-

Posts

594 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

11

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Posts posted by GRC

-

-

Hi Robert.

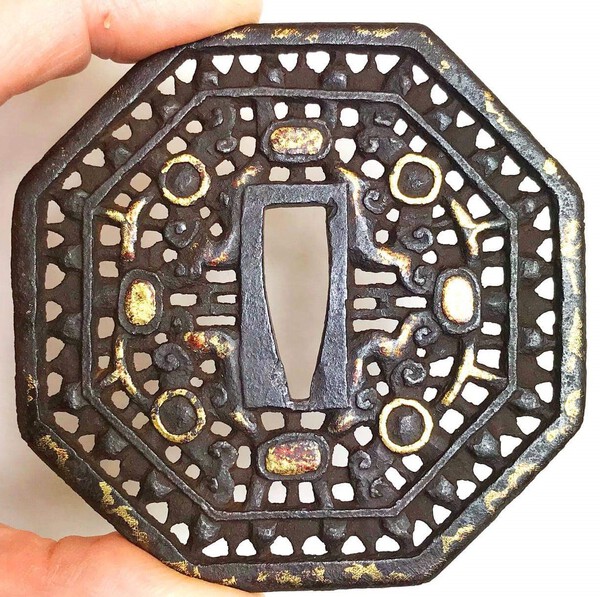

The motif is a drying rack for sea cucumber (not tuna).

The motif was popular during the Edo period and was a symbol of prosperity.

The tsuba looks like it has a one piece construction to me. (either carved then corroded in some areas, or more likely, it was cast and has multiple areas where "casting voids" can be seen and there are two "crevice-like" casting "splits" on the surface of the top cross-bar.

If what you are calling the "fill areas" have a different color (it's harder to tell with the lighting of the images), maybe they have a surface layer of silver overlay that has tarnished over time to have a more greyish look.

-

1

1

-

-

Geraint, there seem to be a lot of older references to "Heianjo sukashi" but no one seems to be identifying them as such these days.

Frankly, I don't know what these look like or what their range of sukashi styles were.

So I bet there are lots of older sukashi tsuba that are just being named as some other school, but they were actually produced by the Heianjo school.

It's almost as though the label was too difficult to apply so it was just abandoned at some point

and John, Onin can be separated into two categories of inlay: one that has the ten-zogan dots, with or without some simple outlined sukashi elements, OR the category that looks much more like the Heianjo style of inlay.

Varshavsky has some great examples on his site: Ōnin tsuba | Varshavsky Collection

Although, as you point out, the Onin never seemed to do the ultra-realistic inlays like that insect.

-

2

2

-

-

-

Those are very nice Tobias

-

1

1

-

-

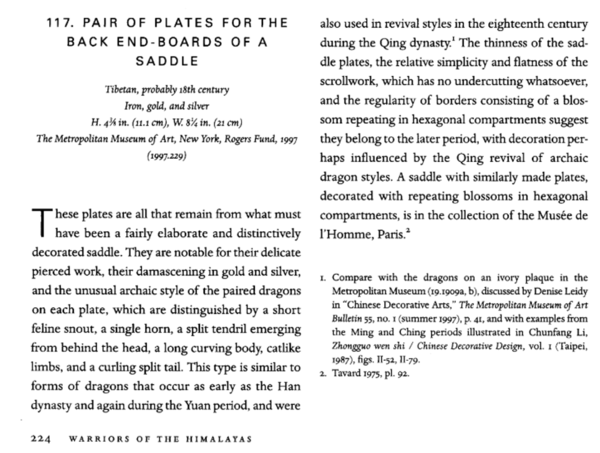

By the way, I did a bit of digging myself and found these Tibetan comparisons at the Met Museum...

