-

Posts

1,105 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

5

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by DirkO

-

I think your choices are limited - Massimo Rossi would be my bet: https://www.facebook.com/100063626135305/photos/

-

Textbook no, but looking at the design, it's close to Yagyu, albeit less subdued. So late Yagyu?

-

The only reason I have one up for sale is because I know some people don't like to order from Japan. Obviously this is my spare copy

-

Not buying at the moment, but I think especially the Kanekuni is a really nice package!

-

For sale is 1 copy + English translation. Advantage is it's already in the EU, so no additional customs. Limited Ed to 500 + signed by author. The book features high-resolution photographs of Nobuie tsuba, enabling readers to observe appraisal points, stylistic changes, and variations in signature across different periods.The quality is sufficient to examine iron textures, chisel marks, and forms from the mimi to the seppadai. This makes the volume not only a treasure for enthusiasts, but also an invaluable academic resource for researchers. Building upon Ito Mitsuru’s decades of scholarship, the book presents both well-known and newly identified Nobuie works in a clear, structured way. Set against the dynamic cultural background of the late Momoyama and early Edo periods, it explains the characteristics of the hanare-mei and futoji-mei works, traces how these signatures evolved, and explores the aesthetics behind them—offering a fresh perspective on Nobuie studies. A complete English translation and commentary on Nobuie — in softcover. This comprehensive edition includes every hanare-mei and futoji-mei Nobuie description, along with a substantially expanded commentary and glossary. Price 330€ + shipping

-

Sent test email

-

Maybe an interesting point of view by Mitsuru Ito (rougly translated, probably some small faults in there) February 9, 2025 Nittoho Yamanashi Branch Regular Meeting About the Hitsu-ana Holes on Tsuba 1. No Hitsu Late Heian to Late Edo Period These are the originals, and old tsuba no hitsu are highly valued. 2. Square and Yamagata These are old, elegant shapes with a taste that are suited to thin kozuka and kogai, and originals are rare. Kamakura (?) to Early Muromachi Period Square and Low Suhama Shape 3. Square and low Suhama shape Kamakura?~Early Muromachi period This is also an old and elegant shape suited to thin Kozuka and Kogai, and there are few originals remaining. It is thought to have originated from the same period as 2. 4. Thin half-moon shape and low Suhama shape Kamakura? ~ mid-Muromachi period This is also an old, elegant shape with a taste that is suited to thin kozuka and kogai, and there are few originals remaining. It is thought to have originated from the same period as 2 and 3. During the time of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu. 5. Both hitsuana are thin and crescent-shaped. This shape is seen in Kyoto porcelain from the Northern and Southern Courts (Nambokucho) to the mid-early Muromachi period. It is also seen in older armor makers. It is also found in Kamakura, Owari, and Koshoami. 6. Both hitsuana are Suhama-gata. This style is seen in many tsuba from the Momoyama period. This style was seen in Hirata Hikozo, and continued to be made in Higo afterwards. 7. Thick crescent shape and high Suhama shape are the most common shapes from the late Muromachi period to the late Edo period. Slightly slender ones are from the Muromachi period. In the time of Goto Norimasa, there were also ones with large cabinets to accommodate larger poles.

-

Looks like the cert of the website expired, causing issues for most browsers seeing they enforce HTTPS. Common Name (CN) militaria.co.za Organization (O) <Not Part Of Certificate> Organizational Unit (OU) <Not Part Of Certificate> Common Name (CN) R11 Organization (O) Let's Encrypt Organizational Unit (OU) <Not Part Of Certificate> Issued On Tuesday, July 8, 2025 at 12:34:23 PM Expires On Monday, October 6, 2025 at 12:34:22 PM

-

Hi Jean, took me a while to track down the original Japanese text, seeing I had this on file and I probably used Google Translate or something. Here's a new translation using AI, which I think make more sense: Japanese: 1975年(昭和50年)頃 砂鉄を吹いて鐔の地鉄を作ろうと考え始める。それ以前は洋鉄使ってみたり、江戸時代の古鉄を集め刀匠に依頼して板状に伸ばした鉄を使用し鐔製作を行っていた。 Romaji: 1975-nen (Shōwa gojū-nen) goro, satetsu o fuite tsuba no jitetsu o tsukurou to kangae hajimeru. Sore izen wa yōtetsu tsukatte mitari, Edo jidai no kokutetsu o atsumete tōshō ni irai shite itajō ni nobashita tetsu o shiyō shi, tsuba seisaku o okonatte ita. English translation: Around 1975 (Shōwa 50), he began thinking about smelting iron sand to produce the base iron for tsuba (sword guards). Before that, he had experimented with using Western iron, or gathered old iron from the Edo period and asked swordsmiths to forge it into plates for use in making tsuba.

