-

Posts

995 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

12

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Ted Tenold

-

Who are currently the best horimono carvers?

Ted Tenold replied to Surfson's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Robert, some of the best horimono I've seen were by Yanagimura Senju who is in the video above. The subject younger fellow in the video is his son Yanagimura Masayuki (art name: Soju). Sadly, I believe Senju san passed away last year, but Soju san has won quite a number of awards for his work. You could try Mishina san as Peter suggested, and also Sasaki Takushi san who between he and his deshi polish many Shinsakuto, or perhaps send an email to Ginza Choshuya as they often have swords with hori by both of them. Edit: Ah, here is a page from Ginza Choshuya with links to swords that both have engraved. http://ginza.choshuya.co.jp/sale/new_generation/new_gene.htm -

I concur with Jacques on the reading of the mei, and based on the history of judgements of signatures for this maker will likely be that it's spurious. There is only one signed Hosho Sadamune tanto, and while it is indeed a Juyo Bijutsuhin, the authenticity of the mei is also regarded as questionable by notable authorities. This sword images posted above show that someone slapped this sword together with a smattering of parts. The habaki is not original to the blade as the size and fit are very wrong and out of synch. The handle is a former shirasaya handle converted. The seppa are mismatched in sizing and base material. None of this is to say the blade itself may not hold some kind of merit, but someone with good eyes and experience will need to see the blade in hand to determine that. Find a show near you if possible and bring it. It'll be best for you and your sword.

-

Recent UK import hassles

Ted Tenold replied to Alex A's topic in Sword Shows, Events, Community News and Legislation Issues

Winner: PaulB, in record time! :D I was wondering who would take a swipe at that after I tee'd it up so well. -

Recent UK import hassles

Ted Tenold replied to Alex A's topic in Sword Shows, Events, Community News and Legislation Issues

I would add that when exporting items to the UK, along with the Harmonic Tarrif Code (HTC) of 9706.00.00.00 and the notation of "Antiques, more than 100 years old", it is also helpful to also write in bold print in the description "RELIEF REQUESTED" which is another key term to alert HMRC that the item is antique and subject to 5% VAT instead of 20%. -

Was hoping to find out more about a blade that was give to me

Ted Tenold replied to Cvzarms's topic in Translation Assistance

Here is another example for comparison from my website; http://legacyswords.com/terukane.html -