Here's a decorative horse saddle plate from Tibet that is in the Met Museum, and it has the same dragons that are on some of the tsuba I posted as being continental (although I should have stated "most likely" or "probably" because I can't be 100% certain... I let my own brain turn it into a statement rather than a likelihood):

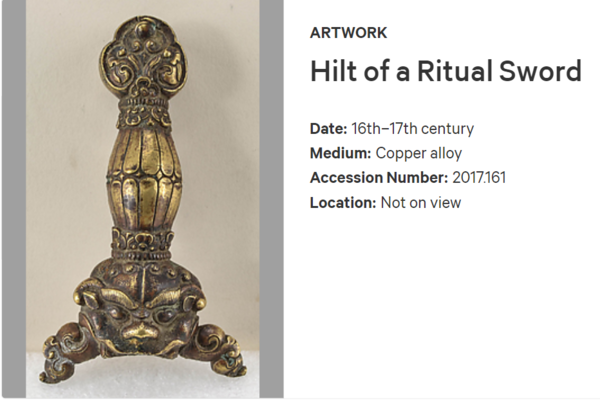

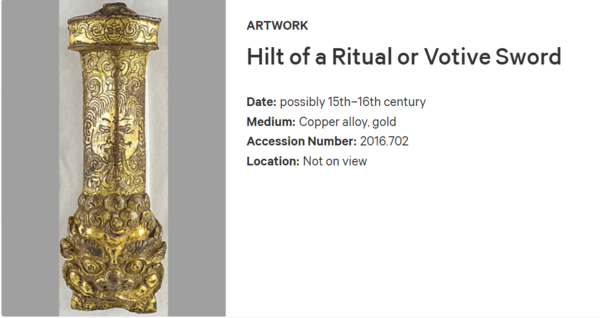

And, the mask that is on the guard on the left looks a lot like these earlier 15th-17th Century Tibetan mask-shaped sword guards in Met Museum:

So everything about these is saying Tibetan (every aspect of the motifs, the seppa-dai shapes, the sukashi is drilled or simply carved with no undercutting, the nunome on the 2nd one is done with Chinese-style cross-hatching), so it makes it far more likely that these were one of the following:

1-made on the continent for use on the continent (but ended up in Japan at some point where the nakago-ana was modified)

2-made on the continent but intended for export (Asian export guard)

3-made by a Chinese smith living in Japan (Nagasaki area had a large community of such smiths and artisans)

I have a hard time seeing how these could have been made by a Japanese smith (although again, it is possible, but it seems like a pretty slim chance).

-

3

3

-

-

Kiril, I agree with your key points, especially that evidence is the key and opinion doesn't matter until it is supported by evidence.

As far as I know, McElhinney is writing a book about nanban and asian export tsuba, with some collaboration with Peter Dekker.

He has already published several articles on the matter and is actively researching the subject.

I'm not aware of his methods or examples that he is basing his statements off of, but I respect that he is attempting to sort out the details (with research) that the NBTHK is so sorely neglecting with regards to their categorization of "nanban" tsuba.

My impression of his efforts is that they are based on evidence, and that he is trying to correct the standard "opinions" that already exist among the Japanese nihonto group because they are built with heavy bias and have many flaws (especially in the nanban category).

You are 100% correct that an "expert" is only as good as their evidence.

The danger is always when ego enters into the picture and some people allow their own legitimate expertise to cloud their judgement and allow them to turn some of their suppositions into statements of fact.

I think that's why many people seem to have a certain disdain for experts these days...

However, my impression of McElhinney's posts on his facebook thread on the subject, is that he is not closed-minded and recognizes where some guards have influences from many areas and cultures, making it nearly impossible to pin down a point of origin. With other guards like these Chinese-styled ones, he seems fairly certain and often makes reference to having, or having seen, a base of comparison.

At a certain point, you still have to trust that actively researching experts, for the most part, are genuinely trying to their best to research a topic and present the best possible conclusions. The whole point of research is to build a better understanding and to continue to refine or restructure their conclusions over time, as new evidence comes to light.

I would make the case that, as you pointed out, it is possible that some of these Chinese-looking guards were made as direct copies in Japan, but I would suggest that there is more weight on the side that suggests the guards were made on the continent:

1-It is very difficult to find examples that have not been mangled and altered to fit a Japanese blade, as almost every example on YahooJ has had hitsu-ana added is such a way that it butchers the original design.

