-

Posts

766 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

10

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Hoshi

-

Advice for new collectors from an old dog

Hoshi replied to R_P's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Dear all, A little grace and understanding goes a long way. When I first posted on NMB, years ago, I had purchased a mumei shinshinto blade, a humble beginning. I was greeted in the replies by Darcy who generously spent his time explaining attributions to me, he was graceful in his every words. He could have sneered and said it was a paperweight. After all, he was dealing in Koto masterpieces. There was nothing for him in this sword to appreciate. But he wasn’t dismissive - instead, he saw rightly that this was an entry into the world of Nihonto. Over the years, I came to the conclusion that there is truly no point in lecturing on what “ought to be collected” - the reality is set by the market participants, there is no central planning committee that sets prices. It is all supply and demand. What matters is honesty. Honest description of the items, genuine effort to depict reality as it is. Markets require information to function correctly. Whatever the level one collects at, there is always a bigger fish who - in comparison - will make one’s entire collection fit into the “paperweight” category. Tokubetsu Juyo grandmaster sword? Well, there is a Jubun one that is longer, with a more complete nakago, and a single mekugi ana that belonged to the Emperor. The Jubun collectors can look down on the Tokuju collectors. The Tokuju collectors can look down on the Juyo collectors, and the Juyo collectors can take it out on the Hozon collectors, and so on. Trivially true statement. But there is no point to it. Live and let live, learn and respect others, fight for truth, and don’t fall for delusions. Best, Hoshi- 142 replies

-

- 13

-

-

-

Interested to hear some creative Ideas

Hoshi replied to Nickupero's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Hi Nick, Very interesting case. Were you able to read the obscured kanji? They appear discernible. It is slightly odd that one of the characters overlaps with the cutting test character. If the cutting test was done before, I could imagine it was left as is to indicate "no longer the case" while giving it a certain sabi aesthetics. Like crossing out a name. If it was done after the cutting test, I could imagine that removing it completely was impossible without damaging the precious (and expensive to inlay!) cutting test. A fine mystery. Best, Hoshi -

Looking for the whereabouts of an important Gunto (1000$ bounty)

Hoshi replied to Hoshi's topic in Military Swords of Japan

After reflecting, I believe it is wiser to turn this into a board prize. (if you're feeling 'rugged' by this rule change, started working ardently, and you need the money, shoot me a PM). 1000$ donated to NMB. Thank you so much to everyone who has started to help so far! let's make it a community effort. -

Looking for the whereabouts of an important Gunto (1000$ bounty)

Hoshi replied to Hoshi's topic in Military Swords of Japan

Oh my, thank you! That is wonderful to hear! I must have ended in the spam folder, I will make another attempt. If someone knows...he knows. -

Looking for the whereabouts of an important Gunto (1000$ bounty)

Hoshi replied to Hoshi's topic in Military Swords of Japan

Unfortunately I was just made aware of Jim's obituary by a kind member. https://www.tpwhite.com/obituaries/james-jim-dawson RIP Jim, thank you for your scholarship. In my experience, collectors value discovering new information on their treasured "precious" - precisely what I bring to table. Not to mention, connecting with like-minded and knowledgeable people is always a blessing. -

Looking for the whereabouts of an important Gunto (1000$ bounty)

Hoshi replied to Hoshi's topic in Military Swords of Japan

For information leading to the successful establishment of contact with the current owner. Is Jim Dawson still of this world? I have failed to contact him so far. Hope this helps, - Hoshi -

Hello dear militaria collectors, I am looking to pin down a certain war gunto that has been eluding me to supplement my research. I have decided to try something new. The piece in question was once photographed (owned?) by Jim Dawson, I have not been able to contact him. Back in the days, it was bearing one of his tags: You can find it on Omura's website In every community, there are usually a few elders who just "know where things are" - if someone could be so kind as to ring one of these grey beards to figure this out, I would be incredibly grateful and will issue a generous reward. Here is the automated translation of Omura's relevant section: Has it been repatriated? as in, sold back in Japan - or did the (presumably US-based) owner send it in for papers back in 2011? Any information that leads to establishing successful contact with the owner, I will pay a bounty reward of 1000$. Please be mindful of privacy, and write to me in PM. Who doesn't love a good treasure hunt? Happy hunting! -Hoshi

