-

Posts

732 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

1

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by kaigunair

-

Ah, excellent idea mariusz! Thanks.

-

Anyone seen a rose depicted in tosogu, or can post a pic of what would be the traditional form of a rose in Japanese early edo art? I'm hazarding a guess that the image of a rose in Edo period Japan doesn't resemble the same type of FTD "dozen red roses" we normally associate with Valentines day here in the West. The examples I'm looking at make me think they can easily resemble botan flowers: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosa_multiflora http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosa_rugosa Any pointers towards reference books or ideas on how to go about looking up how a rose might have been depicted in Edo Japan would be much appreciated. (FYI, This line of research does not have anything to do with a late V-day gift or an "I'm Sorry" gesture for the Mrs!) Thanks in advance.

-

I know its a bit delayed in terms of "internet time", but was gathering the thoughts to address some good points + life events have kept me away. I agree that what we consider early tosho or katsushi tsuba should be considered more "dogu" or utilitarian things that art. However, at some point in time, we'd have to agree that tsuba moved from being dogu, a necessary piece of the sword, to a particular item where the wearer could signal his tastes and education, his "breeding" if you will. I would submit this happened during the late muromachi and took off in the momoyama period. Later on, tsuba were made as export items as well as items made solely as gifts that were not to be mounted. By breaking up tsuba into discreet and distinct groups, we could more easily move from the generalizations and onto the task of forming a deeper understanding and agreement of the various aesthetics and values inherent in various tsuba. This would be in contrast to just trying to place them into the "schools". So to start, I would propose that the "naturalist-ness" of a muromachi or earlier tosho tsuba is much different from a kanayama or higo tsuba from the momoyama period. Its interesting that chawan, the Japanese tea bowl, has been mentioned, because it would be a very easy connection to make between the aesthetics of chawan and the tsuba of the same period. As an example, the most famous tea bowl from korea mentioned, the Kizaemon Ido, may be a perfect proxy for some of the conflicts I am finding with tsuba history and understanding. There is the "official" history of the bowl, which, in summary, is that it is a common korean rice bowl that just so happens to have the magical wabi and sabi combinations that make it oh-so-perfect. Then come are the nagging questions. First off, its name, the Kizaemon Ido, is the family name of the merchant who first owned it...and what good salesman doesn't have a good story to accompany a piece. Second, if this is a common rice bowl, where are all the other similarly designed rice bowls in korea? I do believe that only recently there has been findings which confirm it is a bowl from korea, but given all the other detritus from dig sites and research into korean pottery, we would assume such common rice bowls should pop up a whole lot more. Thirdly, the current research and consensus is that Japanese merchants directed ceramic production in countries such as China and the South Seas, importing these designed "art" wares into Japan, to sell to their wealthy or up-and-coming clients, who used them for the tea ceremony, meaning these were, in fact, all designed, art pieces. So wouldn't a more plausible history of the Kizaemon Ido be that Japanese merchants also placed orders with Korean potters, and that the Kizaemon Ido was a built to order chawan? So this esteemed chawan, far from being a common, everyday item, may in fact be an "art" piece, ordered and built to specs reflecting the tea aesthetics of the time, to be sold by a wealth merchant in his salon to a wealthy patron engaged in the very business and political oriented world of tea during the momoyama era. What's most interesting is that since the 1980's, research into Japanese ceramics with tea bowls in particular, has blown away the traditional understandings of their histories which were passed down since the 17th and 18th centuries, affecting such esteemed tea bowl "schools" such as raku and seto and oribe-ware. Basically hard archeology via kilns and the stores these wares were sold in has shown that a great deal of what had been "known" about chawan is actually the result of astute marketing, while the truth is much more complex, fascinating and interesting. But returning to tsuba, in the same way, we seem conditioned to look at a pre-Edo, momoyama period tetsu tsuba, and think of the designs as "simple" or from the hands of less-skilled artists of the momoyama era vs those of the late Edo period. I know I did. But as I tried to show in the photos, in really really good tetsu examples, what we might first see as simplistic and quaint designs should actually be very high-brow abstract, even avant-garde type art design, occurring in 16th century Japan! It would also be a bit unfair to compare the aesthetics of late edo kinko tsuba to momoyama tetsu tsuba. However, when we compare Edo-period tetsu tsuba to Momoyama tsuba designs while holding the connection between momoyama tsuba to the same abstract and avant-garde designs of the chawan during that time, that is a good start at building a basis for judging and comparing the aesthetic qualities of tetsu tsuba. As a last example comparison with chawan, it is said that in regards to oribe-ware (which is more linked to a style than to a particular kiln or "school"), there is a definite dichotomy between the aesthetics of momoyama era wares and those of Edo, the former being bold and strong while the latter, perhaps being more "technically competent", lacking the same energy and vibrancy. If a similar parallel be can made with tetsu tsuba designs between the two periods, then perhaps there are other similarities between where the understanding of chawan was up until the 1980 and where we are with tsuba understanding today...