2-Almost every example has had a much longer and larger nakago-ana cut into the seppa-dai (usually going in the opposite direction to fit a katana rather than a slung Chinese sword).

So let me float these questions:

1-Why would the Japanese make a faithful copy of a Chinese or continental motif, including a Chinese style tapered rectangular seppa-dai that does not fit an ovoid Japanese koshirae?

2-Why make a nakago-ana that would then need to be altered to have the opposite orientation and have a point and a blunt end to fit a katana, rather than having two blunt ends like a Chinese style hushou guard that is meant to be worn, slung from the hip?

3-Where is the evidence that the Japanese were making direct copies of Chinese and continental sword guards? It seems that in almost every Japanese form of artistry, they took the initial influences from other cultures and then immediately made it "their own" by doing it in their own style.

Making exact copies of another culture's work would seem to be a departure from the norm for the Japanese.

So in my mind, there are multiple reasons to think the guards were made on the continent, vs only the thought that they could have been made in Japan (although it is still a possibility!).

Personally, I'm going to favor "made on the continent" unless better evidence comes along, but I will always keep an open mind.

And, as you point out Kiril, I would also like to see the comparisons McElhinney is using to justify the dates that he is proposing.

Regardless, I think it's great that these ideas and questions are being floated and discussed, because the entire nanban category is in dire need of more research.

-

2

2

-

1

1

-

-

On 1/26/2022 at 5:08 AM, JohnTo said:

Markus Sesko has a small reference to cast iron tsuba in his book the Japanese toso-kinko Schools (p 129) which states that the kinko artist Daininchi Fucho (active around Horeki, 1751-1764) learned his skills ‘from Ugai Gorozaemon who belonged to an Osaka-based family of kettle casters who produced cast-iron tsuba as a sideline.’

I just wanted to add a second quote to help validate the above quote from Markus Sesko:

specifically, that Japanese kettle makers were producing cast iron tsuba as far back as pre-1750.

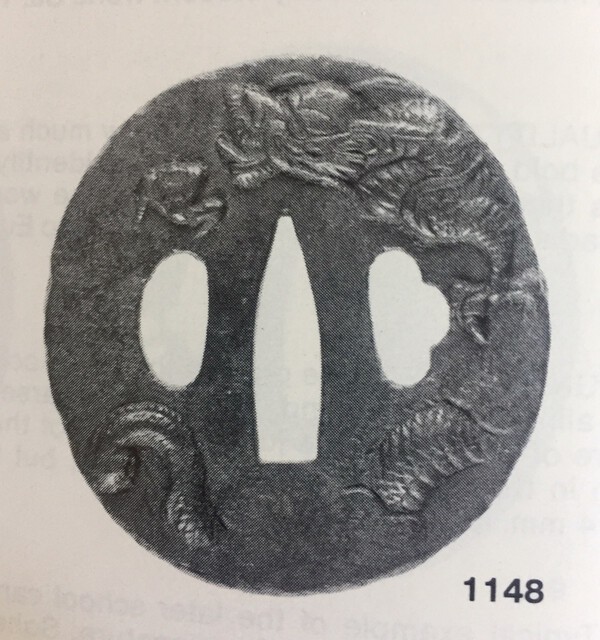

This time it's from Haynes catalogue #4, item #1148:

I have seen multiple examples of this tsuba, sometimes in iron, sometimes in bronze, with varying degrees of detail in the dragon's relief and the surface texturing of the plate.

Some of them are signed with a mei, some with a kao, but most are mumei.

I even saw a Japanese seller openly describe one example as "cast-iron, but then carefully worked by hand".

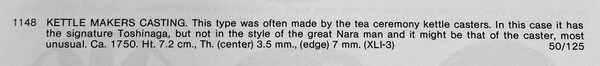

I also saw another one posted for sale with this statement (later translated to english):

So both Sesko and Haynes, have research that supports cast iron tsuba production to at least the early 1700s.

Given all the information that was dug up and researched in this thread, It seems like we need to start looking at some of the cast iron tsuba (and other fittings) in a new light, and recognize that many examples that most of us were previously dismissing as modern era (post-Edo) productions, were actually produced in Japan at a much earlier date.