-

Advice for new collectors from an old dog

Hoshi replied to R_P's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Hello, Failure of knowledge vs Failure of money is a critically useful distinction, thank you @Tsuku for laying it out so clearly. Too often these are conflated together and it blurs the conversation. Very true. Here it is a success of both, with knowledge setting the lower bound, and money the upper bound. That thin slice in between is "your zone of operational success". It works! Wise words. -

Really difficult for me to tell. 16th century complete Joseon dynasty with Japanese style curved blade for the lettered nobility, you're probably looking at six/seven figures and it will climb fast (e.g., white jade tsuba, tortoise shell koshirae, the hallmarks of royalty). They are almost completely extinct and are considered invaluable cultural artifacts. Late 19th century utilitarian infantry, Chinese-style sword with simple construction, perhaps closer to a high-end Gunto. Here is an interview of one of the whales in the field, he would be the right person to ask: https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2008/12/16/features/Blade-Man-and-the-spirit-of-the-sword/2898663.html The good ones are so rare, when discovered, they make the news (especially if they belonged to a scholar, that is a big deal in Korea): An unlike Japanese swords, there is no NBHTK. Chinese fakes are everywhere, undisclosed repair, etc - if you think Nihonto is filled with peril, beware the waters next to it. Best, Hoshi

-

Hello, They are incredibly rare to begin with and appeal to collectors in Korea and China who operate in a completely different financial league. Finding one is like stumbling on a great treasure. They are rare because the Korean cultural forces that shaped the Chosen dynasty did not value their arms, private ownership was always seen as a problematic matter, and they suffered enormous devastation from wars over the centuries that led to many waves of disarmament. Many of the better Korean swords tend to have Japanese blades, these were a prime export of the time. Here is an example: https://www.mandarinmansion.com/item/joseon-byeolun-geom Compare with the more usual blades found: https://www.mandarinmansion.com/item/korean-ceremonial-saber Best, Hoshi

-

Advice for new collectors from an old dog

Hoshi replied to R_P's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Hi, Priorities changed over the eras. Shortening during the turbulent Muromachi times were motivated by having the best, most functionally advanced sword by your side. It was life and death, no time for nonsense. It wasn’t seen as disrespect for Grandpa’s heirloom - the opposite in fact, it was given a new life to do what it was supposed to do: battlefield duty to protect grandpa’s family lineage. Oda Nobunaga was a serial O-suriage enjoyer and big collector. He wanted the option to use it. Only the curious dreams of the Uesugi Daimyo somehow led to a family-wide proscription on chopping up heirloom nakago. Later you see more refined approaches. Gakumei, Orikashi Mei, Kinzogan Mei, and so on and so forth. They are the fruits of a time where life and death battle royal wasn’t the only grand imperative. And again, it was seen as a sign of respect to the sword to be able to wear it in court. Remember that a Kinzogan Mei by the Ko-Hon’ami was seen as equivalent to a signed sword. You still have this attitude in Japan, where a Kochu Kinzogan or Origami is often said to be equivalent to a signed sword by old collectors. Gakumei were also susceptible to forgeries. You can always transplant a mei from a burned Norishige on your Ko-Uda, and make shenanigans. The alternative is the shenanigan-proof Orikashi mei. But It came later. it was also carried out outside of Hon’ami/Umetada shogunal institutions. And sometimes Mei were messed with for strategic reasons. At some point it became very risky to own a signed blade from a grandmaster for a small, or even large clan. There was always a bigger dog that would gently ask you to part way with the sword in a way you couldn’t refuse. Gakumei swords, swords with defaced mei (filed, chopped midway, half erased by the bohi extension…) - these were protected as they were considered less appropriate for gift giving. The Satake clan is noteworthy for having filed, defaced, extended bohi etc on all their family top swords. They probably got badly burned at some point and took drastic action. There are a lot of social circumstances surrounding nakago condition, and it is quite a fascinating topic. Personally I find Gakumei, Orikashi Mei, ko-Kinzogan, defaced Mei, and partial Mei swords wonderful. They tell the story of their times. Best, Hoshi- 142 replies

-

- 11

-

-

-

-

The hada doesn't quite conform with what one would expect from "The" Shizu. It has a certain Hokkoku-mono flair. The steel is dark, with standing out jinie and chickei. I suggest Sanekage or Tametsugu as more probable than Shizu, after further reflection. What's Mino Shizu? Naoe Shizu? There are wonderful Naoe Shizu, the quality variance is high.