-

made by Naruki Issei (成木一成 ) - mukansa 2009 - he was a very prolific tsuba maker and especially his Owari tsuba were very nice Born on September 10, 1931 (Showa 6) in Nakatsugawa, Gifu Prefecture, as the eldest son of Seiichi Naruki. 1945-1950 (Showa 20-25) He studied ancient ceramics under Fujio Koyama and Toyozo Arakawa. In 1960 (Showa 35), he was unable to move his lower body due to illness and had to abandon his research into ancient ceramics. He was deeply impressed by an iron tsuba his father showed him, and began researching and prototyping. 1963 (Showa 38) He began full-scale production of iron tsuba in Saneto, Nakatsugawa City. 1966-1969 (Showa 41-44) He learned the Kaga inlay technique from Isamu Takahashi. Around 1975 (Showa 50), he began considering creating the base metal for tsuba by blowing iron sand. Prior to that, he experimented with Western iron and collected reclaimed iron from the Edo period, which he then commissioned a swordsmith to roll into sheet form for his tsuba crafts. In 1977 (Showa 52), he held his first solo exhibition, "Tracing the Four Seasons of Mino," at Ginza Matsuya. He expressed the simple yet powerful painting of ancient Mino ceramics on his tsuba. He was awarded the Gifu Prefectural Governor's Award for Outstanding Craftsmanship. In 1978 (Showa 53), he began making tsuba from his own steel. He was awarded the Medal with Dark Blue Ribbon. He held his second collaborative exhibition, "Reproduction of the Tetsuhirumaki Tachi Koshirae," at Ginza Matsuya. In 1981 (Showa 56), he was designated a holder of an intangible cultural property by Nakatsugawa City for his iron tsuba-making techniques. In 1982 (Showa 57), he began performing the entire process, from charcoal making to tatara (smelting) work. From November 1982 to January 1983, he worked daily on the kettle pressing and kept records. He collected iron sand and iron ore from over 50 locations across Japan. In 1983, he held his second solo exhibition, "Making Tsuba with Homemade Steel," featuring homemade steel made from iron sand from various regions. He compared iron made from iron sand and iron ore from various regions across Japan. He also published "Making Tsuba with Homemade Steel." In 1986, he received the Medal with Yellow Ribbon. In 1987, he held his third solo exhibition, "Yagyu Thirty-Six Immortal Poets Tsuba," at the Kuwana City Museum. Yagyu Ren'ya passed away just as 31 original Yagyu tsuba had been produced. The drawings, drawn 20 years later, reveal that the illustrations for the remaining five tsuba are unknown. Naruki, based on the secrets of their names, also produced those five, resulting in a total of 36 pieces on display. In 1998, the "Tsuba: The Keystone of Japanese Swords: Naruki Kazunari and Ishida Tetsuo Exhibition" was held at the Hoshi to Mori no Uta Museum. In 1999, he received his first Grand Prize (Chairman's Award) at the Nittoho New Masterpiece Swords Exhibition. Since then, he has received the award 11 times in a row, and his award has been included in the "Special Exhibition: The Beauty of Tsuba: The Challenge of Tsuba Craftsman Naruki Kazunari." In 2000, he received the Grand Prize (Chairman's Award) at the New Masterpiece Swords Exhibition. In 2001, he received the Grand Prize (Chairman's Award) at the New Masterpiece Swords Exhibition. The "In Pursuit of the Purple Rust-Colored Steel Bark: The World of Naruki Kazunari" exhibition was held at the Hoshi to Mori no Uta Museum. In 2002 (Heisei 14), he received the Grand Prize (Chairman's Award) at the New Masterpiece Sword Exhibition. Held the exhibition "Pursuing the Beauty of Naruki Kazunari's Worldwide Iron Tsuba" at the Gifu Prefectural Museum. In 2003 (Heisei 15), he received the Grand Prize (Chairman's Award) at the New Masterpiece Sword Exhibition. In 2004 (Heisei 16), he received the Grand Prize (Chairman's Award) at the New Masterpiece Sword Exhibition. In 2005 (Heisei 17), he received the Grand Prize (Chairman's Award) at the New Masterpiece Sword Exhibition. In 2006 (Heisei 18), he received the Grand Prize (Chairman's Award) at the New Masterpiece Sword Exhibition. In 2007 (Heisei 19), he received the Grand Prize (Chairman's Award) at the New Masterpiece Sword Exhibition. In 2008 (Heisei 20), he received the Grand Prize (Chairman's Award) at the New Masterpiece Sword Exhibition. In 2009 (Heisei 21), he received the Grand Prize (Chairman's Award) at the New Masterpiece Sword Exhibition. Certified as a non-judgmentalist Since 2010 (Heisei 22), he has entered competitions every year. Since he was non-judgmental, he did not receive any awards. In 2011 (Heisei 23), he was awarded the Gifu Prefecture Traditional Culture Inheritance Award. In 2013 (Heisei 25), he held the exhibition "The Beauty of Tsuba: The Challenge of Tsuba Craftsman Kazunari Naruki" at the Gifu Prefectural Museum. He passed away at the facility in 2022.