The hardest part will be trying to sort out which were Edo period and which were Meiji or later... nightmare... maybe close to impossible in many cases.

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

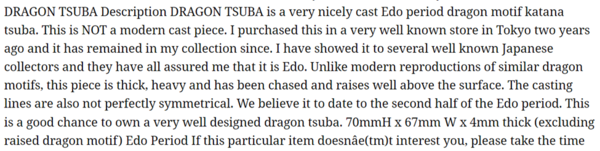

Ok two great quotes to follow in two separate posts:

This first one was spotted by Dale Raisbeck (Spartancrest),the seemingly infinite source of old writings about Japanese artistry and craftsmanship, and endless source of tsuba comparisons from just about every museum collection on the planet

The quote comes from the 1895 Kyoto Industrial Exhibition.

Although this is POST-Edo and NOT directly connected to tsuba, it does show that the Japanese were specialists in modifying cast-iron products into softer workable wrought-iron that could be elaborately chiseled and worked by hand after they were cast.

This strongly implies that the technique was well known to the Japanese and that they must have been using it for quite some time, in order for them to have achieved this level of proficiency by 1895.

This now elevates this idea from a mere "possibility" or even a "probability", to a statement of fact.

Here is the full quote about one of the metal workers whose works were selected for the exhibit. with the most pertinent section in bold:

QUOTE 1 from F. Brinkley:

"JOMI YEISUKE.

This artist stands easily at the head of the bronze manufacturers of Kyoto, and indeed has few peers anywhere in Japan. His pieces, having designs in relief formed of silver, gold, shakudo, shibuichi & so forth on a glowing golden ground, show the perfection of work in bronzes. There is hardly any colour that he cannot produce with certainty, though some, of course, present greater difficulties than others. The celebrated lobster-red, unattainable in Europe and declared by foreign writers to be an accidental result in Japan, is no accident in Jomi's factory. Most remarkable, perhaps, is the process that this artist has developed of manufacturing bronze so as to be entirely proof against climatic influences. As an example, the visitor need only look at the balcony of Jomi's show-room which, though it has been exposed for years to sunshine, rain, and frost, retains its lustrous, rich- coloured surface as perfect as when it was first placed in position.

In his factory one may also see a tour de force peculiar to Japanese workers in metal, namely, the conversion of the surface of cast iron into wrought iron, by which means it becomes possible to chisel elaborate designs at comparatively small cost upon common household utensils.

Jomi has 95 medals of gold or silver and certificates of merit obtained at various exhibitions, domestic and foreign."

Incidentally, there is also a great little intro to the "metal workers" section that discusses how the sword fittings artisans were busy reinventing themselves and figuring out what they would produce in the post-Edo Meiji era.

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

Hi Kiril,

The Chinese attributions for the first four images were done by dedicated collectors of Chinese weapons and fittings, who also commented (with some noticeable "judgement", that these were wrongly described as Japanese nanban tsuba, as it was their opinion that these were clearly Chinese made).

I would agree with you that the first three eventually ended up in Japan because of the modified nakago-ana that come to a "V" point.

However the fourth one looks completely unmodified, made in China for a Chinese blade that was slung from the hip with the cutting edge down, and never modified to fit a katana:

I would also point out two disctinctly Chinese (or more broadly "Sino-Tibetan" features:

1- The outer rim design with two parallel boarder rings, containing a ring of lotus petals. So far, I have only seen modifications of this outer rim decoration on known Japanese tsuba, and they never have the lotus petals specifically, always something "more Japanese" in its styling.

2- The tapered rectangular box seppa-dai.

Furthermore, the lack of hitsu-ana on these four tsuba, produced at a time when hitsu-ana of some type were on nearly every Japanese tsuba, also points to the notion that these tsuba were never intended to go to Japan (even though three of them got there eventually).