-

No, not Masamune. My best idea is a Juyo-level Shizu Kaneuji. The gunome peaks, the wild hataraki and large nie deposits are textbook. The sugata also matches nicely. The kinsuji may feel borderline Satsuma Shinshinto but the boshi and overall jiba are Koto, early to middle Nambokucho.

-

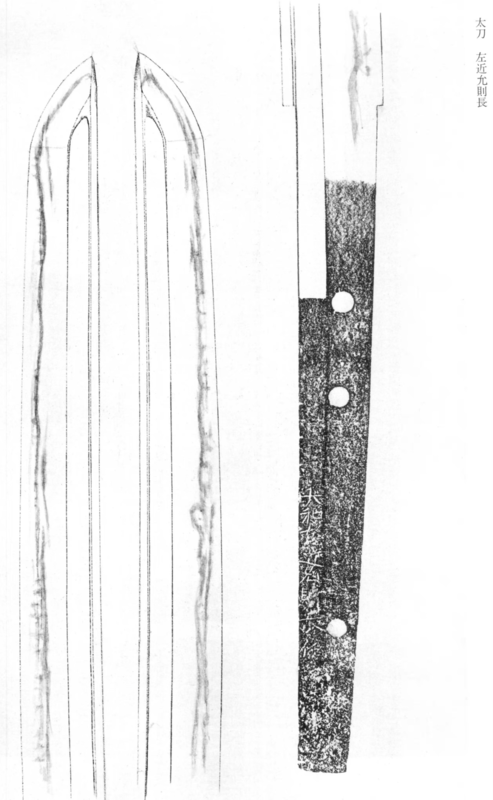

Hello Lewis, Here is what you seek, it is 1310, I believe. However, I do not lend these Oshigata too much credence. They are imprecise, and are not faithful rubbings of the signatures. There is gimei work in there as well, although Kozan is one of the more reliable and famous ones. Here is a Norishige tanto dated 1214 for comparison. I believe you're wondering if your potential Kunimitsu Atelier tanto may have been made by Norishige, and gathering data on signed piece situated within the same time frame to test your hypothesis. This is the right approach! Norishige, out of the Soshu masters with extant zaimei work, has a certain naive calligraphy. As many smiths, he was illiterate and you can see this. Afterall, he hailed from a backwater province considered barely civilized by the military and aristocratic elites of the time. In terms of style, he uses different chisel sizes, and really enjoys accentuating the top and bottom radical of the "shige" character. Dating on the other hand, he doesn't seem to put too much pressure. Thin chisel, very well aligned on the vertical and horizontal direction. Does the date chisel stroke on your Kunihiro indicate that it may have been daimei work by Norishige? I think it's fascinating to see if one can sniff out Norishige, Yukimitsu, or even Masamune's hand out of late Shintogo daimei tanto. I believe we have no established precedent for it as well. It would be of major academic interest for the field. Now for the comparison at hand, the chisel size appear different, broader chisel face. And there is some leftward drift. Norishige on the other hand, seems to quite attached to straight lines. He's very much into his vertical and horizontal strokes. Given that, I would expect his "Kuni" character - if he was ever making Shintogo style tantos - to have a straight and perhaps thick transversal radical. Now, remember that Shintogo had more atelier students than just his son Kunihiro and the three Soshu virtuoso. He had two others sons: - Kunishige (國重)—Son of Kunimitsu, Shintōgo Tarō (太郎), born in the 8th year of Bun’ei (文永, 1271) and died in his 32nd year in the 1st year of Kengen (乾元, 1302) - Kuniyasu (國泰)—Son of Kunimitsu, Shintōgo Saburō (三郎), born in the 1st year of Kenji (建治, 1275) and died in his 64th year in the 4th year of Kenmu (建武, 1338). You can read more about what the old sources say on Dmitry's excellent site. Now this is according to an old primary sources. And if the dates are to be believed, Kunishige is out since he died in 1302. This leaves Kuniyasu as as a possibility beyond Kunihiro! We do not have any extant work by Kuniyasu left, alas. Hope this helps, the quest is noble. Hoshi

-

Why is saving for a sword a taboo ?