-

Hi James, count me in. Hope you're able to bring a few pieces to this year's show too.

-

returning to the topic at hand, it would appear that what one might consider "crudeness" on the part of pre-edo tetsu tsuba, may in fact have been a conscious on behalf of the tsuba makers, and, even more importantly, reflected the wishes of those patrons who ordered these pieces. We know from studies of tachi mounts, temple bells, and bronze mirrors that the craftsmanship existed in 17th century Japan to make more realistic "late edo/meji" like pieces. So wouldn't it be very important to determine why such pieces weren't demanded? (there is probably a strong connection to the earlier quote about mimesis vs allusion). At the same time, moving into the early to mid to late edo, we know that the rise of the merchant class had a profound effect on the arts of Japan. If we can distinguish between the differences in values and their corresponding effect over what constituted "beauty" by this group vs the momoyama bushi, it would go a long way towards shaping our study and understanding of what we could consider "objective" qualities of beauty held by each of the two very distinct groups. Now whether we personally like one set of objective standards vs another, that is definitely a separate discussion.

-

and especially in ceramics, we see that there is a very deliberate attempt at less "perfection" and more natural abstraction as time progresses: (If it isn't obvious, I have tried to place all pictures in the previous 3 posts in chronological order...)

-

-

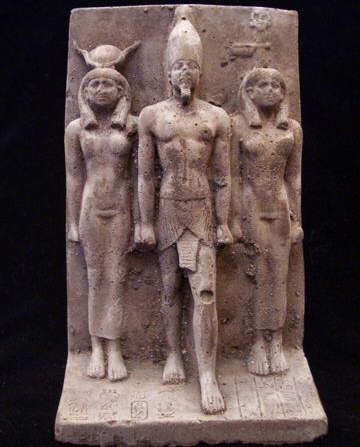

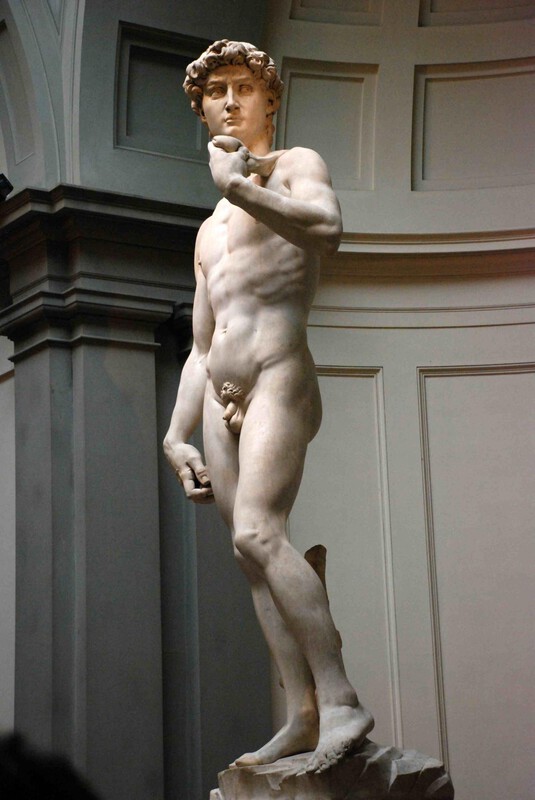

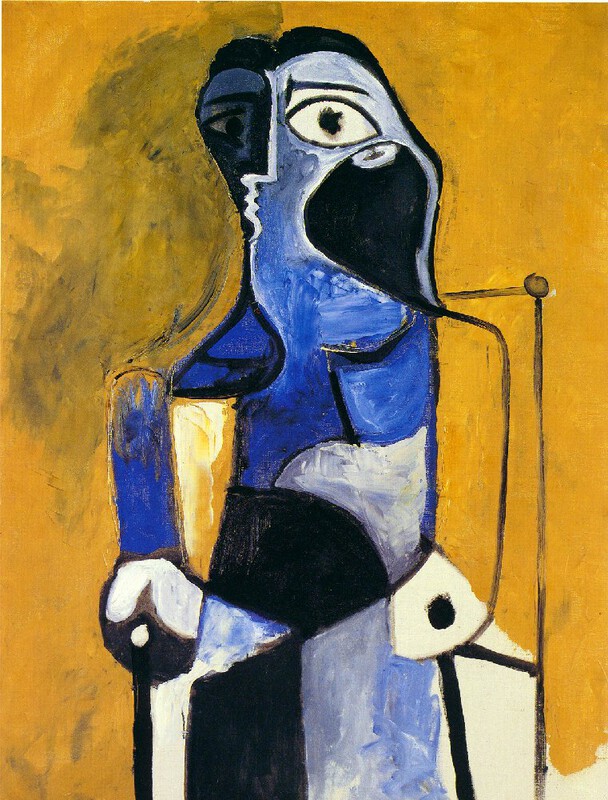

Taking examples from other art genres, and argument could be made that the "simple" technical qualities of many tsuba were done deliberately, not because more advance techniques did not exist, but because of the feeling or message the maker wished to evoke. For example:

-

