-

Posts

113 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

1

Everything posted by Tim Evans

-

Cleaning corrosion off tsuba represents an element of risk because it is not possible to tell if the patina and/or base plate is damaged underneath (probably should assume some). If it is extensive, then you may need to have a professional address the damage and repatination. The first step is to decide if this tsuba is valuable enough to require paying a professional to restore it. Verdigis is usually a copper chloride or copper sulfate compound That said, if you decide to clean the verdigis your self, I have had some success with the following approach: Step 1 is to soak briefly in alcohol to remove any accumulated oils from handling. Step 2 is to soak in room temperature DISTILLED water. Distilled water should be just H2O with no dissolved minerals or chemicals such as chlorine Distilled water is commonly available in the US because it is used in steam irons. Not sure if available in Japan The verdigis can dissolve in the distilled water, so it will need to be changed every few days The process is slow, it may take weeks or months depending on how extensive is the corrosion. That also makes it controllable so you can stop doing it when an acceptable level of reduction is reached You are just soaking it in water so that should not otherwise damage the tsuba. That is assuming that the black color has not been touched up using ink or paint, which might come off with either the alcohol or water Your mileage may vary

-

Some brief notes about kogai Age – As with most pre-Edo fittings, there are no known signed examples, so dating is speculative based on a few intact jidai koshirae examples. However, there is a classification called Jidai kogai that are dated frequently Muromachi - Nambokucho periods Terms: Kanagu = tsuba, seppa, habaki, fuchigashira, metal saya fittings if any Kodogu = kogai, menuki, kozuka Mitokoromono = a kodogu set with all three pieces made with a unified theme Iebori = house carvers. Worked as retainers to Daimyo Machibori = street carvers. Independent metal workers who sold to anybody There were different ranks of Samurai There were also members of Buke clans who were not Samurai but who were allowed to carry swords Non-Buke people also were sometimes allowed swords. Generally restricted to the shorter lengths Koshirae and kogai (based on review of existing illustrated examples) Tachi – Have kanagu, but no kodogu (except menuki) Katana and uchigatana– Usually both kozuka and kogai or, neither. Some rare exceptions with either one or the other Wakizashi – Usually kozuka only or, neither. Also rare exceptions, usually from late Edo period Tanto – Usually both kozuka and kogai or, neither. Hira-zukuri blades may also have been mounted as ko-wakizashi and have kozuka only I have not found a definitive explanation for the kogai. Although kogai are thought to be a grooming tool, it is also thought to have functioned as a Buke rank identifier. This could explain why it was mounted in the saya so it was visible The theory is that kogai were allowed only to upper rank Samurai and Daimyo and forbidden to low rank Buke and common people It is thought that kogai were made primarily by Iebori workers for Daimyo and their higher ranking retainers. Frequently made as mitokoromono Kogai, as noted above, were mostly mounted on upper class Samurai katana and tanto koshirae Lower class Buke and commoners primarily wore wakizashi koshirae, no kogai Edo period machibori koshirae, which can be very luxurious and high end, are generally kozuka only wakizashi koshirae, with some exceptions for Daimyo quality koshirae More information on koshirae in general, and a reference book list can be found in the NMB archive in an article by me, titled, A Brief overview of Japanese Sword mounts of the late Muromachi through Edo periods