I'm going to quote McElhinney from "Asian Export sword guards and Nanban tsuba" on Facebook, because I agree wholeheartedly with the sentiment:

"If a guard looks Chinese in every way, and it cannot be proved to be Japanese, then we must assume that it is Chinese."

The middle set of three images certainly could have been made in Japan, but I can can't yet say for certain (either way).

My suggestion of a continental origin stems from the distinctly non-Japanese style dragons on two of the tsuba, which are more South-East Asian.

And, the one with the large circle around the seppa-dai, is a feature that is more commonly found in southern Chinese, Vietnamese, or possibly Korean guards, although the inner tapered rectangular seppa-dai (within the circle) is more Chinese or possibly Vietnamese.

Kiril, do you have any details you can share about why you think any one of the first 7 tsuba shown might be Japanese copies of Chinese guards?

I'm definitely interested in hearing your views.

-

2

2

-

-

Spotted a few great examples of unaltered nanban:

These ones were all described as Chinese Hushou (tsuba), dated from the Qing Dynasty 1650-1700:

Not sure of the date on these ones, but they are also made outside Japan, somewhere on the continent (not just China)

Note the first one has purposeful, original hitsu-ana, so it was likely made for export to Japan:

These ones are definitely Japanese, also with purposeful hitsu-ana (mid to late Edo, post-1750 :

-

2

2

-

-

10 hours ago, roger dundas said:

Not a criticism but just for my edification, is 7.63 x 7.31 considered small for a tsuba?

Maybe borderline between katana and wakizashi size ?

Just for clarification.

Roger j

Roger, here's my 2 cents on this question:

I was just reading in one of Haynes' catalogues, that the size of the tsuba on a blade had no consistent dimensions (or at least throughout the Momoyama and early Edo periods...I assume it became more regimented when the Daisho became mandatory in the early Edo period).

Otherwise, tsuba size changed widely over different periods and localities, and different samurai favored different sizes to suit their needs.

Haynes also pointed out that the size of tsuba had no consistent relation to the size of the blade, so to get a better sense of what was fitted to what, just look at the size of the nakago-ana.

In general, I think 7.6cm would fall in that cross-over area you mentioned (smaller-katana sized tsuba, or larger-wakizashi sized tsuba), but this of course gets further complicated by the average sizes of tsuba produced by different schools at different times.

I don't know the average sizes of Onin and Heianjo tsuba off the top of my head.

Personally, I don't really care how big the tsuba is.

A great tsuba is a great tsuba, no matter how small...

-

4

4

-

1

1

-

-

Stylistically, the arrangement of inlays looks more like Onin to me...

Here are some known Momoyama period Onin examples for comparison:

Note 1: the first four have a similar hitsu outline treatment as Luca's

Note2: Onin often used a brass outline around the seppa-dai, whereas Heianjo did that a lot less frequently. Also note that most of the ones below have traces of "rope" patterning, rather than being perfectly smooth (closeup view in the last pic).

Note3: same surface texture of the plate between Luca's and the ones below

Note4: the flower treatments in Luca's tsuba look more like the Onin flowers below (the leftmost tsuba in the 1st and 2nd row))

-

The first one definitely looks like a rimbo/rinpo/rinpou 輪宝it, and it looks like the ends of the spokes are either jewels (which are often seen in these wheel motifs, like in the image below), or maybe even the tips of vajra (a handheld scepter with Buddhist symbolism).

The rinpo is a Buddhist symbol shaped like a wheel with eight spokes (usually 8). The eight spokes represent the Buddhist "eighfold path" to reach enlightenment (don't ask me what the eight steps are though)

-

-

-

Pong anyone?

The ball is moving so fast it's looking a little stretched out

-

2

2

-

-

I'm with Grev on that one, it's one of the fiercer looking, more naturalistic tsuba tigers

-

Shachi fuchi & kashira set, signed:

-

2

2

-

-

I picked up this tsuba a while back, partly because the construction seemed so bizarre.

The sukashi flower motif is one solid piece with the seppa-dai, but it is wedged in and pressure-fitted inside a completely separate mimi.

I've got a few questions:

1- How common was this, and does anyone else have any other examples?

