Keith Larman

Members-

Posts

50 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Keith Larman

-

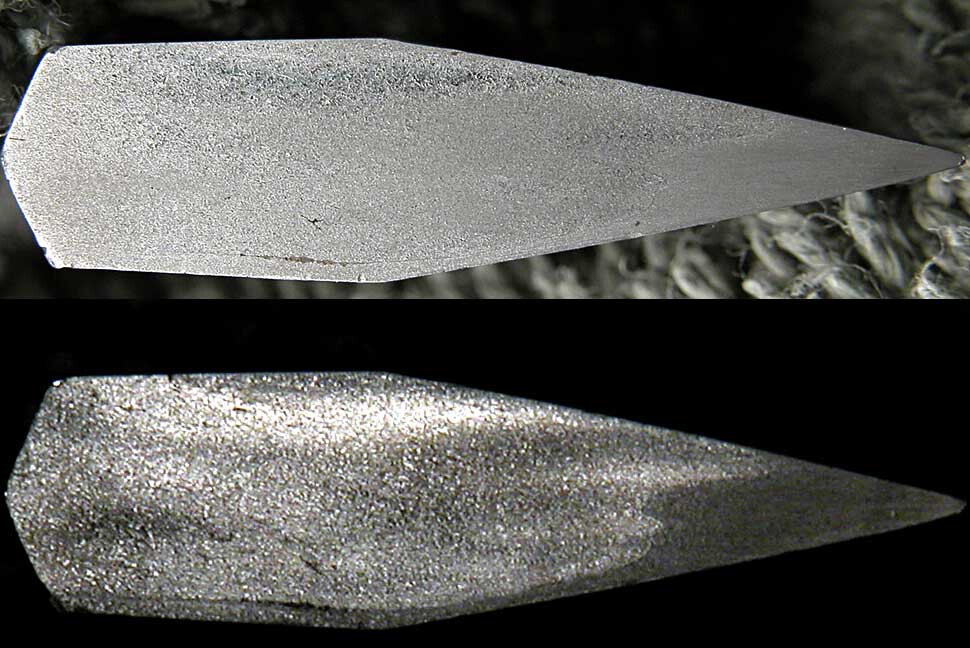

Just to add an observation -- I posted the particular cross sectional picture because it illustrates something you also see in the other images done from cross sections including articles already referenced. More often than not the skin steel is rather thin and when you cross section you'll see that the subsequent forging distorts things quite a bit. Sometimes the core steel is dead center. But usually the core steel seems to wander closer to one side more than another in points of the blade. Remember that after that critical welding to create the laminated blank the entire thing is drawn out. That forging and then subsequent filing by the original smith sometimes seems to leave you with areas where the skin steel is a lot thinner than you might have thought. In the photo I posted notice that one side has virtually no skin steel left. I'm pretty sure the blade was sectioned because core was showing elsewhere on the blade. It has been polished a few times obviously. And the hamon is a bit low. But there is still a fairly decent hamachi and munemachi. So it hasn't been polished way too much (by most standards). But clearly the blade is already tired. If you were looking at a shinto piece with the same hamachi and mune machi and when you look down at the nakago you'll see there isn't much change from the nakago yasurimei "height" and the "height" of the polished steel... You'd probably guess it had a lot more polishes in it. Or at least one more. But this one was already showing core... And short of somehow sectioning a blade to see the relative locations of core and skin any significant polish can potentially expose an unwelcome surprise.

-

Ah, heck, can't make it add the attachment. Let me toss it on my site and do it from there...

-

Well, since I happen to have that very nakago on my desk... here's a quickie scan from my inexpensive all-in-one scanner/printer/etc.

-

Here's another cross-sectional photo from the same set. I repolished the face and shot it under different lighting and also edited it in Photoshop in different ways to make different things visible in the image. One of these days I need to resection them all and shoot them. Just fwiw.