-

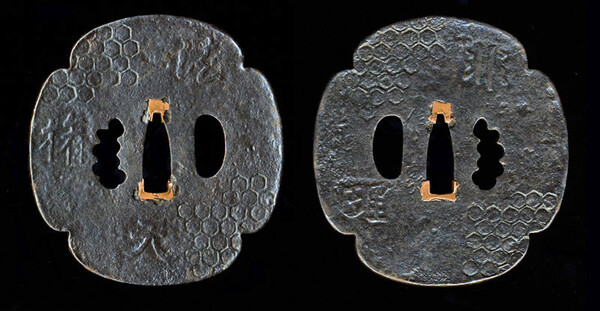

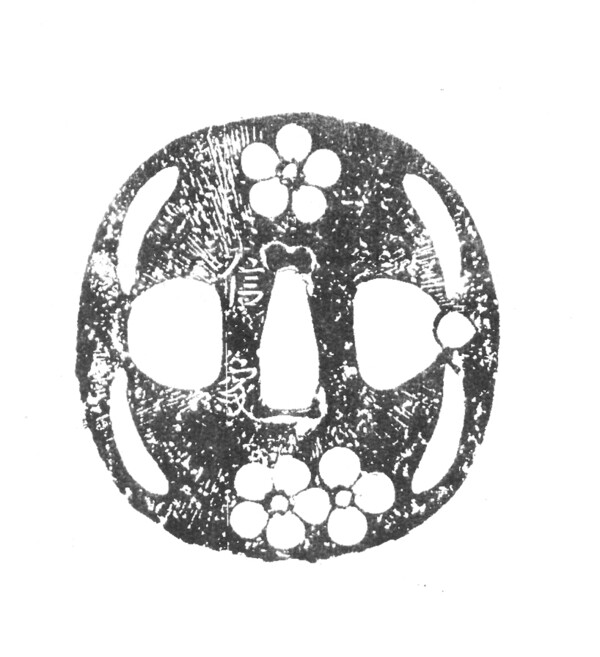

Same pattern tsuba is on page 459 of Higo Kinko Taikan, signed Tani of Hishu. This one does not show much age so either it is way overcleaned and repatinated or else a modern copy.

-

Oldest piece of Japanese art

Tim Evans replied to kissakai's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Small cast bronze tsuba of ascending and descending dragons. These are usually classed as kagamishi, but who knows who made them. Dating on these early cast tsuba is speculative, but this one was tagged as Nambokucho period in the 2019 KTK catalog. Photo credit: RKG. Tim -

Hi Peter, Unfortunately I don't own it. It was on a Niten koshirae I should have bought but did not. Including a few more images that I saved (note they put the tsuba on backwards!) I do have this tsuba signed Masa Kata (Probably Satsuma, about 1800). This is on a later Niten koshirae, the blade is dated 1781. The one you posted looks European influenced as well. Is it brass? Tim

-

This one looks European inspired to me but not sure if a maker/school can be identified. Cup shaped. Tim Evans

-

Hi Ford, I agree with your comments on Koren's book, which is why I did not mention it by name in the post above nor in the recommended reading list in my post of 16 September 2018. These contemporary books and magazine articles on Japanese aesthetics demonstrate that the popular meaning of these words changes over time, so, some caution or skepticism is required. If we are discussing the influence of cha-no-yu on sword fittings then delving into what the Muromachi-through-Edo Period Buke thought about it is the correct approach. The books by Michael Cooper, such as Rodrigues the Interpreter: An Early Jesuit in Japan and China would be an excellent start. I was mostly attempting to answer Steve's question about when "wabisabi" becomes a chic, trendy, hipster buzzword, both nationally and internationally. Tim Evans

-

I think I first encountered "wabi-sabi" in a book by Leonard Koren, published in 1994. I do not recall seeing it in anything written in or translated to English prior to that, so I assume Koren probably picked it up from the Japanese he was consulting with when he was researching the book. So, probably a late 20th century origin? And yes I do find it rather kawaii. Interesting that the thread still has legs Tim Evans

-

This device or something very close to it is identified as a mon In Chapplear's book, Mon the Japanese Family Crest on page 96 with the following entries: Name - Kurosu Clans who used it - Shimazaki and Tsuji No entry in Papinot for Shimazaki, but has the following to say about Tsuji: "Samurai family of the Hiroshima clan (Aki). Made noble after the Restoration - Now Baron".