Your most insightful comment yet. Let's see if you are a man of your word. Chris, I have had similar thoughts about early pre-edo tsuba. Basically, the current body of knowledge dates and classifies in a manner akin to some sort of evolutionary scale, somewhat like the following: or But its interesting you brought up Japanese ceramics in your post.....

-

Rich, I'm getting a warning when I try to follow your link that there is possibly a virus attached to that page...?

-

I thought there was something interesting about this tsuba too. I've begun to notice more examples that have this curly brass inlay, and more interesting is that there seem to be examples of the base plate with and without the brass, with varying degrees of brass inlay. Traditionally these would probably fall under some sub classification of the heianjo school, but when combined with the non-brass examples, might indicate that these were sort of template tsuba that could be customized with none, some, or more brass inlay depending upon the whims/finances of the customer. This example would fall into the "more brass" category as opposed to those in the "some brass" having more open surface, sometimes with brass dots in addition to a lighter apply of the inlay. I am at a loss at as to what the brass' design is supposed to represent....maybe a garden path or worm eaten paths (often seen along the mimi/rim), or possible some fabric texture when shown on the face? They have an older feel to me, but at the same time, I am bother by the lines as in the examples I've seen, they are often not sharply cut out- yet the use of somewhat expensive brass material in such a tsuba is puzzling. The hitsuana normally don't fit the standard designs normally accepted for edo period dating. If earlier that later, I'd guess these were some type of regional workshop piece. Perhaps a yet-to-be documented fad genre, like akasaka in Edo, or a precursor to the Kyoto gift tsubas. Maybe someone is doing more research on this genre of tsuba and is snapping up examples?

