in the shape of naginata-naoshi were also made during later periods, especially during ShinShinTo, but their appearance is solid, thick and strong. - As for hada and hamon, nothing valid can be said on the basis of these pics. reinhard

-

Much ado about a poorly faked mei, don't you think? reinhard

-

Garage sale find Need help with Mei

reinhard replied to Greenkayaks's topic in Translation Assistance

For consideration: nidai KANESADA added his mei very close to the nakago-mune, almost touching it. He kept doing so after changing his name into TERUKANE. reinhard -

-

More questions than answers.

reinhard replied to xxlotus8xx's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

No doubt about that. reinhard -

More questions than answers.

reinhard replied to xxlotus8xx's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Since there was only one YUKIMITSU in Sagami, THE YUKIMTSU, who worked around late Kamakura period and made no wakizashi at all, for they had not been invented yet, this should not come as a complete surprise to you. Because of the afore-mentioned reasons this is not really interesting but showing that even most fakers have a minimal knowledge when it comes to big names. BTW Some genuine mei by YUKIMITSU did survive on tanto. Unfortunately none on tachi though. In short terms: You're looking for a faker as stupid as the guy who carved the mei on your sword. This doesn't make sense to me either. reinhard -

Interesting tsuba for sale

reinhard replied to Wickstrom's topic in Auctions and Online Sales or Sellers

No need to tell. reinhard -

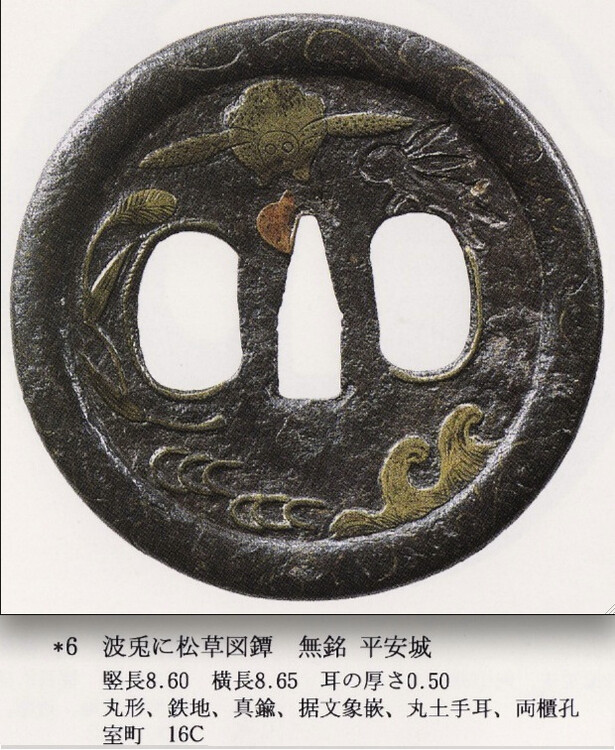

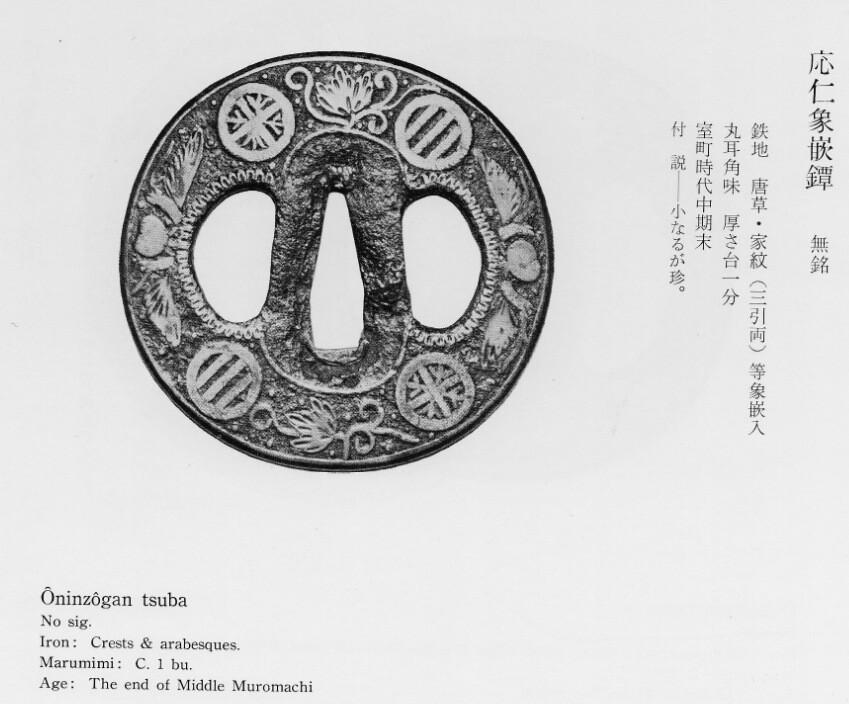

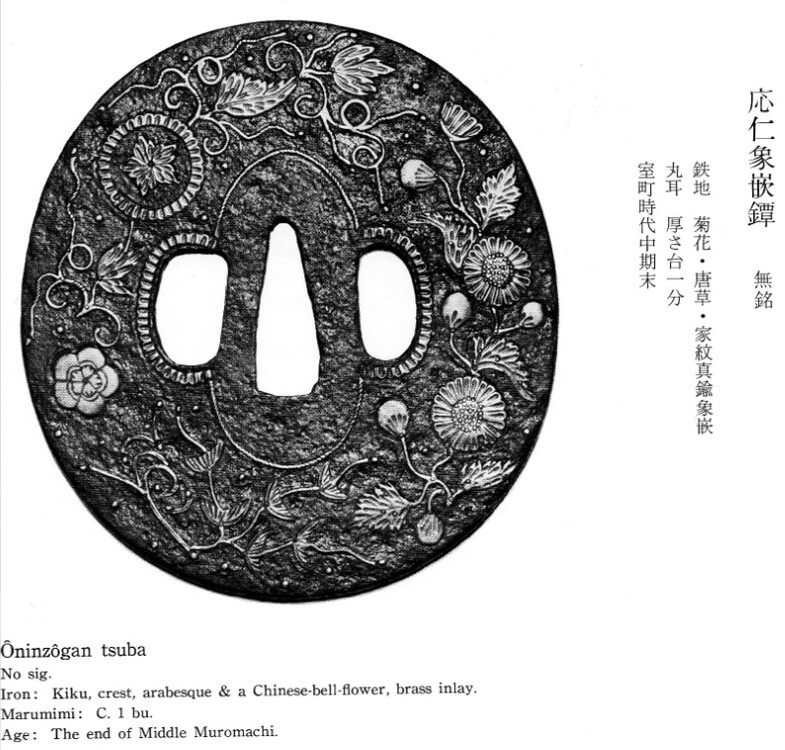

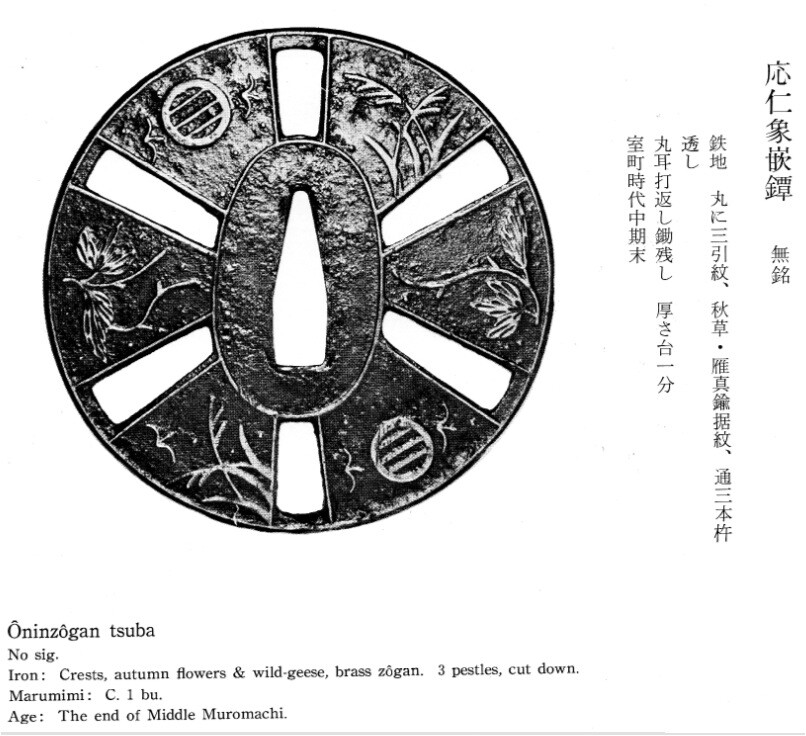

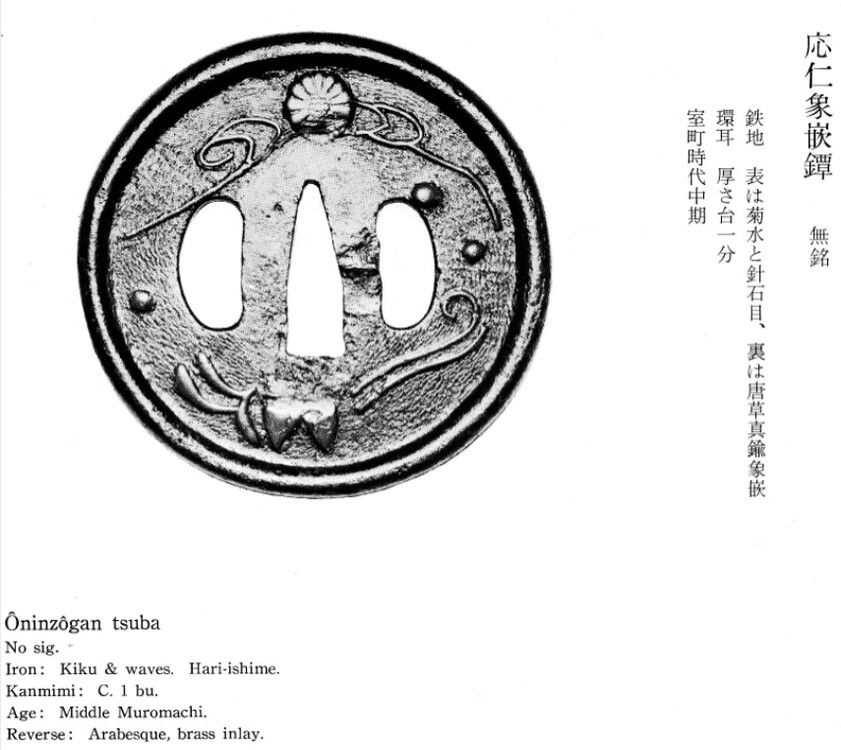

