-

Posts

815 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

1

Everything posted by docliss

-

Brian, I believe that ‘the odd little faces’ that you describe have their origin in taotie. These zoomorphic heads are a recurrent theme in Chinese art, dating back to the early Shang period (1600-1050 BC), and are a further confirmation of the strong Chinese influence upon this sub-group of tsuba. They are described as being characterised by a pair of eyes; a wide central ridge representing a nose; an upper jaw; and two front paws. The brow commonly has two domes, and may possess a pair of horns. That such features may have, in some instances, been later modified to mimic the imagined features of Westerners is not improbable. John L.

-

To return to the enigma of the ‘N’ on Brian’s tsuba, while it is true that there were only six chambers comprising the Dutch East India Company, as listed above, there have been discussions regarding the authenticity of a seventh flag bearing the VOC cypher, with a ‘C’ above it – the so-called Cape Chamber flag. This misunderstanding appears to have arisen as a result of the custom of the VOC to use its logo, together with the initial of the local base or office, on crockery, silverware and headed notepaper used in that area. Is it possible that the ‘N’ on Brian’s tsuba was used in this way to represent the area of Nagasaki? John L.

-

I am intrigued by the ‘N’ on Brian’s tsuba. Frequently the VOC logo of the Dutch East India Company was accompanied by a letter representing one of the six chambers. Thus: A represents Amsterdam D Delft E Enkhuizen H Hoorn M or MZ Zeeland (in Middelberg) and R Rotterdam. But I do not know what the ‘N’ represents, and have never before seen a chamber letter on a tsuba. John L.

-

Greetings, Peter. I have always supposed that the VOC logo features on many auriculate tsuba for two possible reasons. Either, when present as a kebori logo and hidden by the seppa when mounted, as an indication of the tsuba’s manufacture by that company or, as a decorative element, which must have been ubiquitous in Japan at the time and place of the production of such tsuba. That it featured as a decoration on tsuba made specifically for a bearer associated with the Dutch East India Company is, indeed, a third possibility. As to whether the VOC logo is incorporated into the beautiful karakusa-moyō work beneath the taotie on your tsuba is an impossible question to answer definitively. Personally, I suspect that it is present merely in the eye of the beholder. John L.

-

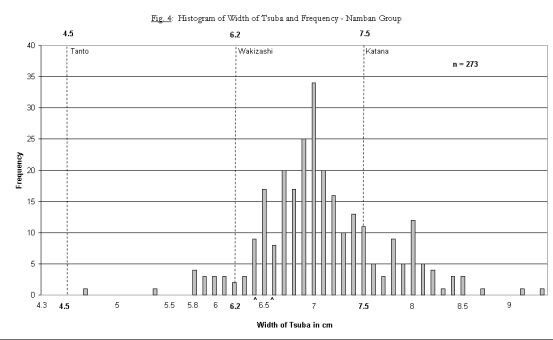

Jim, my personal conviction – although not universally shared - is that one of the defining characteristics of the Namban group is the presence of undercutting, so I would hesitate to include your latest acquisition under this heading. But, if submitted to shinsa, it would certainly be labelled as such. I am attaching two histograms illustrating the height/frequency and width/frequency of 273 tsuba of the Namban group, taken from The Namban Group of Japanese Sword Guards: a Reappraisal. John L.

-

Christian, Jim’s tsuba, featuring affrontés dragons with a tama jewel, while quite skilfully carved, features virtually no true undercutting, with the openings in the plate being simple holes through it. The ryō-hitsu are probably later modifications, and the shakudō fukurin is an unusual feature. I would suppose that this guard, which I personally would describe as an openwork guard with a very strong Namban influence, to be of the late 18th or early 19th centuries. John L.

-

Dear Jim In answer to your question regarding the maximum size of Namban tsuba, I can inform you that of a random group of 273 such tsuba the commonest height and width were 7.3 and 7.0 cm respectively. There were 4 tsuba measuring more than 8.8 cm in height, and 45 measuring more than 7.7 in width. I can supply these numbers in detail if you wish, but there were 5 tsuba measuring between 8.8 and 9.2 cm in height, and 6 measuring between 8.5 and 9.2 cm in width. I apologise for the errors in my original posting. Kind regards, John L.

-

Attached are images of another heavy, cast bronze tsuba of the late Kagamichi type which, like John’s, is inscribed YAMATO (NO)JU IETSUGU SAKU. Presumably this is by H 01841.0, working in Yamato in the 1700s. It is ex the Jepson and Tassell collections, measuring 8.1 – 8.1 cm. Interestingly, there is a similar, signed guard shown as # 530 on p.166 of the Illustrated Catalogues of Tokyo National Museum: Sword Guard. John L.

-

Matt’s chidori/wave tsuba is not Omori work; the depiction of the waves and of the gold spray are both quite unlike that found on the work of that school. Also,the sukashi and the form of the mimi are not in character, as he correctly suggests. I can only surmise a C19, Mito attribution, and wonder if the mimi is actually a fukurin? John L.

-

Colin, thank you for your enquiries. There are, indeed, sekigane both at the top and bottom of the nakago-hitsu, and these are of dark copper. My reasons for (tentatively) attributing this tsuba to the Ko-Shōami school are as follows: • the shape, size and thickness are all appropriate for that group; • the katchūshi type plate, with its coarse tempering; • the tsuba’s obvious age; • the absence of any mei; • the positive silhouette openwork; • and the koban-gata seppadai. But I may well be guilty of looking for features which would confirm my attribution, but could equally well apply to another. John L.