-

Hi Steve, I am definitely not the person to answer this question, for so many reasons! That's why I was asking the questions . But, as an example of what I'm coming across online using search terms like "is art appreciation subjective or objective" , here's a online course outline on art appreciation: https://learn.canvas.net/courses/24/pages with some examples in the section "M5": https://learn.canvas.net/courses/24/pages/m5-how-we-see-objective-and-subjective-means In trying to relocate that info, I stumbled across an interesting article on Flemmish art. Though only able to briefly scan through it, it does seem there are many parallels between where the understanding of Flemmish art/artists was and where tsuba study is, and how a deep connoisseurship of a few helped to unlock understanding and appreciation on a vast majority of under appreciated works.... http://www.columbia.edu/cu/arthistory/faculty/Freedberg/Why-Connoisseurship-Matters.pdf

-

I would go further and state that in cases of good, better, and best pieces, for the best and most exquisite pieces of tsuba, good art must contain good craftsmanship. Conversely, good craftsmanship may not necessarily result in good art. A point of the previously quoted author is that often craft and art were more closely intertwined in the historical Japan. Think kimonos, tea bowls, swords. Good craftsmanship was necessary to product good utilitarian objects, and pieces considered good art contained good craftsmanship. Yet many pieces exhibiting good craftsmanship did not necessarily rise to good art. Tsuba are both utilitarian and very personal expressions of art. The current method of studying tsuba seems very focused on tsuba-as-craft, mainly looking at construction techniques, the craftsmanship - this is further reinforced by the focus to place a particular piece into a school based on....yes, construction techniques. Wouldn't it be great to develop a set of tools to evaluate the artistic merit of tsuba? Wait, I know what many are about to say: art evaluation is all subjective. Its a very normal, gut instinct reaction, especially during this day and age. But any quick research into art appreciation or art connoisseurship comes up with a large body of writings and course work that discuss how to objectively analyze a piece. The point of such objective analysis is to discern and classify why a piece may be better or best. And after doing so, one can then then make a "more informed" and entirely subjective opinion regarding whether he like the piece itself or not. As food for thought: Mona Lisa, Starry Night, The Thinker, Handle's Messiah. You could say you do not like the piece or wouldn't pay X amount for them. But someone saying that any one of these particular pieces of art is not somewhere in the "best" category would say everything about that person's level of connoisseurship and knowledge and nothing of the piece itself. Its because there are objective criteria in these fields that the art piece is judged against and rises to the top. It would be an interesting exercise to imagine how these same masterpieces would be evaluated if we used the current construct used tsubas, mainly focusing on traits/construction techniques to tell use who created the piece or what school it fits into.....! Good tsuba and best tsuba are going to be judge as such not on their craftsmanship, but because of their artistic rendering of a particular subject/theme and regardless of what school they belong to. Boiling it down to a forum post: What are the objective criteria we currently use to evaluate pre-edo tetsu tsuba, regardless of whether we "like" the particular piece under review?

-

"AESTHETICS IS THAT branch of philosophy defining beauty and the beautiful, how it can be recognized, ascertained, judged... ...There are, however, different criteria at different times in different culture. Many in Asia, for example, do not subscribe to general dichotomies in expressing thought. Japan makes much less of the body/mind, self/group formation, with often marked consequences. Here we would notice that what we could call Japanese aesthetics (in contrast to Western aesthetics) is more concerned with process than with product, with the actual construction of a self than with self-expression... ..Jean de la Bruyére, the French moralist, early in the 17th century defined the quality: 'Entre le bon sens and le bon goût il y a la différence de la cause et son effet.' Between good sense and good taste there is the same difference as between cause and effect.... ...Bruyére's aperçu is, indeed, so sensible that one would expect it to apply just everywhere. It does not, but it does to Japan. As the aesthetician Ueda Makoto has said: 'In premodern Japanese aesthetics, the distance between art and nature was considerably shorter than its Western counterparts.' And the novelist Tanizaki Jun'ichiro has written in that important aesthetic text In Praise of Shadows: 'The quality that we call beauty...must always grow from the realities of life.".... ...Elsewhere - in Europe, even sometimes in China - Nature as guide was there but its role was restricted to mimesis, realistic reproduction. In Japan this was traditionally not enough. It was as though there was an agreement that the nature of Nature could not be presented through literal description. It could only be suggested, and the more subtle the suggestion (think haiku) the more tasteful the work of art. Here Japanese arts and crafts (a division that the premodern Japanese did not themselves observe) imitated the means of nature rather than its results... ...Tanizaki Jun'Ichiro's remark that beauty rises from the realities of life forces us to wonder what these realities consist of." With regards to pre-edo tetsu tsuba, I think the idea that subtleness rather than mimesis is quite universally accepted. It was definitely a chasm I had to cross when making the leap from the late-edo machibori kinko works into early tetsu tsuba. The aspect(s) I have been poking at are more directed at determining how to (and whether to) perceive and value process, and whether it is equally important to understand the environment, the "life" ,or state thereof, present at the time of creation when determining the aesthetic value of a particular piece. I have been enjoying the most thoughtful responses that bring up interesting and valid counterpoints; definitely helps to oil the wheels and clear out cobwebs in the noggin. I imagine this what men once did in the smoking room of those old grand estates. I fear SMS, twitter, and facebook are causing my mind to reject anything thought than 140 characters...and manga has dulled the imaginative impulses of my mind (nod to Guido)....