Frankly, I would enjoy a lengthy friendly discourse on this, but I'm insanely busy, so I'll have a cuppa and try for a "10,000 words or less" post on the matter. I think the evolution of sword manufacture, the rise and fall of certain schools/traditions, and the success or failure of particular designs, is a matter of greater intracacy than ascribing a hypothesis of superficial aesthetics. However I will offer the following thoughts for contemplation; The Ichimonji schools, through it's origins and development of various branches as accepted by today's scholarship, began in early Kamakura and continued through Nambokucho, a span of nearly 200 years. Are we to believe that the smiths of this school, *and* the various branches, in assorted regions, continued working in a technique that produced inferior weapons, and then passed that technique on to their progeny so that they also could continue to make inferior weapons? Weapons in which the survival of families, soldiers, citys, and political powers depended? Also this methodology was held and or adopted to other subsequent schools that developed their own interpretations on the foundation technique and technology of Ichimonji. Are we also to believe that they were so flawed as weapons that they could not have earned the respect, admiration, and one could argue "obsession" of the major military rulers of Japan for the next several hundred years, *and* survive through the periods of massive and widespread warfare over the subsequent Sengokujidai, all the while being emmulated in design and technique by smiths in the Osafune school during the warring states period? A cursory glance at the numbers shows that 544 Ichimonji Daito are designated as Juyo or better. This is just the Ichimonji school and branches, surviving on their so-called "bling" for 800 years. For the entirety of the Rai school with a strong majority of sugu based hamon (though Kuniyuki and Niji Kunitoshi have some pretty blingy choji examples also) hold 578 daito listed as Juyo or higher, and following Nambokucho, they also faded from existence, with no real smiths to emmulate them until arguably Nosada and then Umetada Myoju and Hizen Tadayoshi (mostly from Nidai on). Speaking of Osafune... Large numbers of flamboyant chojiba in a total number Daitos, of Juyo or higher; 969. Many of them made during the most tumultuous times of warfare, still ubu, or slightly suriage/machiokuri, and still extant, some with big ol' cuts on them testing their inferior design....repeatedly. Moving to Soshu; Hitatsura in it's iconic imagery arrives when Akihiro and Hiromitsu appear on the scene, and in a far lesser emphasized form a little earlier with Hasebe. Saying that hitatsura killed Soshu is folly. First, Akihiro has no daito to reference and shows only wakizashi and tanto, so we don't know if any daito by him were in hitatsura or not, or if he even made any daito at all. Hiromitsu also has mostly wakizashi and tanto, most in varied emphasis of hitatsura, but also has one signed tachi. Now this tachi demonstrates a very important lesson we must all remember; comparing a smiths works in shoto with their works in daito, will most generally show a vast difference in approaches to forging and heat treating. Why? Because they knew what they were making, it's purpose, and what it would be subjected to. Hiromoitsu's singular and signed tachi is not in the flamboyant thick hitatsura, but rather in a calmer more relieved interpretation, with far less muneyaki, tobiyaki, and yubashiri. So the "stiffening" features are far less emphasized, because it's so much longer and subjected to different stresses and application than a wakizashi would be. These second period Nambokucho wakizashi are very thin, made so to enable a thinner cutting edge desired in this particular period of warfare. The aesthetic of hitatsura was incidental to the need of stiffening a blade with a thinner cross-sectional mass. However in the Hiromitsu tachi, flexibility for it's mass and length was required and thus given due consideration with far less hardening in the overall structure. Hitastura's affect on Soshu was not a matter of "video killed the radio star". Soshu fell victim to political, social, and economic changes and simply could not survive the turbulence of the Nambokucho era after the fall of the Kamakura shogunate. Sadamune probably tried to keep the momentum with his move back to Omi (if that alternative holds true) and through his student, Kanro Toshinaga (again, if), but sadly it was not to be. I do agree however, that a daito made in big, ostentatious, radical, hitsatura would garner some suspicion in my own mind for comparitive durability, but if I knew the maker, and he was of a good reputation, and he knew what I wanted and needed, I would then have to trust that he would know how to make it. After all, the first smith to hand a single edged curved blade to his customer that was tired of breaking Chokutos probably received a very strange and skeptical reaction.

- 59 replies

-

- 11

-

-

Lost sword * Edit * Found

Ted Tenold replied to Surfson's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

So sorry to hear this happened to you Bob. I'll keep an eye out also. Any chance it may have been lifted out of your luggage or packing while in transit on the way home? I hate to think of this kind of thing happening at any show, though it wouldn't be the first time. -

Bear in mind that the blade has undergone a number of polishings, during which material is removed and the effects of heat treating are stronger and more defined at the surface than toward the heart of the sword where it becomes diminished and thus changes from its original shape and character. Features such as utsuri are also not always symmetrical from omote to ura, and will often vary in form, consistency, and intensity. If the oshigata is drawn faithful to the blade, I would disagree in calling this "mizukage" which is more or less a perjorative term associated with saiba (saiha), "re-tempering". Origin of utsuri is very commonly seen in ubu blades to arise in advance of or at origin of the yakiba, up into the ji of the sword and then curve to advance along the lenght. Mizukage is a hard 45 degree-ish line that directs from the has side of the sword and up and off the mune. Two distinctly different visual elements. This sword has been ranked Juyo. If it hasn't been remarked as Yakinaoshi (which is somewhat forgivable for Juyo in Nambokucho and earlier), then it's not mizukage. It's utsuri.