-

Koshirae Having Belonged To Sakanoue Tamuramaro

Tim Evans replied to myochin's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

A picture of the tsuba is in this book. Bushi no Issho: Sukashi Tsuba by The Sanno Museum. Number 5, page 14. http://www.japaneseswordbooksandtsuba.com/store/books/b513-bushi-no-issho-sukashi-tsuba-sanno-museum Tim Evans -

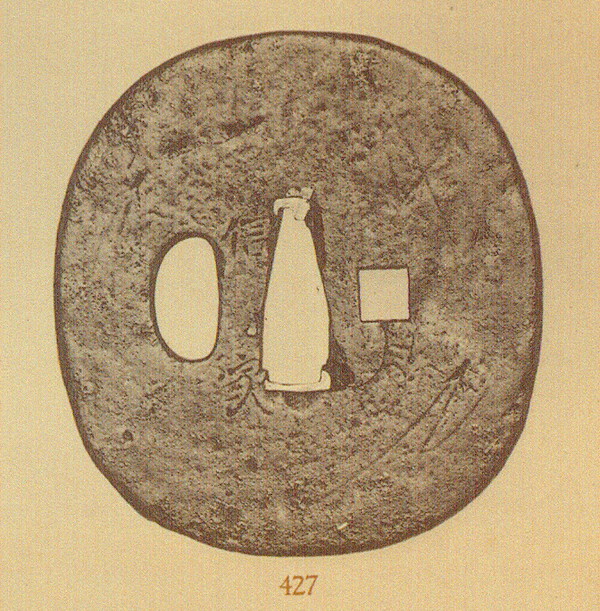

Thanks for the post Steve, that is a good example. Here is another that I published in the 2017 KTK catalog that I think demonstrates intentional sabi. The description in part... "The nunome decoration is a thickly applied, very high karat gold and is suggestive of the gold lacquer repairs seen on cracked tea bowls. The purpose of the gold nunome is to invoke a sense of sabi. The fan papers sukashi (gigami) design was used as a mon by several Daimyo, but also recalls the artistic pastime of painting the fan paper before mounting on the fan ribs". Although the gold nunome looks random and sparse, it is all there. These are not the remnants of a flaked off decoration.

-

"Impermanence or permanence, depending on your point of view?" That is very Buddhist. Very nice tsuba.

-

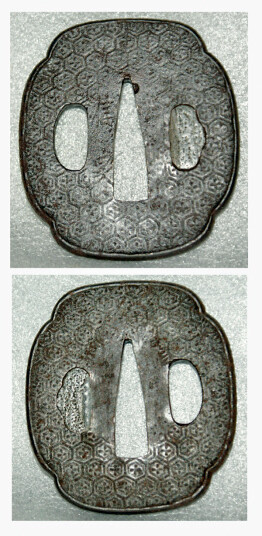

The design is a shippo pattern, which refers to "seven precious things". It was used as a kamon by several families. Based on the one image, I agree that that the smith intentionally made the tsuba in a rustic/sabi expression, which is considered to be informal. The presentation of the design, however is formal, so the overall synthesis is semi-formal. A good book on kamon is useful in deciphering these designs. One I like is Mon - The Japanese Family Crest by Kei Kaneda Chapplear.