I didn't mean to step on anybody's toes. It was my intention to show the differences between early stages of tsuba-making, especially early attempts of pictorial design with inlays of colored metal, and crude fakes from later days. Distinction-line is not always obvious. Onin-zogan and Heian-Jo tsuba from middle to late Muromachi-period often look crowded, disorderly and far from refined taste. Compared to better examples of Ko-Kinko workers they have a rather naive and clumsy air. Nevertheless they are part of the history and development of tsuba. Personally I'm interested in a more refined style, but we should make and see the difference between early stages of development and sheer lack of craftsmanship of later fakes. Joe's tsuba has the potential to belong to the first category. The examples that followed have probably not. - Good stuff to start another thread with, but anyway. Here's a nice example of an early Heian-Jo tsuba from the former Lundgren collection. Crude workmanship and far from any refined taste, but still a "nice" example for early attempts of pictorial design. reinhard

-

By saying "nice" I didn't mean to reveal my personal preferences. It just meant: "Possibly genuine" which is meaning a lot nowadays and on a public forum like this. My dear Hobbit friends: Put your Western preferences aside for a moment and try to anticipate the taste of samurai during middle to late Muromachi period. Here are some examples. BTW Henry, you are probably associating Onin-zogan with ten-zogan ("nail-head zogan"), but there is more to it. reinhard

-

Joe, Text says: kuni fumei ("origin unknown"), teien-zu ("garden design"), followed by specifications,measurements and saying it's mumei. - Despite of some acid-crazed commentaries, this looks like some nice tsuba between O-Nin and Heian-Jo style to me. reinhard edit: Henry and Guido were ahead of me. Sorry for repeating.