-

Already reserved a couple of copies with the softcover English translation (due end of October). Indeed, don't want to miss out.

-

For those of you who haven't noticed - Ito Mitsuru (well-known Japanese collector which you know for writing the 3 Higo books, Nobuie articles, book on Katanakake,...) has started a blog. This looks like it will be well worth the read. Blog

-

Yes, they're usually available locally before they're put online. Some shops also work with magazines and they refuse to sell anything online for a certain grace period, making sure all subscriptions get a fair chance first. However, online doesn't mean that non-Japanese can buy it. In 2 cases when I inquired about a piece I was told it was for Japanese market only and they don't sell to foreigners. So I had to involve someone locally as an in-between to buy those pieces on my behalf.

-

For me it's a Kunitsugu unokubi zukuri naginata of 53 cm, where the first 40 cm is double edged, which is quite rare. A very elegant piece, wonder where it ended up.

-

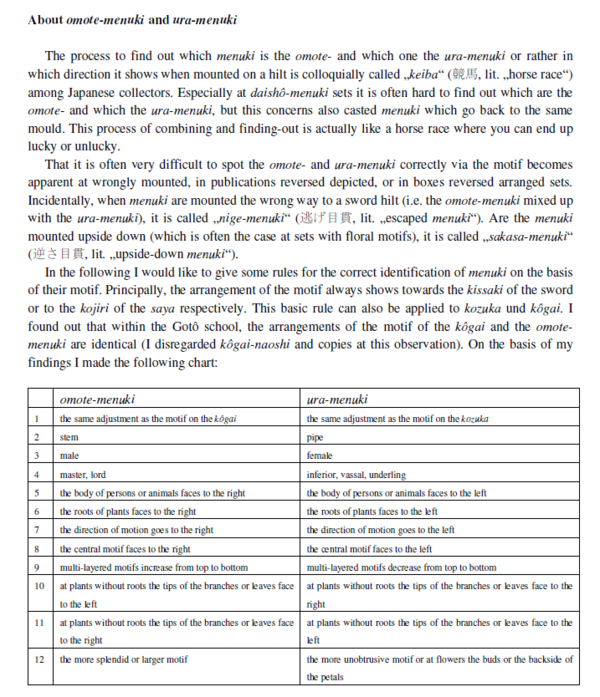

Great reference Brian! Allow me to add this as well (Menuki – Sono rekishi to igi ni tsuite - Iiyama Yoshimasa - extract from Token Bijutsu 09/2011 - translated by Markus Sesko)

-

Also if you have an idea about what you're looking to buy - you can always post in the 'wanted to buy' section. It's often easier doing deals 1 on 1 with people. Obviously you need to validate if the price is acceptable, but you need to do that with shops just the same. And shops usually have a high markup. In any case you've come to the right place. This is the biggest online nihonto forum and a lot of people here are very helpful. You'll get the odd remark every now and then, but please try to see past that, at heart we're a friendly bunch. If you don't know that much about nihonto and you are a bit concerned about resell value, I would opt for NBTHK papers. That will give you some reassurance about authenticity. The bigger the nametag without papers, the larger the chance it's not what it's portraying to be.

-

Although the tsuba has a lot of nunome zogan, I wouldn't call it good nunome zogan. Good nunome zogan actually means that you barely see the cross-hatching, seeing that part was reworked/cleaned up after the inlay. Here the zogan was prepared without knowing how large and where the inlay would come. Then afterwards no care was taken to clean up the prepared surface. See how in the above picture the prepared crosshatching was cleaned up and only the bare minimum outside the inlay is left.

-

Also letting either side have the last word as if it were a definitive conclusion might be a bad idea - ideally one of the admins would do a post summarizing the different views and then lock it.

-

Again, I've never had issues importing tsuba. 2 purchases in December arrived without any problem. I stated harmonized tariff 9706 as usual and also paid the reduced import fee (6% or 9%, I always forget which one it is). Currently have another one in transit, should arrive in a week or so after the usual delay.

-

About collecting in this field I think this is a must read (by Guido Schiller): Collecting.pdf

-

Tetsugendo Naomichi used different kanji (尚道)

-

According to the signature 政長 , several options: - Kikuchi school - Tsuji school - Yasuda school Yasuda (安田) school seems improbable - they usually applied nanako and almost never signed their work, also working for the bakufu their designs tend to be more formal. Kikuchi (菊池) school or Tsuji (辻) school - could be any of these looking at the style and design.

-

on the other hand - you need to reply - otherwise these statements go unchecked! Context needs to be provided.

-

Wouldn't the people be shown on the roads then and not beside them? I like the idea though.