-

I'll be there with some stuff from our (me and Ted Tenold) website Moderntosho. A few gendaito, kogatana, that kind of stuff. I'm also bringing along a repolished/remounted Ichiryushi Nagamitsu with Hozon papers from the NBTHK. Kinda interesting to see that on a Showa smith like Nagamitsu. I know Ted has a lot of stuff from his http://legacyswords.com/. And he has other things not on the site that are really nice. We'll be sharing a couple tables. And I'm bringing my family along too this time for a sort of long weekend deal. Should be interesting. I'm really looking forward to the NBTHK American Branch display. I always tank at the kantei, but the education is always invaluable.

-

From what I can tell many of those who have seen his work in person and really know their stuff are willing to pay top dollar for those pieces. I think there are two themes in this thread. One is valuation of art and that is always a complex issue. The second is the quality of the work of Kiyomaro. The first issue we can all talk about because it is a general thing. The second is something that unless we've had personal experience with good examples of his work ultimately it becomes little more than idle chatter. To use myself as an example, I really can't comment all that much on Kiyomaro's work because I don't have personal experience with it. I've seen lots of photos. And from what I've seen I'm seriously impressed. But beyond that all I'm really left with repeating what others say. And while an argument from authority doesn't give an absolutely correct deductive answer to a question, authorities with access, knowledge and experience with the object of discussion are certainly better situated to have a more useful opinion... No, I'm not going to say that *I* feel that Kiyomaro's work was in the top 10 historically. That is patently silly because I've not sat at a table and handled all that work. I've seen some *really* nice stuff in person. I've been able to handle many nice swords. But nothing like what some have been able to see sitting the NBTHK in Japan with Tanobe sensei. Or at some of the top level shops in Japan. I think Guido's original point about having all those who have actually handled Kiyomaro's work raise their hand is a very important point here. Many who have had extensive experience with his work and the other masters have little problem putting him in the top levels. So that combined with the very colorful history make for a potent combination. Would Muramasa stand on his own merits if it weren't for the entire Tokugawa thing? Kiyomaro seems to generate admiration that goes well beyond the "story". Sigh. I need to get to Japan this fall for the Dai Token Ichi. Now Kiyomaro has jumped to the top 5 of my "must see in person" list.

-

That listing also says it was a katana... Unless I'm misreading the section.

-

Yeah, I was talking with a friend yesterday about this thread and the name Van Gogh came up in our conversation as well. Lots of parallels. Died very young (Kiyomaro was 41 or 42?, Van Gogh under 40), brilliant, tremendously productive in those years, and seeming came out of no where doing stuff so far beyond everyone else that it was almost scary. Genius like that doesn't come around every day. Nor every decade. Nor even every century. I have the book from the Kotetsu/Kiyomaro exhibition Guido talked about. Amazing book and I'm so glad I got a copy. Kiyomaro's work seems to bloody near electrified in comparison. And I can only imagine (or maybe I can't) how much more amazing they must be in person. I frequently go to a local museum when I need a break -- the Norton Simon fwiw -- and the first place I go is to look at Van Gogh's "Portrait of a Peasant". Photos of the painting do not do it justice. I could stare at that painting for hours. And have. It is alive. Anyway, my point being that Kiyomaro wasn't just "any" smith. He wasn't just a "hot" smith. He wasn't just a "popular" smith. He was a great smith, he was an unusual smith, he was someone who appeared apparently out of nowhere doing just incredible things. So yeah, there's a lot of "sizzle" that goes along with him, but that sizzle has substance underlying it. He is a profoundly important smith and an amazing piece of history. So his work is going to command a tremendous premium. We often talk about "art" here on these boards. With Kiyomaro there is no doubt we're talking about a true artist (whether the work appeals to you or not). And so I think all the comparisons to Picasso, Renoir, Van Gogh, etc. are all dead on. And Van Gogh in particular. It isn't just he work anymore. It is everything. The work, the place in history, etc. And from what I understand that isn't exactly a huge price for Kiyomaro's work... So someone could say "How come it is so cheap?" For many owning a single Kiyomaro could be an entire collection. Lord knows I will never own one unless I happen to find it at a garage sale in gunto mounts...