-

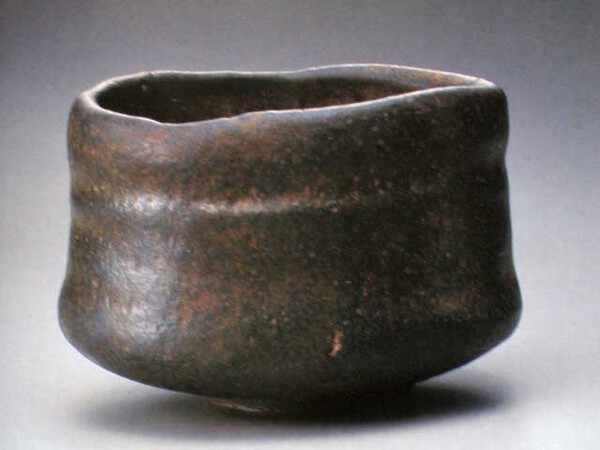

Some additional thoughts on the topic of sabi Many of the more recent attempts to explain sabi go to the “mellowed by use” idea that implies that these objects have wear and deterioration due to age and use, and since many of the objects that have been identified as having this characteristic are now old, there is an assumption that sabi equals antiqueness. What must be understood here is that there are intentional sabi objects were made to look the way that they look from the start, so their original appearance was not due to the accidents of time. D.T. Suzuki points this out in Zen and Japanese Culture: “When this beauty of imperfection is accompanied by antiquity or primitive uncouthness, we have a glimpse of Sabi, so prized by Japanese connoisseurs. Antiquity and primitiveness may not be an actuality. If an object of art suggests even superficially the feeling of a historical period, there is Sabi in it.” What can be confusing is that there are old deteriorated objects that are also referred to as sabi, but the original appearance and intention of the maker was very different. For example, kotosho and kokatchushi tsuba. Unlike later iron tsuba, the preferred appearance in the collector community of these two classes of tsuba is to leave them crusty looking in order evoke the sense that they are 600+ years old. We do not know what the original appearance of these tsuba looked like, my impression is their surfaces were originally much smoother and cleaner than how they typically look now. They acquired their sabi by accident rather than by design. There is also confusion about two Japanese words that sound like sabi. There is one that refers to oxidation, such as when the term kin-sabi (gold rust) is used. The other one refers to specific appearance characteristics of objects that will be explained further on. Because of its relationship to objects, we are on firmer ground in discussing sabi in regard to sword fittings than wabi. Here is a quote from Sadler’s Cha-No-Yu that may be a good starting point (In reference to Honami Koetsu): “As a lacquer artist he mixed brilliant gold with dull silver and lead on his writing cases and incense boxes, bringing a feeling of the ’Sabi’ of the Higashiyama age into the gorgeous fashions of Momoyama.” So, “sabi” is a form of elegance with a particular antique “look” that was valued by the Japanese upper classes in the 15th and early 16th centuries. In Cha-no-Yu, it was introduced as a part of the earlier shoin-cha and re-emerged with daimyo-cha (which evolved shortly after wabi-cha). As Plutschow states in his book, Rediscovering Rikyu: “Under (the Daimyo tea masters) Enshu and Sekishu, Confucianism gradually replaced Buddhism as tea’s underlying philosophy. Confucianism and Neo-Confucianism were about to become the official Tokugawa ideology and even Rikyu’s direct descendants, the so-called Senke schools, could not avoid it. Thus Rikyu’s tea changed from wabi to kirei-sabi.” Impermanence is a cornerstone of Buddhist teaching and practice; a key fact of reality that must be dealt with. I believe the intent of objects made with sabi characteristics is to acknowledge, accept and celebrate impermanence. This was why the characteristic of sabi as expressed in objects was valued, particularly by Buddhists and Warriors. One way for sabi objects express impermanence is to show process, in that we can see how they were made, and/or in that they (deliberately) look a little unfinished. For example, the yakite effects on Yamakichibei tsuba, which are semi-accidental and provide interest and movement in a natural way. There is also the process of time. Sabi objects were deliberately made to look old and worn. This is not the same as naturally deteriorated. Carving, inlay and onlay were rubbed down make them look gracefully aged and used (what is contemporarily called in the antique business, "distressing"). Also, repairs, such as sekigane were created for effect. This is sometimes difficult to judge if the effects were done well. On thing sabi is not, is crudeness, as in poor workmanship or materials. Made-as sabi objects were very sophisticated, and probably expensive, and the quality of the work will be evident when examined.