-

The attached thread illustrates many good examples of Hikone-bori work. Attached is another example, possibly by a Tetsugendo artist. John L.

-

Dear Chuck I believe that one of the problems we encounter when trying to appreciate tsuba of the Sōten school is the fact that they comprise such a mixed bag of work. For this reason I prefer to label them as ‘Hikone-bori work’, rather than to attribute them to a specific school. Hikone-bori includes work by a wide selection of artists, ranging from the rarely encountered work by the two, mainline Sōten maters; through the 20 or more artists of the school, of whom Nomura Kanenori I and Kitagawa Munehide are the outstanding ones; the Hiragiya school in Kyōto; the Tetsugendō school, also based in Kyōto; down to the numerous poor copies made by the Aizu Shōami artists in the late Edo period, as shiiremono for sale at the docks of Yokohama. The majority of the Hikone-bori work that we see is examples of the latter, and we should not allow these to cloud our judgement of the scarcely seen, better work of this group. John L.

-

I have attached below an image of a small, openwork tsuba of black sand-iron, depicting a chrysanthemum blossom and vegetation in positive silhouette. It is tate-maru-gata, measuring 6.6 cm – 6.2 cm – 0.5 cm. The blossom, in the upper segment of the guard, has its petals detailed in low relief, and the leaves, in the lower segment, have kebori detail. There is a single kozuka-hitsu, and the worn nakago-hitsu, in a koban-gata seppadai, has dark copper sekigane. There are numerous tekkotsu in the mimi. Do the members agree with my attribution of this work as being Ko-Shōami of the Momoyama period? John L.

-

Steve, attached are the two images that you requested; I am not sure that they show the detail you require. John L.

-

Ian's observation regarding the extensive wear to the bottom one third of the plate is clearly relevant, as is the comparable wear to the inlay in the same area. If this inlay was a later modification to the plate, as some of you suggest, it has obviously been there long time, and was presumably added before the wear on the plate became apparent. John L.

-

Yes please, Ford, I would very much like to see the images that you offered. I think that the impression of cross-hatching that is seen in my enlarged image is due to pixellation, and is not apparent when the tsuba is examined 'in hand'. Thank you for your helpful comments. John L.

-

Ford and Curran, certainly food for thought, but I don't think that the grey zogan is silver, and am fairly certain that it is not nunome - in spite of the very hard nature of the plate there are no visible, residual cross-hatchings to be seen anywhere. If you are both correct it does, of course, simplify the whole question. John L.

-

The attached image is of a mumei, sawari-zōgan, ita-tsuba from my collection. Rendered in a hard, darkly patinated iron, migaki-ji and mokkō-gata, it measures 7.5 – 7.3 cm, and is extremely thin, being only 0.2 cm at the centre, and 0.1 cm at the edge. Three engraved grooves form a circle surrounding the ryō- and nakago-hitsu, and a similar, single groove outlines the mimi. The decoration is limited to the defined area between these grooves, and consists of four cartouche-like quadrants which contain cloud formations rendered in gold and sawari hira-zōgan; the irregular surface of this inlay suggests that the gold, as well as the sawari, was melted into pre-formed recesses in the plate. There are two elongated ryō-hitsu, and the nakago-hitsu contains dark copper sekigane. The inlaid decoration on the reverse is similar in concept, but is very sparse. Presumably, this tsuba should be considered to be Hazama work, but it differs in many respects from the majority of the work produced by the Kunitomo family. Certainly the iron quality is appropriate for a family that had its origin as gunsmiths, and the migaki-ji, produced by a process that necessitated the filing of the alloy to produce a smooth surface, level with the plate, is also characteristic of the work of this ha. But the thinness of the plate contrasts with the description of ‘average Edo age thickness’, and the design of Hazama tsuba is described as being of two styles – either large, pictorial areas of sawari inlay covering the majority of the plate, or fine, linear designs covering only a portion - quite unlike the design here. Any comments will be gratefully received, John L.

-

A very interesting thread; I have never been personally impressed by the 'butterfly' interpretation. But how do we name this image in a Japanese form? John L.

-

I should like to acknowledge all of those members who contibuted to this thread. As is usual, all of my queries have been answered very satisfactorily. Thank you. John L.

-

Pete, I believe that the two final kanji may be read as either 'DONIN' or 'DOJIN' - am I correct in this? But the third and fourth kanji still have me puzzled. John L.

-

Can any kind member please help me with this translation? On p.225 of Tsuba: an Aesthetric Study the kanji 二子屋満仼則祏道人 are translated as FUTAGOYAMA (NO)JU NORISUKE DOJIN. But I feel that this is erroneous, and am puzzled by the third and fourth kanji. With thanks for your help, John L.

-

My grateful thanks to all the members who provided such heplful replies to my queries. I remain slightly puzzled by the fact that the artist should include such comprehensive date details without adding his own mei. And I should still love to hear more details about the Maria Ouspenskaya collection from Pete Klein .... John L.

-

The Russian film actress? Her bio makes no reference to any Japanese collection - please tell me more. John L.