Hoshi replied to R_P's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Hello, This is becoming a bit of a murky conversation. This often happens, collectors operate at different segments, value different things, and operate under different constrains, financial or otherwise. Everyone likes a collection that tells a story. It’s a human thing, we are storyteller’s. I think this is the most important, there should be an engaging Gestalt emerging over time. And It’s as much a story about oneself and the story about the object themselves. Back to segments. I don’t think its right to say one should save X before buying etc. I think it’s very reasonable to begin with a humble blade that is at the entry level. Just to feel if you enjoy being a custodian. There is an emotional experience to be had there, and I think ownership is important. Does that mean we should keep doing that? I don’t think so either. There is a much richer personal journey ahead, a kind of quote-unquote Cursus Honorum or honorable passion track where you visit new heights year after year. What matters is the speed at which one learns. And there is an internal component to this, learning what one likes, because preferences change, especially at the beginning where it evolves fast after this first blade. The good news is that it stabilizes also after some time. One day, you find « your thing » and this can be like Jussi’s enamored state with large war swords from turbulent period of history. It can be General Gendaito with special issued blades and family Kamon. Tastes are also shaped by constrains, why would you allow your brain to form attachment to things that are forever out of reach? If you want to collect only Osafune Mitsutada - and there is someone famous who did just that in modern times, emulating Oda Nobunaga - it makes no sense if you can’t reasonably afford it after a few years. It’s not even worth day-dreaming about it. Attachment is the cause of suffering as they say. Our preferences are shaped in part by our economic opportunities, and this is psychologically healthy. But it’s also important not to let your attachment to a particular segment make you lose sight of reality. That’s cognitive dissonance. It’s an illusion, and it’ll harm you on the path of learning, a great deal. « Quality is relative » « Muromachi Sukesada can be just as high quality as top Bizen » « I’ve seen really good Muromachi Mino that are better than top level Soshu » You can be Sukesada collector. There is merit in that. It can tell a great story, but don’t be under any illusion with regards to its standing within the epic historical arc of Nihonto. This is why I like Jussi’s approach. He’s humble, he recognizes that what he’s after is unorthodox and not quality dependent, he’s cognizant of his emotional response, and he longs for the fearsome Odachi and O-Nagamaki clashing during the height of the Sengoku Jidai. The more rustic from overlooked provinces, the better. Back to learning. If you can reasonably do it financially, it’s worth going up the Cursus Honorum. Take progressively bigger risks, see how that works out. Try to identify a good Koto Tokuho sword, and try your luck at passing a blade to Juyo. if you succeed you’ll have absorbed all the losses you might have taken when reselling the the 2-3 smaller pieces that did not make it, and when faced with failure you might learn something important. After that, you should sell some swords, because going through the pain of selling is healthy and important. With that first Juyo firmly in hand, you have contributed to the field is your own small but significantly way, making this sword and its scholarly commentary published for all adepts of the Cursus Honorum who diligently purchase the Zufu volumes and track passes over the years. The mysterious travelers of the Cursus Honorum will notice, and soon you might find yourself part of that community that often visits Japan around the time of the DTI. Provided you're a good human, you’ll be invited to private events that will open your eyes wide in awe, hold onto your hands some of the most significant masterworks ever produced, and find that connection to the sublime. And once you experience it you will remember it forever, and you will be lastingly changed. This was the path Darcy threaded and relentlessly tried to teach to those that would listen. A path traveled by legends such as Paul Davidson, Walter Compton, and many others, still living, whose names are to be discovered along the path. And on that path there are a lot of opportunities for progression. Learn with Tanobe-sensei, discover lost provenance, pass items to Tokuju, and much more. You will learn to navigate another culture and to deeply respect it, and this is perhaps one of most enriching aspects. At the highest levels, the peak of the peak, you will encounter a rarified few that operate at the level of these Ethereal Meito. There, it’s decades of relationship building to create the bonds of trust, deep respect, and commitment required. Even if you have the financial means - which is a rarity in itself - earning the access is an extraordinary feat. At this level, it’s not about “recouping your money” anymore. These blades are priceless treasures and the demand is there no matter what. It will appreciate just as blue chip art. You are safe, there will always be a buyer. The top 10% of Tokuju are such culturally significant masterworks that they hedge themselves from economic downturns. But at this level paradoxically money becomes less important, and choosing who the next custodian will be becomes a primary concern. It’s a responsibility, money comes and go, but such historical treasures call for the most capable and worthy guardians. It is like choosing an heir to the empire. That’s the peak. By the time you reach it, you'll be old. And you might die pretty soon. The Chairman and majority shareholder of Token Corp passed away last month at 77 years old, and he left us a beautiful museum in Nagoya that will educate generations to come. What a legend. RIP, Kouda-sama. Your legacy will endure. To sum up, yes - measure your risk, buy small at first. Play in a field where you can play by virtue of your prospective economic condition. Nothing wrong with that at all, but do not succumb to delusions and cognitive dissonance. You’ll induce yourself and others in error. If you have the financial means, don't get suck accumulating one hundred medium/low grade swords. Seek progression up the ladder of both quality and knowledge, which go hand in hand inevitably. Don’t peddle green papers. Don’t hurt others. Do no harm. Don't be evil. Learn what you like and chart your path. That's the most important. The Cursus Honorum is optional. But it sure is a beautiful journey. best, Hoshi -

