-

Posts

719 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

13

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Posts posted by GRC

-

-

That's an interesting observation John.

Unfortunately, I just have images of the oshigata so I can't say one way or the other... sorry

-

-

Congrats

Looking forward to what comes next

-

And another Nanban variant:

-

3

3

-

-

-

Sorry Dale, but I have to add this info about the mei on the underside of the lid:

You probably couldn't tell from the seller's images I posted, but the lids on these kettles are typically made of copper, so it would be very easy to carve into.

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

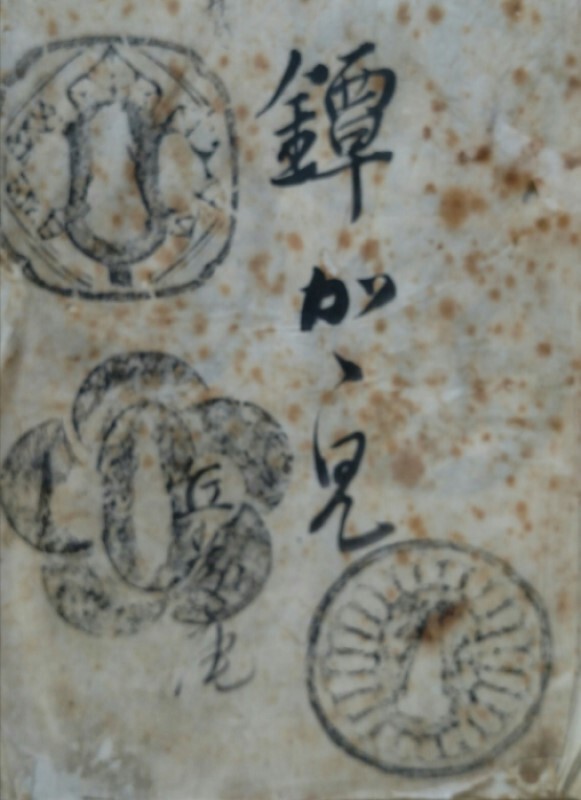

At the very least, it would give us a date range for that specific "type" of cast tsuba... Edo, Meiji, or both, it is what it is.

There's a ton of this "type" of tsuba, with a bunch of different motifs, but they all share the same easily identifiable characteristics.

So, it wouldn't be difficult to make the leap and assume with a fair degree of confidence that all the ones of this "type" would have been produced by this, or similar groups of kettle makers.

-

2

2

-

1

1

-

-

Funny Brian...

,and here it is without the kettle...

The one on the kettle has the identical pattern to the ura side of these cast tsuba:

Here's the omote side:

-

3

3

-

1

1

-

-

-

-

Nice one Vitaly

blossoms for sure, snowflakes have a different look compared to those sukashi.

Here's a little sample of the range snowflakes can take (from simplest to most complex):

and the radial Amida yasuri rays were done by lots of schools (this one is certainly not by Yamakichibei though).

Vitaly, I suspect your tsuba would likely get "binned" in with the Tosho or Katchushi as you suggested with your "early Edo armorer" attribution.

Love the decorative sekigane "plugs" in the hitsu-ana.

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

yup that was a nice one... sad I missed it

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

well that settles that then

Thanks Steve.

-

Hi Andrew,

The gold nunome work is definitely done by "Hizen"... the dragon chasing the sacred "tama" jewel, as well as the silver nunome scroll-work "karakusa pattern" on the seppa-dai (that is mostly rubbed off now).

And that chiseled X shape formed by what looks like a crossed ribbon is a "kamon" or family crest.

Someone posted the same kamon from a print source earlier this year I think... can't remember the thread or who identified it though... it may have been @Bugyotsuji (Piers)?

The plate shape and thickness looks more like a Shoami piece though...

Aizu Shoami made this shape the most.

I can't say that I've seen any Hizen work on this shape tsuba before... or at least it's not triggering any memories of specific examples

I guess those Egyptians were getting creative!