-

Hey, Brian, thanks... FWIW there are multiple things at play most likely. How many of you guys in drier climates get swords from Japan in Shirasaya only to find the fit too tight a month or two later? To the point of even splitting the saya sometimes? Welcome to the world of climate differences. Wood likes to expand and contract (swell/shrink) depending on heat and humidity. Next add to the equation a quality tsukamaki job. As already mentnioned that can compress things further and make them even tighter. FWIW when I'm making a new tsuka (especially for a practitioner) I start off with a snug shitaji. Not super tight, but consistenly snug. No rattle but not "use a hammer" to get it off tight. By the time a full wrap samekawa has been tightly bound and dried, well it gets tighter. When I'm waiting for the glue to dry on the same on the core I'll often gently tape the tsuka core onto the nakago to help keep the interior shape intact just in case. Next once the tsukamaki is done it often won't seat anywhere nearly as easily as when it was just the core. I get it on the nakago asap to make sure it settles into its new, compressed, tight state. And this can be a problem, especially if you have a soft metal/nice/fragile kashira. It isn't just that whacking it with a soft mallet might damage the detail of the surface, you can often fairly easily "taco" the kashira. Sometimes when you see a kashira where the ha and mune sides seem "flared up" a bit and the center of the face of the kashira looks "funny" for lack of a better term, that usually means the sword was either dropped directly on the kashira *or* someone whacked it and deformed the kashira on the core itself. This is a real possibility with shallow kashira as the ana for the ito is close to the face. That means you "slot" the end of the tsuka shitaji rather than drilling through. This means there is no wood core inside supporting the face but wood on the ha and mune. So you whack with the mallet, even gently, and voila, you've just reshaped your kashira... Assuming this is a new core that you had rewrapped: My advice is to slide up as far as possible on the nakago. Gently whack it with your palm a few times at the kashira to move it as much as you can without causing massive bruising. Then let it rest a day or so. You're letting the wood fibers in that section compress a bit and "set" into place. The best time to do this is on a warmer, wet day if possible. that causes the wood to swell and expand making it easier to get it together. Regardless, wait a day or two, remove the tsuka gently and carefully then immediatley try to put it back on again. Whack it some more with your palm since you're not likely to damage the kashira with that. Refresh that bruise on your palm. Hopefully the tsuka will push up a bit further. Be patient, it may take weeks but you can possibly get it back onto the nakago. If this is an antique core or if the above doesn't work... You need to have someone who knows what they're doing rasp out the interior with a tsuka file and get it fit. That takes some experience and sensitivity to where things tend to bind. They will need the entire sword, obviously. Finally... As an observation... I rarely take on rewrap jobs unless the customer will leave the entire sword. And I often refuse to do rewraps on other people's craftwork unless I know their work. Too many variables. A good wrap should be tight. Tight can adjust the fit. And getting it back on the nakago *right away* is the best time to do it. And if it is too tight then they have everything they need to adjust the fit and get it right. So it is always best to have everything together when doing that kind of work. If you're talking about an ancient tsuka it usually doesn't really matter. Most of the times you may tension the ito quite so much if you're concerned about cracking old wood. And they're usually pretty loose at that point to begin with. Just my experiences doing both new and rewrapped old tsuka for both old blades and new. FWIW.

-

The only problem with doing them with a drill press is that you need to put a bit of pressure on the stuff to cut into it. And since it is relatively flexible in longer pieces it isn't always easy. Like I said, the reason I use the precision lathed delrin mekugi on new mounts is that I can get them with a precise machinist's taper to match my tapered reamers. So the mekugi is absolutely flush throughout the entire mekugi-ana. Just keeps things more stable, tight, and solid. Otherwise I generally just use a big chunk of susudake I have, cut out a piece, and file it to shape by hand. If it is for an existing antique you'd probably be better off doing it that way anyway. You need to match the dimensions of what you have and you probably don't want to ream out the mekugi-ana especially if there is tsukaito already wrapped around and in the way. But yeah, Ted is settled in at his new place in Montana. Been settled for a few months now. We've all been away at Tampa, however, for the Token Kai. I don't think he's going home until tomorrow.