-

Yanagi has some interesting and helpful observations and stories, however, there are some of his speculations about the history of the objects, and who made them and why, that I think should be treated with skepticism. I fully agree that to appreciate the Japanese aesthetic principles being discussed, that it is very important to understand the cultural context. This would be late Muromachi to Early Edo Period Japanese culture. The cult of Cha-no-yu or Tea, as it developed during this period is a key element. Buke culture, particularly in the area of esoteric or spiritual beliefs and practices, is also important. Having read most of the available writing about wabi in English, I have the impression that it is an important but slippery idea. In contemporary usage, wabi is often confused or conflated with sabi and is now a trendy term, wabi-sabi. What is meant now by wabi-sabi I think is different from the 16th Century Japanese usage of wabi. One must be aware that the history of tea has developed many layers over 450 years, so something of an archaeological approach is needed to separate out what was happening by time period. Many confuse later developments in the philosophy of tea with earlier practice. Many descriptions of wabi and wabi-sabi in the current marketplace of ideas are vague and contradictory, and are often co-opted in an effort to sell something, such as interior design. The typical descriptions in English have an over-emphasis on appearance, and vaguely dance around how something has the look of, or symbolizes, “humility”, “melancholy,” imperfection”, “impermanence”, or “insufficiency” to list a few commonly used words. Wabi is sometimes described as a style or a characteristic, but, 16th Century Japanese wabi was really Buddhism, which is a practice, rather than appearance or posing, and in order to understand it, it is useful to examine the larger social implications in 16th century Japan and how it was applied culturally. In my view, wabi (at the time) was a Buddhist Way of Being, and was primarily an ethic rather than an an aesthetic, although it had aesthetic impacts. This ethic of wabi informed the Tea Master’s material choices, and we can see that in the design of their tea houses, gardens, and utensils. I think examining wabi as an ethic makes it easier to understand wabi aesthetic choices and provides a deeper and richer meaning and context. Old Japanese words that are more specific to study in terms of wabi are wabicha (poverty tea) and wabizumai (the wabi way of living). These words imply that wabi was something one practiced, rather than what something looked or felt like. Ethically, the question is why was this wabi method of tea developed, and, what for? The prominent people in the wabicha movement such as Jo-o, Sogyu, Sokyu and Rikyu were dedicated and accomplished Buddhists. All of them were in business as Tea utensil dealers and teachers of esoteric Tea ritual. They created an inclusive tea (Soan Tea and later, Wabi Tea) as a Buddhist Culture of Awakening within the Machi-shu class. The practice of an art as a Buddhist path to enlightenment or "way" (do or michi) is a well understood application among the Japanese martial arts. Judo, kendo, and kyudo are examples. Recent scholarship on the sociology of wabicha focuses on its ceremonial or ritual function, such as in the work of Theodore Ludwig and Herbert Plutschow. The earlier form of the Tea ceremony, or Shoincha, as practiced primarily by the Ashikaga, used the tea ritual to assert dominance and hierarchy. It had a confirmatory purpose to impose social order. Ludwig and Plutchow make the case that the goal of the Buddhism - oriented wabicha experience was transformatory; to break down the barriers of suspicion and distrust between rivals and to allow them to get to know each other as people. In modern corporate-speak, this was like a “bonding and team building” transformatory experience to promote unity among the Japanese, particularly those of rival clans and different classes. What was valuable to the Tea Masters about the material objects - the construction of the ceremonial space and the choice of utensils - was not their rarity, or importance, or cost, or desirability, but how they harmonized and related together to support this transformatory experience. There is a similar sense of these wabi - Buddhist values that we see in some sword fittings, especially tsuba. What wabi tea innovated was a commonly understood visual language to to express wabi ideals. This visual language was applied to many aspects of Japanese material culture and indicated an accomplishment of cultural refinement and taste. So, yes, read more books if you want to understand how wabi aesthetic language relates to sword fittings. Here are some suggestions. Japanese Art and the Tea Ceremony Rediscovering Rikyu Japanese Tea Culture Cha-No-Yu Turning Point Tea in Japan A short introduction to a Japanese martial art (and other arts) as a Buddhist Way, is Zen in the Art of Archery by Eugen Herrigel. On the topic of Buddhism, and its views on materialism and the proper way of living, I find the works of Stephen Batchelor to be helpful. Tim Evans