All in all, it's definitely not your typical combination of features.

It's possible that someone back in the day, had a Shoami tsuba and sent it off to be "dressed up" by some nunome workers from Hizen... maybe just keeping up with changing fashions and trends?

-

1

1

-

-

Perhaps this one is from the same producer?Cast, plus fukurin.Also, I noticed, the guy's head fell off (bottom left, just under the hitsu-ana).

-

1

1

-

-

@Spartancrest, good question,

And @Bugyotsuji, nice bit of research to fill us in with

The whole topic of "what arrived when, and how" in Japan is very interesting, especially given their early exposure to Westerners in the mid-1500s, followed by the long period of isolationism of the Edo period (other than the few Portuguese trade-ships that were allowed to port each year, and their trade with China and the Mainland).

-

2

2

-

-

If it is a painter's name, then it's possible that the tsubako was re-creating one of the painter's works and credited "Tessai" by putting his name on the tsuba.

I recently posted some info about the Jakushi school (totally unrelated to this tsuba) who did that (at least once) with their "bamboo blown in the wind" themed tsuba. So, it shows that "citing a painter's work" has been done before on tsuba.

Just food for thought...

-

I think Piers has it right... looks like Japanese "shibazakura" or "moss Phlox" to me too:

A travel site had this to say about a shiba-zakura festival:

"There are multiple spots in Japan that are famous for moss phlox but we, the editing team recommends Fuji Motosuko Resort (Fuji kawaguchi-ko town, Yamanashi prefecture). Here, you can admire Mt. Fuji and moss phlox that spread wide like a carpet at the same time. In the park, an event known as “Fuji Shibazakura Festival ” is held when moss phlox are in peak. This year in 2017, the event will be held between April 15th and May 28th."

-

1

1

-

-

22 hours ago, ROKUJURO said:

in larger numbers as souvenirs for Western tourists.

Hi Jean,

I have to point out that there's still no evidence to support that... or at least none has been presented to date on this forum.

Which experts have made that conclusion and what evidence was that based upon?

Mass production of Shi-iremono was in full swing by the mid-1700s, so mass production was originally intended for the Japanese market.

Also note:

I'm not at all implying that this particular tsuba was made then, nor am I passing judgement on who it was made for.

I'm merely commenting on that above statement that came across as a "statement of fact" rather than the opinion expressed by some or other author at some point... who still seems to be unnamed.

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

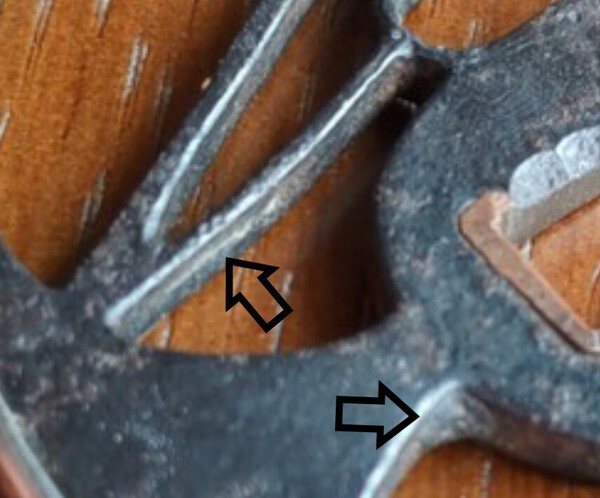

Hi Vitaly,I'm leaning toward cast copy (99% certain)... but sometimes images can give the wrong impression though.I'm guessing the fukurin was probably added to:1- dress it up a little and make it look more "fancy", and...2- maybe hide some casting flaws on the outside of the mimi (because the inside of the mimi also looks pretty messy in one area... so maybe there are more flaws elsewhere)In the zoomed-in image below, it looks like there's a clear mid-line seam along the thin sukashi, and the "inside corner" of the sukashi at the bottom right looks too "globby", rough and irregular to have been done by a chisel.There are other areas that show a hint of a mid-line seam but they are darker and less focused....and this part is too messy... looks like all of it is best explained by casting flaws (rather than corrosion of some kind).All the "bevels" along the majority of the sukashi edges also makes me think this was cast.... and of course, this is all just my opinion.