Don't pay double with 'Bladetique' and similar.

Hoshi replied to a topic in Auctions and Online Sales or Sellers

Hi, "Based in Japan" - very unlikely. You are probably dealing here with an associate of the infamous '100M $ tachi' swindler which you can look up on this board. No Japanese dealer in his right mind would put such a banner as visual identity for a sword shop. Even if you got it at the auction hammer price, trust me - you dodged a bullet. Avoid Ebay, avoid YJP. You will get burned. Your best bet to find a decent entry level sword is to buy from a reputable dealer on this board. Best, Hoshi -

Hi Carlo, This is confusing I know. Back in the days, when I drew my first Oshigata, I drew the hadori outline of the sword... From this angle, what you see being at the yellow line is the outline of the hadori, the whitening finish that the polisher applies on a traditional kesho polish. What you see in red is the boundary of the true hamon. This is a rather intense hadori job that has been done quickly, and the hadori line doesn't follow the hamon accurately. It is emphasized here to create an undulating impression (the default for hadori, which is created by small circular motions of the thumb following the hamon with a piece of shaped whetstone underneath), whereas the hamon of your sword is composed of angular gunome with deposits of nie. It's a common occurrence to find rather quick and intense hadori works for swords where it is financially irrational to invest thousands of dollars (3K-4K$) and wait for a year to have an appropriate, character elevating hadori finish. This is why western collectors drum sashikomi as the only right finish, with hadori often painted as being untruthful 'make-up' to mask things. Top tier hadori is wonderful however, and appropriate for many types of nie-dominant blades interpreted in a shape that the finger can realistically follow. When looking at the sword under an angle at the light, the hadori will visually vanish (Going from light to dark) and you will see the light reflecting at the nie (Going from dark to light), forming the real border (nioiguchi) of your sword's hamon. Hope this helps, Best, Hoshi

-

This is a truly wonderful sword. Having seen it in hand I can attest to its qualities. Before seeing this sword, I associated Ko-Hoki strongly with the dark, and rather coarse, standing out hada, and while it has its own archaic and wabi beauty, at the top of Ko-Hoki, we find a more refined hada, both finer and richer in dark ji-nie. We can see how these high-quality Hoki blades inspired the much later Soshu revolution, where artists such as Norishige strove to reinterpret these works in his own unique way. Yasutsuna blades are unicorns, with only 22 Juyo designated Yasutsuna, 6 Jubi, and 5 Jubun, and one Kokuho. Seeing one on this board that has been so expertly photographed, filmed, and documented is a great blessing. Thank you Brano. Best, Hoshi

-

Why is saving for a sword a taboo ?