-

What Ted uses is Delrin. I use it as well. Basically get a friend to lathe them to a consistent taper. Then we use a machinist's tapered reamer to ensure the mekugi-ana of the tsuka is identical in rate of taper. That ensures a really nice fit. Well done they'll last a very long time and stay very snug and tight. You might just contact Ted directly and see if he has any spare long pins. And fwiw black horn mekugi are beautiful, but aren't all that helpful for a sword seeing use. They're relatively fragile and tend to break fairly easily. But if they aren't being used horn would be fine too. Just don't swing it... And Guido has a really good point. At the last Tai Kai I was at I helped a few of the Japanese sensei doing the sword inspections prior. I was shocked at what people were using as mekugi. Lots of mekugi made of chopsticks, deformed ancient mekugi, pieces of wood, etc. ended up in the trash. We made a ton of new mekugi that day out of susudake and since I was away from my workshop I was away from my tools. Susudake is *very* tough, holds shape quite well, and is a wonderful material. Next time I'm bringing more tools and I"m premaking a bunch of mekugi. Another source of very good bamboo for mekugi is at some craft stores. Here in the US some of the craft shops carry Japanese bamboo knitting needles. They come in all sorts of sizes and it is almost the same as top notch susudake. They cut the bamboo from the same parts of the culm, they season it, etc. Very good stuff.

-

And on Mythbusters. I saw those guys trying to cut one cheapo production sword with another cheapo production sword. I don't think they know enough about the real deal to even begin on something as arcane as this... But I love the show anyway. Some nights its me and the 6-year-old sitting on the couch eating popcorn watching those two loons try things out. Now *thats* my dream job...

-

You should give Patrick Hastings a call about it. We've chatted about that one a lot and I *think* Patrick did some experiments a while back with the effects of work hardening on copper. And keep in mind we're not talking about going fully hard in the work hardening. That will actually make the piece brittle. But some hardening is inevitable in the working of the piece and it takes very little to significantly increase the hardness of copper (and sterling silver for that matter). I'll also point out that I'm not talking about a large, obvious issue here. But it is one reason why some swords develop "slop" in the fit of the tsuka very quickly. I have seen multiple "custom" sword mounts where the habaki had indented just a bit at the mune machi (and I assume ha machi). It wasn't really visible until you looked closely or removed the habaki from the blade and looked at the imprint. But once off it was obvious where the extra movement came from. And if the sword is being used for even just iai "air cutting" that bit of "slop" in the fit translates into vibration and an increased rate of wear and tear to the tsuka shitaji. When everything is tight all parts become a larger "whole". No play, no movement. Hence no vibration to cause problems. Just a small bit of work hardening from dead soft to around half hard will significantly reduce that. Basically the notion is that fully annealed is too soft. But partially hardened is in general hard enough given the forces involved. So if we're talking half hard even rather enthusiastic use will be much less of a problem. And normal use is no problem at all. Fully soft? Well, on a sword being used even just for iai you might start to see a little rattle in a few weeks or months. It's all about keeping the entire rig snug and tight. But drop Patrick a line. I've talked with him about it many times and he's done a lot of fooling around with the effects of work hardening on copper in his shop practices.

-

Oh, and I forgot to add that one of my sensei trained in one of the smaller MJER lineages (the MJER lineage tree is *very* bushy). In general their training a couple decades ago was mostly individual kata cutting nothing harder than air. But once or twice a year they'd gather for a cutting session to validate their form, especially with some of the more difficult draw cut sequences. In their case they used certain plants. Others have used bundles of straw. These guys were not at all influenced by the various "WWII Imperial" training groups. Tameshigiri wasn't a major part of their training, but it was still a part of it. And while I know of major styles that don't do it and even some that expressly forbid it, most have it somewhere in the training. But yes, some styles today have focused heavily on the tameshigiri component when in reality most would use it only as a sort of "check" on form done only occasionally and it existed only in a much larger framework. But it isn't like it wasn't done at all...