-

While I understand and agree with your fundamental view, the variables demand some consideration. I don't think Darcy is establishing a premise that studying swords in images is nearly as good as in hand. He offers a casual estimate of 70% as about as good as one can expect to garner from a two dimensional image of a three dimensional art form. Considering that 70% is a C- in academic grading and just barely passing for credit in some subjects, it's a testimony that viewing in hand is what makes the difference . The best images possible of a Tokubetsu Juyo can't capture the full dimension of what it has to offer visually in person, so I think that 70% is fair to call a ceiling until some new visual technology can get us to 80%. I feel reaching even that by viewing photos on line rely on some pretty important metrics, and the variety of viewers' experiences have to be groomed with a stroke of Occam's razor; 1) Quality and or importance of the item shown in images. A sword which is the one and only Tokubetsu Juyo of it's kind, is truely one of a kind. A turd is a turd. 2) Quality of the images. Professional images of a turd, will likely get you closer to 100% of the viewing experience as in hand, with an extra 10% on top for the time you'll never get back and the image you'll never be able to un-see. Bad images of great swords will fail to even get one to a D+ and 69%. Enter the need for exceptional images on the first level, and a venue to hold a sword in hand to see what the other 30% contributes to acheiving Nihonto bliss. 3) Authentic condition of the item being viewed. By "authentic" I mean the true-to-life, as seen in hand, state of condition of the item itself, in images having not been altered, retouched, or just ommited from view. If the images were a Hershey bar, and you received a turd in the mail, well.... you get the drift. 4) Quality of the viewing platform. High resolution screen, or something else? On a bad screen, the best images of great stuff can't acheive full impression, while turds may get the benefit of the doubt. I concur with Darcy's views on shows, the reasons for their demise, and the course they should be steered toward these days.

-

Orin, Since your location is shown as Florida, take it to the sword show in Tampa the end of this month. https://www.southeastshowsauctions.com You'll be able to meet a number of the members here on this forum who attend the show as well as others with a great deal of knowledge and experience in greater Asia antiques and artifacts. Hope this helps! Ted

-

Steve, To me it looks like a mei that was previously closed up, and filed over. The evidence of such a procedure is certainly easier to see on a new sword since there's no patina cover over the "bruising" or artifacts of a previous mei. Perhaps, (and this is just a speculative guess) the smith made a couple blades for a client and the order or circumstances changed so it was altered to accomodate selling it. All newly made swords in Japan must be signed, so it could not be made or turned into a mumei sword (aka: Kagemono) like in the old days. Just my thoughts.

-

Chris, Yes, I guess I missed the tone on that one. Entschuldigung

-

Inspections and the criteria for acceptance clearly became more relaxed as the war went on. I have seen many Gendaito that were flawed in ways that make them undesirable for collectors today, yet they passed the "inspection" and received a stamp. Perhaps the state of polish was the reason they passed as the flaw may not have been visible yet, but also these were to my memory, all in the years of 1944 and 1945. Raw materials, time, resources, and moral were all diminishing at an exponential rate by that time. Also, the Yasukuni records show a tiered price for their blades indicating that quality was judged and prices charged based on several levels. Better quality = more ¥.