2- Who made tsuba like this and WHY?

I can't figure out the advantage (if any) of making a tsuba this way.

The only thing that popped into my head was that maybe someone went to the trouble of replacing a previously damaged mimi that was original to the one-piece construction of the tsuba?

There are images of a similarly built tsuba (#121) in the Nakamura tsuba book. It is shown whole, as well as disassembled:

I suspect tsuba #120 is as well (shown below). The tips of the sukashi elements don't sit flush with the surface of the mimi and they all appear to be a little too "crisp" where they meet up with inner surface of the mimi.

Also, I suspect the mimi was hit with a punch 3 times (roughly at the 10 o'clock position) in order to make a tighter compression fit to hold onto the tips of the iris flower... kind of like tagane-ato positioned along the mimi instead of around the nakago-ana.

Could someone be so kind as to translate the captions for tsuba 120-121?

Many thanks in advance

-

1

1

-

-

Richard, you peaked my curiosity...

Love that tsuba too btw

Interestingly, I found a scholarly article on the dendritic growth of silver, and it happens in the presence of sulfate ions (S04 with a 2- charge)... that's a sulfur atom combined with 4 oxygen atoms, which will interact with the silver ions in such a way as to allow for the silver to travel/grow in a dendritic pattern (similar to the branches of a tree, or branching neurons in the brain, or "fractal" patterns in general).

So here is one possible explanation for what we're seeing on that tsuba:

Some of the captured sulfur in the silver tarnish would have to have reacted with some source of oxygen to become sulfate ions. (not too sure how readily this occurs in the environment of a tsuba's surface during feudal Japan

, but let's assume it happens)

, but let's assume it happens)

Then throw in the presence of some moisture for the silver and sulfate ions to interact in solution, then voila, you will get dendritic growth of silver.

(remember that there are some silver and sulfur ions present in the tarnish, which will dissolve in water, even though the tarnish is mostly a covalently bonded network solid that will mostly not dissolve in water)

The image below shows lumpy/clumpy growth of silver in the presence of nitrates (nitrogen with 3 oxygens), but dendritic growth in the presence of low concentrations of sulfates (sulfur and 4 oxygens).

This growth occurred on a sheet of copper in this experiment, but I imagine it would be similar on some other metal (like an iron tsuba).

Here's the link to the article if anyone else is interested:

Video of the dendritic growth (looks like a whole coral reef is growing, but it's silver):

https://doi.org/10.1021/jp201484r

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

2

2

-

-

Hi Mark.

I assumed your use of "sulphate" was accidental

Just wanted to clear it up for other members.

Just wanted to clear it up for other members.

As for solubility,

2 hours ago, mas4t0 said:While the solubility is low enough to classify Ag2S as insoluble, it is not truly 100% insoluble (in the binary sense). This is also of course assuming pure water.

I completely agree, and wasn't disputing that at all.

As for weight vs mass,

Once again, I completely agree that they are different terms with different meanings.

"Mass", as you say, is certainly the correct term to use.

I chose to use the word "weight" because that was the word most people were using in their posts, and what they would typically use when speaking to other people, so at the time, I didn't think it was necessary to add another layer of nuance to the scientific terminology being used.In hindsight, I probably should have included "mass" in my statements.

Again, this illustrates the omnipresent issues with discussing scientific or technical concepts in a chat or forum-post type of format.

Ultimately, my goal in posting was to try to bridge the gap between academic science and a "layman's" understanding, where perhaps the last bit of science training someone had was back when they were in high school

Dirk,

thanks for posting the closeup pic

The spread and rise of the tarnished silver are both clear in that photo.

-

2

2

-

-

Geoffrey, "gimei" are tsuba that have had signatures put on them on them that basically make the claim that they were made by a particular smith or "school" of smiths.

Gimei signatures could have been added at the time the tsuba was produced, or added later by someone who likely wasn't even a tsuba maker, both having the ultimate intent of inflating their value for sale purposes.

These were/are very common practices in Japan (and elsewhere).

I think what people might be suggesting by saying "late productions" is that these are all likely genuine Edo period tsuba, but are later direct "copies of", or simply "in the style of" earlier works.