-

2

2

-

1

1

-

-

soft metal copy of one of the Kinai ones:

-

1

1

-

-

I anticipate a bidding war...

-

3

3

-

-

cool, thanks Jean

I hear you on the longevity aspect... never an easy task.

-

Sorry @Brian, not trying to start an argument at all, but just wanted to point out how "loaded" your recent post was.

It is filled with ad hoc hypotheses: a hypothesis added to a theory in order to save it from being falsified.

These are merely statements of opinion, which means an opposing opinion could be generated just as easily.

These are just tools of rhetorical persuasion (once again),

and sadly, one view or the other will most likely reinforce the views of those who have already taken their position on the subject. Otherwise, the more persuasively stated opinion, or the opinion that is stated most often, will likely win over anyone who is new to the topic.

Both opposing views are essentially useless, because they are just "banter".

So once again, the debate strays from the use of evidence.

...or worse, using the perceived absence of evidence to falsely justify a hypothesis.

Here are some counter points... just to point out how easy it is to do:

8 hours ago, Brian said:So are you saying this vast industry existed, and because they were not seen as great items, they were just ignored for hundreds of years and by tens of thousands of scholars?

I would argue that is just as plausible a statement as saying "there is no book on it, therefore they don't exist".

But neither can be confirmed, so why keep going with it?

Rhetorical question (a question asked in order to create a dramatic effect or to make a point rather than to get an answer):

Why would anyone focus on writing a book on these lowly mass-produced objects, that would have most likely been made (if at all) for the consumption by commoners, not samurai? They're not hand-made, just hand finished, so they fall way down on the scale of craftsmanship and in a completely different industry.

It would be almost as worthy as writing a book on McDonald's plastic happy meal toys... except that is tied to modern pop-culture, which people are obsessed with, so there probably is a book on those, ugh...

Or in a Japanese context, why not write a book about who made wooden rulers in the Edo period? Pointless...

Fact:

We also know for a fact that there are next to no surviving records and very few archeological items for the entire iron casting industry.

Rhetorical question:

So where would the records be for someone to research and write a book about them?

Fact:

Almost every cast-iron tsuba out there with some "apparent age" is either wakisashi or tanto sized.

Hypothesis:

I think it would be easy to conclude (if they were indeed made in large numbers during the Edo period) that most of these were intended for the commoners who could not wear a long sword.

Rhetorical question:

If these were only made for Westerners and export post-Edo, then why not make them all the "more desirable" katana size? The makers & sellers would have made a lot more money.

In my experience, only the ones that are being made now, with a high degree of accuracy to an original, are of katana size. These ones are deliberately being sold to deceive the buyer... buyer beware!

Fact:

I would also like to point out, Brian (among several others), that you are conveniently ignoring all the published scholars (listed many times now) who have stated the existence of cast-iron tsuba during the Edo period as a matter of fact.

You are merely "choosing" which "expert" to follow.

Both are irrelevant (for the most part), because these expert opinions are only as good as their source material.

So far, only Sesko has provided a reference to Japanese records about kettle-makers producing cast-iron tsuba in the mid-1700s, that could be considered even remotely close to "valid". But even that would need more supporting evidence to be considered "proof".

Fact check for Brian:

"tens of thousands of scholars?"... that sounds like a massive exaggeration.

A few hundred maybe...?

Fact:

These writers were all trying to research and show "the best of the best", handmade objects, to celebrate the amazing craftsmanship of the Japanese tsubako.

Rhetorical question and observation:

Why include mass-produced objects that employ almost none of the skills and techniques of the tsubako, and were made by a separate industry?