-

Thanks for the insight again James. Makes sense that your bias for iron dragons would lead you to Echizen. I'm sorry I missed your discussion, but was thinking that perhaps that particular category is enhanced by the sengoku jidai personality and reputation of Uesugi Kenshin, the "Dragon of Echigo". Makes sense if Echigo itself did not produce a prominent tsuba school, and the Echizen school, by that time in the Edo period, was banking on its connection to Echigo via the Esshu province. Or does Shibata Katsuie also have a connection to dragons? Trying to follow my line of thinking, is there a particular type of dragon (rain, fire, or ?) that is most depicted on Echizen tsubas? That would be another interesting link in the history and appreciation of the school....

-

Wasn't thinking nor did I imply anything about fish, but turns out that's somewhat loosely germane to the topic of names/labels/appearances and what they signal: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/corbin-hiar/why-did-one-Japanese-bluf_b_1190704.html In a similar vein, I would think any "serious" Japanese tosogu collector in Japan must have at least one goto school piece, being from the first few generations. men have been living with women for eons, and for eons there has still been a "cultural misunderstanding" between the two. Guido, I definitely would love to spar with you over this topic in person some day. I agree "sweeping generalizations" can be very detrimental to understand, but at the same time, it is also what appears to be used to identify much of the unnamed nihonto and tosogu. But it isn't the same as studying and naming key aspects, the zeitgeists, of a culture's particular values and mindset. In the same way we might say us Americans here hold the value of freedom above all else (with all the multitude of exceptions present in our society, politics and citizens), there are certain cultural aspects of each society, during a particular time in their history, that would be very helpful in understanding their art/craftsmanship/handiwork. Take the 60's here in the states - how far could one develop a connoisseurship for tie dye shirts or music posters or the music itself without an understanding of the culture and times themselves. This could also extend to understanding particular stratas of society - in order to study French art of the late 18th century one would need to know of the Court of Louis XVI; trying to superimpose the ideals and culture of the French serfs/peasantry of this era into the high arts would not lead to a similar understanding. Please excuse those digressions.... Back on topic, it would appear I am, at the least, making 2 underlying assumptions about pre-edo tsuba: 1) The current names/labels we use to classify pre-edo school tsuba into schools have no direct link, whatsoever, to how the bushi at their time of creation purchased their tsubas (i.e. Oda Nobunaga did not ever wake up and say "I'd like a kanayama, or Owari, or Shoami, or Choshu style tsuba on my most recently acquired blade); 2) The current system was solidified in the early-mid 20th Century during a time when Japan was trying to elevate its own arts in the global stage, foster national pride under a back drop of extreme militarism, and was intentionally designed to imitate western forms of taxonomy to give it credence; Then such a system, while making it easy to collect (i.e. I have acquired all the various schools in my collection, or I only collect X or Y schools), would, being fundamentally flawed, naturally create exceptions to the categorizations. The more flawed the categorizations, the more broadly defined some categories must become, out of necessity to fit the increasing number of examples which do not fit the flawed categorizations. This would occur to the point where the categories become so broad and the examples so diverse in traits and characteristics, that even the most novice collector (yes, myself completely included) could accurately attribute items to each category, without ever having any understanding or appreciation of the artistic and creative merits of a piece. Instead, an alternative might look something like this: instead of focusing on dimensions and thicknesses, rim shapes and carving techniques, a discussion about the composition of the entire tsuba, its theme and relative success or failure of execution of that theme, and the signal or statement the overall tsuba would have indicated during the time and place and station it was worn. Then a discussion about the quality of the metal, or use of specific metals or signature techniques could help place the object into the poor, good, better, and best categories. Being the neophyte, I am still formulating such criteria, but I had hoped that there were others with many more years that might share their insights and wisdom gain through years of study. Perhaps an easier question is: what do you consider when determining that a tsuba is a better or best piece?