During the Edo period, there seems to have been a fair number of tsuba workshops that made large quantities of certain tsuba styles and motifs.

Although most were made by relatively skilled craftsmen, there's still an element of "production for the masses".

It's also possible that some of your tsuba were made by a particular tsuba "school", where apprentice smiths were making "copies" of a master-smith's work in order to scale up production. These wouldn't be considered "gimei" but would be considered "school work".

In the end, these things are worth what people are willing to pay for them.

But on that note, a well made copy or well made "in the style of" tsuba still has intrinsic value because someone will like it and will want to have it.

The difference in the end will be a value $30-$50, a few $100 to a $1000, or many $1000s...

From my observations, the closer the connection to the original master smith in both time and location of production, the higher price people are willing to pay for it.

Something like this type of ranking:

1-original master work by a master artist

2-original work (but maybe not a "masterpiece") by a master artist

3-work in the style of the master, by one of their direct students (early school work)

4-work in the style of the "school", by a later generation smith working in the school (later school work)

5-some tsuba artist/craftsman somewhere, with no specific connection to the original master or school, who produces a piece in the style of a particular school ("gimei" if signed with some specific school or earlier smith's name)

...

...

x-mass productions made by casting or machining. (* I didn't want to give this one a number so I called it "X". We've seen many examples where someone ended up paying way too much for one of these. The newly made ones are really deceptive!)

I may have missed some in that list... so anyone can feel free to add to it, or muck around with the idea

I suppose you could also make the case to re-rank #2-5 based on the specific talents of the respective smiths who made the tsuba

Geoffrey, I'm guessing most of your collection would fall in the #4-5 categories, but I'm most familiar with only one of yours, so I leave the rest to the other NMB members to offer up their thoughts.

I just wanted to help with the idea of "gimei", then I got caught up in values and rankings...

-

2

2

-

2

2

-

-

That's an interesting difference to point out Ford...

The formation of a network would definitely "rearrange and reorganize" the existing silver atoms into this new network with the sulfur.

So why does it stick better to silver than to iron?

Here's my hypothesis:

I could see the silver nunome sliding around more on an iron surface because it was merely "applied" to the iron surface to begin with, so it was never really "integrated" into the iron in any atomic sense. The atoms in the steel below would all be "metallically bonded" to each other so it might be harder for a newly forming network of silver sulfide to "push" its way down into the steel, so it would preferentially "skate" over surface as it grows.

Take the "path of least resistance" so to speak.

Conversely, the tarnish buildup on a chunk of silver would actually be "pulling" silver atoms that were actually "metallically bonded" with (and among) the other silver atoms of the block, so maybe the network forms in such a way that it is more "integrated" and woven into the silver block itself. Maybe even forming "peaks" and "troughs" going in and out of the silver block, kind of "locking it in" to a certain degree, rather than the "loose sheet" that seems to form on iron.

This is just some deductive reasoning on my part... so I'm not sure if these statements are actually true

But, it could help explain why the tarnished silver nunome on iron comes off so easily, but the silver tarnish is harder to remove from a silver base.

-

2

2

-

-

Congrats!

I applaud your thrift store rescue, and then your seeking out of information

.thumb.jpg.a433554467a07b8e323737d4ff0943e5.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.5c0f3eadde70ee8cf43ac7c4b259ee1d.jpg)

Tsuba construction

in Tosogu

Posted

I sent this image to Robert and he asked me to post it.

Here are the areas that caught my attention as evidence for being cast.

Some areas, viewed on their own, could be viewed as old corrosion that had been completely removed at some point, leaving a pitted area.

But, thinking about all the highlighted areas as a group, it seems to add up that this tsuba was initially cast then finished by hand to remove any raised casting seams (leaving only the sunken casting flaws) and adding the silver surface treatment (if it is a silver overlay).

It's also possible (probable?) that the triangular punch marks that texture the lower areas, were done by hand as well.

Regardless of how it was made, this is a nice example of the namako (sea cucumber) drying rack motif