...and again, with next to no available information, especially considering (if I recall correctly) from the Japanese review article I cited earlier in the thread, that the majority of the excavations of casting sites took place in recent decades.

So there was almost a complete absence of information cast-iron production and facilities, at the time that most research was being done about tsuba.

Here's another massively flawed ad hoc hypothesis:

9 hours ago, Brian said:Most of the references that have been found so far are easily explained by a handful of hobbyist artisans maybe playing with something. Most of it is explained by the writers simply not having enough knowledge of what is wrought iron, what cast means exactly etc.

What proof do you have that the writers were confused each and every time they wrote about the materials a tsuba was made of?

That assumption is just a convenient way of dismissing any statement that doesn't agree with your position.

It is true that the naming of different types of metal alloys went through some shifts, especially in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but you can't use those transitions in terminology to just brush away every single statement that you don't like.

Likewise people can't just dismiss Joly's assessments of what was a cast tsuba in the collections he published information about in the early 1900s. None of us were there, nor saw what he saw, so we can neither dismiss it nor take it as absolute proof.

At face value, Joly's observations are just as valid as any other tsuba scholar, but again, are not an absolute proof.

@Brian I don't recall if you partook in that endeavor, but several people have done that, so I'm calling it out.

People are just choosing to follow the expert who agrees with them while trying to discredit the expert who doesn't.

SUMMARY:

Facts vs hypotheses...

Hypotheses only serve to direct the avenue of questioning.

Hypotheses cannot be used as factual statements to justify a belief.

Unfortunately, we're currently at an impasse due to a lack of concrete evidence to support either position.

I will leave you all with two facts that have been unearthed through this thread:

1- The iron casting industry had "industrialized" to a large extent starting in the early 1700s, and was no longer dependent on small scale, individual medieval-type tatara.

2- There was an increased demand for tsuba starting in the mid-1700s. That includes "mass-production" of tsuba (material composition not specified), and shi-iremono ("ready-made" tsuba... materials not specified).

And now I leave you with one last Rhetorical question:

Given both of those facts, why wouldn't the cast-iron workers "get in on the action" and profit by producing something that there was demand for?

ie. more tsuba of a decorative nature, that were not intended for battle of any kind.

I haven't seen a single logical explanation to justify why these craftsmen would just sit idly by on the sidelines when they could also be profiting by selling these objects.

And of course one could make the argument that cast-iron tsuba were too lowly an object for the Japanese "bushi" of the time... but in my opinion, that just doesn't hold any weight if you consider production for the commoner (if that actually happened).

But that's just another hypothetical question, and not any kind of proof at all.

On that note, I am taking Steve's advice and moving on to other topics, but won't hesitate to call out people's BS on this topic whenever it comes up again (as I'm sure it will).

Hopefully some magical evidence will be unearthed some day that ends this debate one way or the other.

And although my interpretation of the evidence gathered so far has me leaning more to one side of the debate, I really don't care which way it goes.

Everyone is free to have an opinion... just be mindful of trying not to state it as a fact.

Evidence is evidence, and that's all that matters.

As Steve rightly pointed out,

All we know for certain, is that no certain conclusion can be made at this time.

Thanks everyone, it's been interesting

, and I have enjoyed "wasting my time" with all of you

, and I have enjoyed "wasting my time" with all of you

Sorry @Steve Waszak, had to poke a little fun at that.

And thanks for the kind words earlier... I will try my best to live up to them (although it seems like a daunting task).