Hoshi replied to R_P's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Hi, Saving thoughtfully for a sword isn't taboo; rather, the true taboo lies in the opposite practice—impulsively accumulating a hoard of stuff because one likes Nihonto. That same collector, ten years down the line, could have been the owner of few but immeasurably valuable masterpiece. I have the firm conviction that collecting skews highly towards rewarding delay of gratification, and I like to think of it as a form of rebellion against the tiktokification of our brains. Our communities shape our identities. In our current timeline, we ought to strongly prefer associating with people who desire and take active steps towards preserving a functional attention span, the capacity to delay gratification, the motivation to carry on diligent study and the savviness to build high-quality social bonds along the way. My desire to help and share knowledge in turn depends whether or not I sense this potential in a curious soul. At the end of the day, we become who we hang around with. So we either police our spaces and create strong cultural norms, abandon the space, or risk becoming something we don't want. Ted Tenold, a wiseman from Montana, once told me that this hobby is like "growing a bonzai garden" - and it stuck with me. Take it slow, prune the leaves carefully, let it grow over decades with intentionality. The meaningful pleasures of life are in the waiting, not in the act of consumption. It is not uncommon for collectors to save for a year, followed by one or two more years between parting with their money and taking delivery. It adds up quickly, six months for a new habaki, one year for a great polish, one year between passing Juyo Shinsa and seeing it for the first time. Three years between the formation of an intention and seeing the results of this intention materialized. These timeframes sound insane to most people, especially when you have Amazon same day delivery and the customer entitlement that comes with it. But I think it carries benefits for character building. There is contentment to be found in doing things slowly, the right way, without cutting corners, as oppose to riding the dopamine-fueled pleasure treadmill to get the next hit. This all sounds good in theory, but this level of patience is hard fought for, especially not nowadays in our neurologically damaging environment, and even then, we all have moments when we're the proverbial five year old in the candy store. It is really hard. It takes a lot of time and intention. Perhaps, we are all bonzai gardens. Best, Hoshi -

Dear Denise, Yes, they are both Kamakura smiths. There is no explicit information on either the Sayagaki or the Setsumei that tilts towards one or the other. Now, let me explain something more important: I would not fret too much over Nidai or Shodai - as in, who made it, in the end. The scientific reason is that we cannot know, we do not have a time machine. We do not even know if NOR238 was really a different person from NOR237. Their period of activity is close, and the old paradigm of attributing stylistic and mei changes to subsequent generation is slowly being replaced a paradigm more consistent with Occam's razor: smith simply changes their styles and mei over time, especially those that have long period of activity and have intermediary pieces in terms of deki that allow for a continuity in interpretation to emerge from their corpus. This could very well be revised in the future. In your specific case, it would make no difference from a market perspective to me, having a blade signed in the NOR237 or NOR238 mei style, given an equally compelling deki. Both smiths are Tokuju capable, both smiths have Juyo Bunkazai blades with similar degrees of preservation in terms of mei. In terms of rarity, blades by NOR238 are even rarer than those by NOR237. And last but not least, to me at least, they are likely to be one and the same smith. I would be 100% focused on the deki when assessing the value of the object. Specifically, where it stands within the corpus of NOR237/NOR238, within the broader Yamato tradition, and in relation to other school founders. Best, Hoshi

-

And here is the key sentence: Notably, there are places where the gunome form continuous groupings, a typical feature of Norinaga’s work within the Shikkake school. The important praise is this: The bright nioiguchi and soft temper line. Bright and soft nioiguchi is rare in Yamato work, and indicative of top tier (i.e Juyo worthy) work for Yamato. As I explained previously, the NBHTK does not make a call on Norinaga I or Norinaga II. It simply states that this is Kamakura period tachi attributed to Norinaga, which can mean either Norinaga I or Norinaga II.

-

Hello Denis, We need the Juyo setsumei of your sword to go further. As a rule: NBHTK only attributes to the second generation (Shikkake Norinaga II, NOR 238) signed works that are identified by the second generation's signature style (which are nijimei and/or contain "Shikkake"). Everything else, all mumei blades, by default will go to Shikkake Norinaga (NOR 237 and NOR 238), without precision on the generation unless made explicitly in the setsumei. That is to say, there is no explicit differentiation between Shodai and Nidai on mumei blades, unless explicitly stated in the setsumei. As for your Oshigata, it fits within one of Shikkake Norinaga's known styles. I can say that it is not his archetypical style, which would features rather tight and conspicuous gunome elements repeating at narrow intervals, which is highly distinctive of Norinaga within the broader Yamato movement. Attached, Juyo Oshigata of a Norinaga I, Denrai to the powerful Matsudaira clan, and zaimei. This blade passed Tokuju on session 9, and is probably the best Tokuju by Norinaga. Notice the tight gunome forming thin ashi all along the surface of the ha. Here is a blade by Norinaga II and bears his distinctive mei. Also a Tokuju, and denrai of the powerful Kaga Maeda clan. Notice the more relaxed notare. While there are still gunome elements and ashi, the structure and repetition is different. I hope this helps. This is not a school attribution. If it was a school attribution, it would simply state "Shikkake" - This is a founder attribution, and it points to Norinaga I and Norinaga II as most probable makers. Both are considered late Kamakura smiths. Best, Hoshi