-

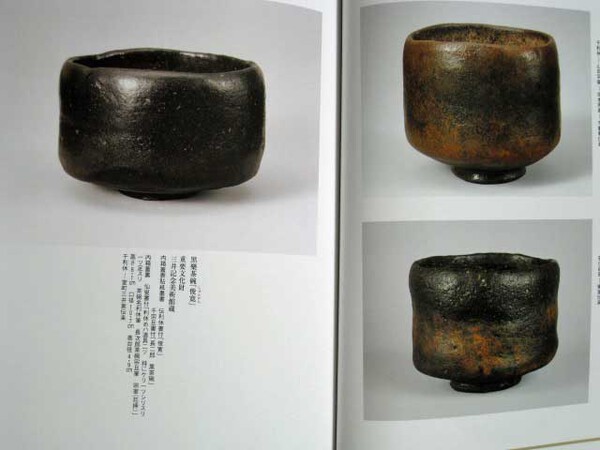

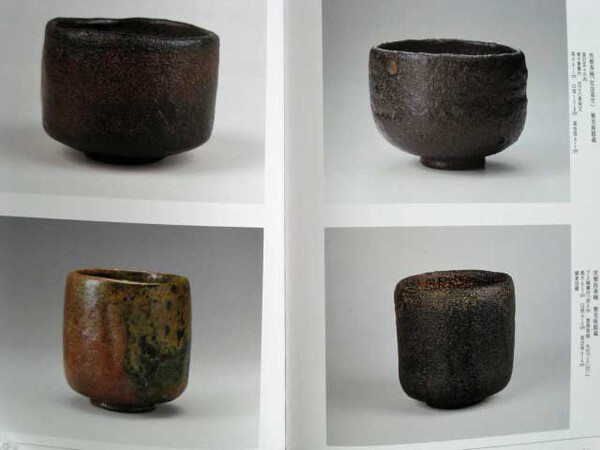

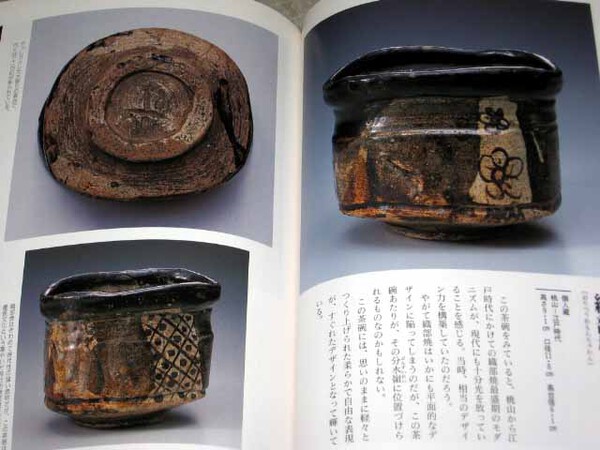

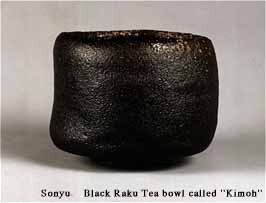

Here are some examples of important masterwork tea wares that show similarities to YKB and other Momoyama - Early Edo period tsubako such as Nobuie and Hoan. It is thought the pottery came first, and was developed as a unique aesthetic style that complemented and reinforced the intense experience of the Soan, Wabi, and Daimyo forms of cha-no-yu. The practice of cha-no-yu went 'viral', as we say today, in the Momoyama period, and was embraced by all classes of Japanese. Read about the great Kitano tea gathering for example. Because Buddhism was of vital interest to both the Tea Master and the Warrior, it is not surprising that the unique visual language developed for cha-no-yu crossed over into tsuba.

-

Hi Steve, You had mentioned above learning about Momoyama and Early Edo Buke culture and specifically their practice of Cha-no-Yu, so I thought I would offer up a bit of a book list. Rediscovering Rikyu: https://books.google.com/books/about/Rediscovering_Rikyu_and_the_Beginnings_o.html?id=vkqBAAAAMAAJ Japanese Tea Culture: https://books.google.com/books/about/Japanese_Tea_Culture.html?id=VmTqCB9TBXYC Turning Point: Oribe and the Arts of Sixteenth-century Japan: https://books.google.com/books/about/Turning_Point.html?id=q50bU2oPj98C Tea in Japan: https://books.google.com/books/about/Tea_in_Japan.html?id=O8MjO6U62xgC Japanese Tea Ceremony: https://books.google.com/books/about/Japanese_Tea_Ceremony.html?id=pS_RAgAAQBAJ These last two are probably the best overview titles. Some of these are out of print, so your local library might be able to find a copy. >My belief is that one cannot properly appreciate or understand Yamakichibei guards unless one also studies the culture of Tea in the late-16th and early-17th centuries.<

-

Thanks for the compliment. I have been experimenting lately with the scanner and thought the images were good enough for posting.

-

-

-

-

-

Thanks Brian, An interesting signature variation that needs more research. I agree with Bob Haynes that some of the tsuba signed this way are very good and have some age to them, and so are worthy of study.

-