-

Except for the surface, I like the theme. I see it as the kanji for person on top ("hito" two slanted lines) and possibly the hiragana character "ko" which could be child - a theme of parent a child perhaps? The hitsuana could be stylized temple bells or saddles.

-

A great post James! Getting to the heart of the matter, it doesn't seem the current classification system adequately directs or develops an appropriate appreciation of the aesthetics that were present and valued during the era when these pieces were created. That the current system does such a poor job by design, wouldn't we yearn for a better one? My grievance is that by focusing on the "traits and characteristics" of each labeled "school", our connoisseurship becomes undeveloped or even skewed toward late Edo, Meji period tastes. They would thus also be more "western" than "eastern", more like a course in taxonomy vs appreciation. So, rephrasing the question, would it lead to better appreciation and connoisseurship if we used a different form of classifying tsuba as opposed to the current construction techniques we attribute to the pre-edo "schools"? I have to respectfully disagree. They may not do it in the same manner as we in the west (their "omote" being less outwardly vocal about it), but they do indeed "fuss" over labels, to a great degree, in a way that would shock most westerners who had a window into the thoughts of the "ura". The boom in China of luxury goods is somewhat a more current example, but I'd venture to say it took on deeper and more complicated levels within Japanese society. This also being my own experience growing up in and around kids and families from Japan, in the US, and my own family background...

-

"The Japanese of the 15th century-like those of the 21st and all the centuries in between - delighted in such rules and categorizations. When people gathered and talked about an artistic work the atmosphere perhaps resembled some New York or Paris opening with recently acquired apparel being shown off and much connoisseur-talk about the merits of this or that-whether the pot or the bowl or the ikebana showed the shin of shin or merely the gyo of shin. Still, the emotion called for, the real reason for the party, is familiar. It is the pursuit of beauty. On such occasions, a standard of taste is agreed upon. Good taste is thus a shared discovery that fast shades into a conviction. It may have its origin in the unpeopled world of nature itself but it soon enters proper society... ...Hence, the value of looking back along the long corridors of history and glimpsing a world where beauty was sought, where its qualities could be classified, and where a word for "asthetics" was not necessary.... ....A basic assumption, however, remains. Aesthetic taste, like Miyamoto Musashi's five rings, indicates a method and still something of a hope. Though it does not seem likely, Jean de la Bruyere's dictum yet holds. To enjoy good taste we only have to decide for ourselves what good sense is." I too was prepared for a mob.... Is mere tsuba identification requests the niche most comfortable for this forum? Perhaps what I seek lurks elsewhere in some dark corner of the interweb.... (re: Pete: Ouch! http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capon)