-

Hello Denis, Lovely sword. Koto period Juyo blades by school founders are highly valuable. We know that with five blades ranked Juyo Bunkazai, Norinaga has a long tail of excellence. My heartfelt congratulations on passing Juyo Shinsa, especially during these hard sessions. And I appreciate seeing good sword being discussed on NMB, thank you for your contribution. As for your blade: Strengths: - Attributed to a school founder, which is rare: we have ~50 blades certified blades by the founder, of which 21 are signed and Juyo+ - Comes with a nice paired Koshirae (This is a big factor in the West, not so much in Japan) - Sizeable motohaba at 3cm, all else being equal, wide blades are much appreciated. - Passed a hard session on the merit of its deki (not a rare inscription type) Unknowns: We cannot judge the deki from the photography provided, so this remains a question mark. We know that its lower-bound is juyo level, but not the upper bound. Compromises: - Mumei (half of them are signed, so they exist, including dated works) - Short: 64.2cm is on the left tail of the Norinaga Daito length distribution Here are some good questions for you to research: - Where is it situated in Shikkake Norinaga's broader certified corpus? Lower Juyo? middle Juyo? Top 10% (Tokuju candidates), amongst the top five in existence (Exceeding Jubi, approaching Jubun)? - Early, Middle, late work? Can we tell at all? Typical, atypical? Where does it fit in the story of Norinaga and Yamato-den scholarship, and do we learn something new about Shikkake Norinaga from this blade? For an example study of a school founder's corpus, see here. The fact that it is a Juyo blade attributed to a school founder is very precious in and of itself. These are amongst the most desirable Yamato blades, Chin-Chin Cho-Cho. You are a lucky custodian. Best, Hoshi

-

The game theory on this is interesting...

-

Hello, This is not a buffet. The Togishi is an artist in his own right. This duality between "hadori bad, sashikomi good" is the wrong way to think about it. Blades are artistically elevated by a sensitive Togishi, who in the process of exercising his craft, decides on the appropriate rendition of the work. Some Togishi are better than others, and in fact this is an understatement. It is not just a matter of being traditionally trained - there are a few Togishi who far exceed all others in the field, and all great blades go to them, which in turns makes it difficult to emerging talent to gain sufficient experience in treating masterpieces appropriately. This is why there is a social component to it, and I think it's appropriate to every once and a while, give an opportunity to a recent winner of the polishing contests held by the NBHTK to work on important swords. This is correct, Ono Kokan, Fujishiro, Hon'ami Nishu, Saito, and other great masters exercise a refined gradient of Hadori appropriate to the blade. Their polishes are precious in their own right. The appropriate amount of hadori on a Masamune blade is not none. The appropriate amount on a run-of-the-mill Kanbun Shinto blade is way, way more hadori. Why? Because the nie is less deep, the nioiguchi is harder, and the hataraki are absent, leaving a 'blank' hamon that is typical of run-of-the-mill Shinto. With a heavier hadori, the otherwise blank Kanbun Shinto will appear with a stronger contrast that is meant to evoke the bright, snowy nie that is typical of Kamakura period masterpieces. The emphasis on "meant to evoke" - because with a trained eye, it of course does not pass. The intention remains. And here I say Shinto - but it's really case-by-case, there are wonderfully active blades with deep nie by smiths such as Hankei, and these should be treated closer to Norishige, which implies a light hadori touch. Another principle: Gentle notare rich in activity is perfect for some tasteful gradient of Hadori applied, the outline of the hamon can be followed by the finger of the polisher and matches the flow. Only on extremely flamboyant hamon and high quality Bizen-den should one truly opt for pure shashikomi in my opinion. When in doubt, better to ask Tanobe sensei. Best, Hoshi