-

What makes them think so? Ko-Nyudo KUNIMITSU's work is very difficult to track for he left hardly any signed works. Actually Uda KUNIMITSU is close to a mere myth. Even the experts of N.B.T.H.K. prefer to speak of Ko-Uda instead of Uda KUNIMITSU. Your friends must have good reasons to be so precise in their statements. Let us hear. reinhard

-

Andrey, Your latest pics are probably posted in order to show strong tekkotsu, especially in the rim. Unfortunately these kind of "bones" are not necessarily a hint for old age or quality. Although tekkotsu are a important factor to determine a tsuba's quality, this kind of mixed steel steel was in use during late Edo-period and later, leading to many confusions. Proportions, weight, asymmetry and surface of this tsuba leave me with no other conclusion than before. reinhard

-

Shrine Blade Plaque Translation please help?

reinhard replied to ludvig75's topic in Translation Assistance

It looks like a very cheap bait. You better go public with the full sword now. reinhard -

These measurements are pointing towards a Katchushi-style tsuba being reminiscent of older examples and the "good old days". Taking into consideration steel quality, patina, surface finish and other features on the basis of your pics, this tsuba was probably made during Bakumatsu. It aires the revivalist spirit of these days. Lack of craftsmanship combined with a tendency to exaggerate is typical. I can't help you with the signature, I'm afraid. reinhard

-

"Nice bo-hi" (whatever that's supposed to mean here) and "nice shine" are of less to no importance when buying a genuine NihonTo. You better think about it again. Is that what you really want? reinhard