-

For some tsuba, especially signed examples, school identification makes complete sense. But for others, especially pre-Edo tetsu tsuba, have there been other methods of classifying or identifying them? A while ago, I posted a kozuka in shibuishi which could have easily been labeled as "rinsendo" or "kaga". But in actuality, it could have been made by any number of skilled machibori artists of the time. Couldn't the same argument be made of the many unsigned, pre-edo tetsu school tsubas, especially those that seem to have multiple features of many different schools? (the machibori kozuka post is found http://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/13102-rinsendo-shibuishi-kozuka-monsters-ball/?hl=shibuishi) Focusing on pre-edo tetsu tsuba, one argument against this would be that certain qualities in the base metal indicate a particular area of origin, and thus helps identifies to a specific region and then a specific school. This would apply especially to the pre-edo era before the tokugawa began strict control over mining and smelting of metals. But there are many examples of pre-edo tsuba where the base metal does not necessarily match the orthodox description of that school. In these cases, school identification appears based on attributing certain construction techniques and styles to specific schools. If we exclude any mass produced tsubas of the pre-edo age (a topic in itself), would it be correct to attribute muromachi and momoyama tsuba as personal items custom made to a client's taste? Looking at tsuba production as "school" directed would imply that tsuba makers made what they liked, put it up in a shelf or window, and the normal bushi would then buy something off-the-shelf? Tsuba makers would then just make lots of what sold well (we see this more in late work than pre-edo, yes?). In essence, doesn't classification by school then also imply that all tsuba are somewhat shiiremono? But if pre-edo tsuba (both tetsu and kinko) were client-directed, one-off, custom ordered and custom made to a user's specs, these examples would rise above the sea of mass produced works. Such tsubas would more likely represent those examples most admired and sought after and documented in our books. So would it make better sense to categorize these examples by the client whose taste directed them instead of any perceived "school". If not a particular client, then perhaps a particular style or influence of the culture which affected the client's order?

-

Well, this is interesting. Seems like more than a few days worth of posts are missing from this particular thread.... The one I posted that was a few days ago basically thanked James for letting me view his collection of kinai tsuba, and that he has got to write a book on the subject.

-

some additional info which has been relayed to me: -the themes include water wheels, with, along with shippo and kikusui, indicate kyoto. -the kikusui mon would have been kosher in kyoto and momoyama. Oda courted the court, and Hideyoshi himself had basically bought his titles from the imperial family (based in kyoto) so the kikusui wasn't as "non-grata" as I initially thought. Was more shunned by the early tokugawa who were asserting their power over the Imperial court; another reason why they set up their own HQ's in Edo vs Kyoto. So momoyama period kyoto work is supported. Some photos of "similar but different" heianjo tsuba:

-

This tsuba has gone to a friend whose family used an identical mon. FYI, he believes that his family traces its lineage an offshoot of the Taira clan, after they were defeated and scattered. FYIW...

-

Nice pic Steve! Mark, looks like I was incorrect about the kozuka ana...would seem original to the piece given the brass outline of Steve's example. My question now is whether all the spaces in your example would have also been inlayed. At least one void would seem to have held a chrysanthemum on a river (kikusui) This symbol would have represented Kusunoki Masashige (1330's), and would have represented loyalty to the emperor. The kikusui mon really makes me wonder how this plays into a momoyama period dating. The ashikaga would have been in power (1336–1573), after which time was the rise of the Oda-Hideyoshi-Tokugawa era. With a pro-emperor theme, would this indicate a particular region and time? Now I'd really like to know what the motif's mean on both Steve's example and the original tsuba! Here is what the kikusui design might possibly say about the piece (along with current thoughts in tsuba construction and dating): 1) This is a piece contemporary with Masashige, which would mean really early Kamakura. (but this is supposed to be the era of nerikawa and tosho tsuba) 2) This is an nambokucho era period piece, made for someone in the southern court area signaling their protest of the Northern Court. Prior to the rise of the Tokugawa, Masahige would have been persona non grata in the northern court and up until the Edo era. (but the Onin war was later in 1470's, and even at that date, the thought is that brass designs are much simpler) 3) This is a momoyama era piece, based on current thought regarding construction - kikusui theme = ????. 4) This is a post momoyama era (Edo) piece, made after the Tokugawa started promoting neo-confucianism. (construction seems early) A few reasons why my analysis would be completely off: -it turns out the kikusui mon was used continuously after the 1330s. -this is indeed an early plate where the brass was added later. -the two tsuba are not by the same smith. -maybe there is some tinkering needed with the current thoughts of tsuba construction history Interesting or .....