-

7

7

-

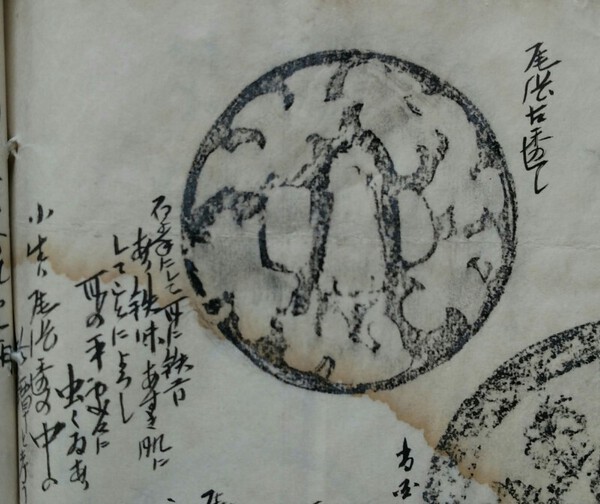

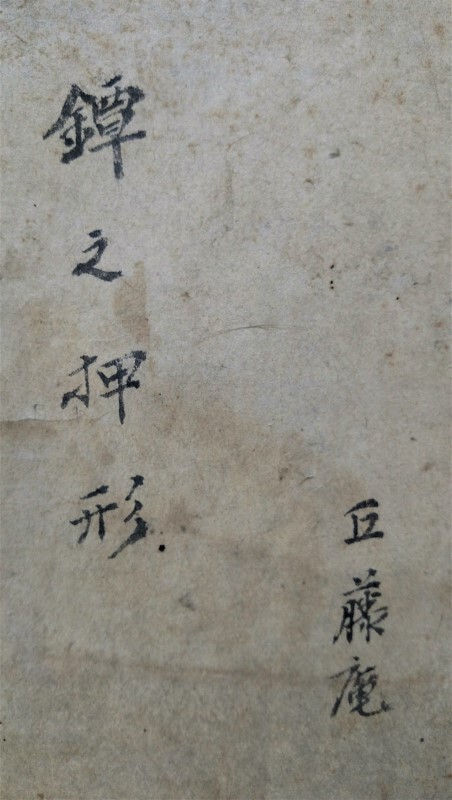

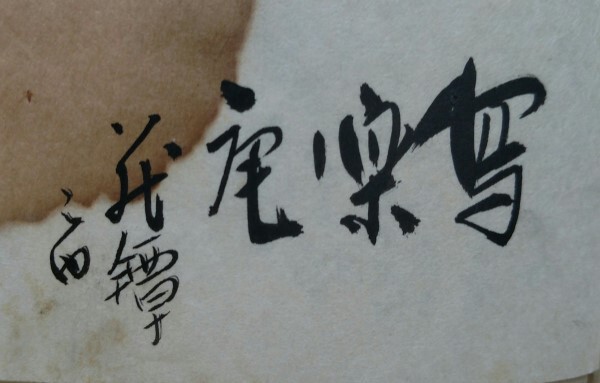

Tsuba Oshigata translation help requested - inkbrush script

in Translation Assistance

Posted

Thanks Jean,

The owner of the oshigata thought "Owari" was in there too, so I had already put that in the name of the image files

Brian, waves are a possibility.

However the typical tsuba wave motif has more of a curl and a rounded "bulb" at the tip of each wave.

I know of some later Ukiyoe woodblock prints that have waves with pointed tips, but you don't see that in the waves of sukashi tsuba (or at least I can't remember seeing any specific examples).

I suspect the motif on this one is probably intended to be flames, with one set of flames moving inward from the mimi, and another set moving outward from the seppa-dai.

Here's some flames from a Japanese depiction of a demon with a flaming sword:

Flames from a dragon's mouth, or flames around the sacred "tama" jewel are common motifs, but an entire tsuba of just flames is really rare.

Regardless of whether these are flames or waves, the tsubako and/or patron who commissioned it was definitely not conforming to the "expected" and was probably trying to make a statement with this one.

It grabbed my attention the second I saw it, and it's one of my favorites.

I'm hoping someone will eventually come through with a translation of all the script... keeping my fingers crossed

Maybe I should say, I'll keep a candle "burning" in anticipation?