-

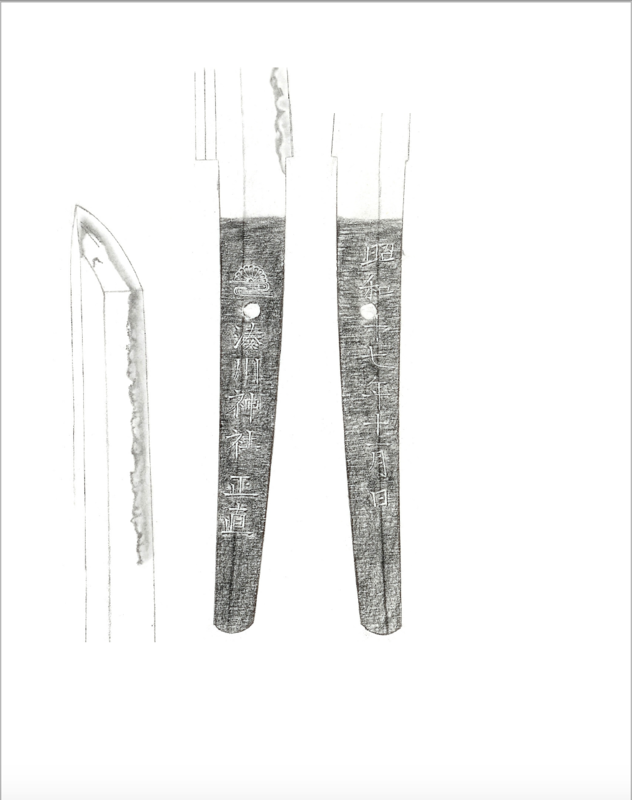

Ed, et al., The reasons for the price dispairity between Minatogawa and Yasukuni is mult-faceted. First and foremost, there are far more Yasukuni still extant because the vast majority of Minatogawa swords are at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. Second, the production numbers are much higher with Yasukuni swords which had not only more smiths working, but a 7 year head start over Minatogawa productions. Third, Yasukuni blades were typically made available for purchase by officers while (it is thought) Minatogawa blades were directed to and issued by the Naval Academey, and Naval War Staff College to graduates. While there are records of production and acquisitions for Yasukunito, there are scant records for Minatogawa as theirs were either destroyed in air raids or by Navy Command perhaps. Fourth, on a wholesale level, the workmanship is generally quite different. It is my opinion that Minatogawato nose ahead above Yasukunito in quality on the whole. Minatogawa swords were made in the spirit of Ko-Bizen and can exhibit some utsuri, nie, deep ashi, and other fine elements. I have seen one Minatogawa blade with a serious fukure, as well as one complete fake. I have also seen a couple of the smiths work which was done outside the shrine and their work was consistent in quality, style, and appearance. Fifth, simply stated; romance. Navy items just have more appeal to some collectors. So at the end of the day, Occum's razor applies in that Minatogawa swords are rarer both at a matter of origins and results of attrition, with a different workmanship, (perhaps) a qualitative edge, and different appeal. If a Yasukuni sword will command lets' say a range of $4500-$6000, then it's natural that the factors associated with Minatogawa will command an accordingly higher price. Of course the standard caveat in this is that each swords value is beholden to state of preservation, condition, provinance, accompanying mountings, etc.. Here is an oshigata of a Minatogawa sword by Masanao that I polished in 2010. It indeed had visible bo utsuri in it.

-

Honjo Masamune found!! (well almost... maybe)

Ted Tenold replied to Adrian S's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

If one looks long enough, one sees what one really wants to see.... -

Piggy banks all over the world should be shaking in their little porcine porcelain hooves....

-

Generally the habaki is made after the blade is polished through around kaisei or chu-nagura, then goes to the sayashi. However there is the rare exception that a habaki is made for a polished sword (hopefully by a skilled and careful shiroganeshi), and I have, in the past had them made for a sword and to fit an existing shirasaya or koshirae when either of those are particularly special and/or important, but it's not cheap, nor is it optimal. A used or reproduction habaki will invariably have some kind of deficiency in proper fit and/or dimension that will make it look awkward, prevent proper fit and alignment of the nakago ana in the tsuka, and can even damage the sword. One can expect to pay about $500-$600 dollars for a well made, properly fitted, and nicely finished copper habaki. Between the cost of buying a used one, the time to find one that fits, and the risk of the damage, it's prudent to consider the costs the risk of damage bring for a cheaper habaki.

-

Dti Dates For 2019

Ted Tenold replied to Keichodo's topic in Sword Shows, Events, Community News and Legislation Issues

Thank goodness it's back to what I consider normal. -

Also, I believe there are some significant and appropriately stringent mandates on how Kokuho works of any kind are transported, displayed, and handled. So it would be naive to expect that the original Sanchomo could be casually displayed open-air for a promo such as this.

-

I was wondering when someone would notice it was not *the* actual Sanchomo. It is a Sanchomo utsushimono by Ono Yoshimitsu, who is widely known for his superb re-creations of it. Getting the real Sanchomo for such a promotion would be nigh on impossible, so this is the best stand in one could reasonably expect to obtain to fortify the fund-raising effort.