-

I'm not sure how examining the photos helps if we don't know if the habaki on those swords were work hardened or not. If they were, well, I'd say there you go, more evidence for work hardening being a positive thing. And I'd also point out that koshirae on swords used in battle were reportedly remounted fairly often. So while a sword may have been used the various parts of the koshirae including habaki may have been replaced, perhaps even multiple times. Especially when blades are repolished due to damage in battle and remounted to be used again. You can be sure that much of the time the habaki was replaced at that time as well. And I've seen poorly made habaki get ripped apart in "conservative" usage. One was a silver habaki that was pretty darned soft and it started "bulging" at the mune machi after a month or two of solo iai practice (no cutting involved -- well, nothing but air). I ended up making him a new habaki out of sterling silver and apart from the pain in the butt aspect of fitting it to his existing saya and tsuka I made sure it was work hardened by the time it was finished. That was about 5 years ago I think and that sword is still in weekly use with no problems. The original habaki fit properly and was flush against the machi as well as flush against the seppa. But it started to deform fairly quickly -- the blade it was on was an older blade that was pretty tired so I'm sure it flexed a lot. And the guy was a rather "robust" fella in his cutting style. Regardless, I can only report what I've experienced and what I was told. I will likely see Brian Tscernega at Florida and if isn't too busy maybe I'll bug him about this one too. I think I discussed it with him once probably about 3 years ago when I was asking about working the piece a bit after the soldering of the seam and machigane... But I honestly don't recall. So I'll ask him again if I get the chance. And on the martial arts end of things... Yeah, the Toyama Ryu fellas have had a profound influence on martial arts practice in the last 20-30 years. Increasingly so today. But remember that many koryu arts exist with a wide variety of styles and practices. And some forms of tameshigiri practice exist within many of them. The problem for some is that depending on when you were training you might see something like MJER or MSR iai styles as "representative". But frankly those styles are (in general) the more contemplative styles emphasizing solo kata without an emphasis on tameshigiri. As a matter of fact some sensei within some iai styles expressly forbid tameshigiri practice as being somehow disrespectful to the craft of the sword. But there are many styles out there from rough and tumble Jigen Ryu styles to the quieter, more subdued iai styles. I remember watching a Sekiguchi-Ryu (sp?) embu and noticing that their distinctive "Spin/Rap the sword" chiburi (don't have the name for it) really made their swords rattle. I wonder how many habaki they'd go through over time if the habaki was dead soft. And FWIW take a look at any sword used by a martial artist. Notice the impression of the habaki face into the seppa. Seppa are copper and will often take an imprint of the habaki. The deformation is sometime fairly significant. Now consider the greater mass of the habaki and how much more material there is to compress if it isn't work hardened. All interesting stuff. I'll ask Brian T about it next time I see him if I get the chance.

-

In terms of stress, if you look at blades in use by martial artists frequently the mune of the habaki tends to get somewhat compressed. In extreme cases the mune of the habaki "peels back" at the corners with a complete failure of the habaki. Blades flex within the mounts during difficult cuts through stuff. A light cut on light targets is basically insignificant. And with hard tameshigiri training there can be significant force felt transmitted down the blades into the hands. It is an extreme example but years ago Toshishiro Obata performed a kabuto-giri test. The cut was filmed with high speed cameras and the flexing of the blade was impossible to miss. That flexing on hard targets tends to push the mune machi into the face of the habaki. And I've seen well made habaki made by Japanese trained habaki shi on shinsakuto that have been distorting similarly by those who do a lot of cutting. Well made habaki on well made blades that were themselves professionally mounted in Japan. But vector diagrams... Sorry, not my area...

-

Just to add to the discussion... Copper work hardens. Meaning (in general terms) that when the piece is forged to shape the material develops internal stresses which increase the hardness level of the material. So while dead soft copper is pretty soft, if the habakishi is doing it right by the time the habaki is properly fit the material should be pretty tough. And while most seem to think that habaki take no stress, the reality is that *in use* they do take some. Obviously it will make no difference at all if the blade is just stored in shirasaya and lovingly admired under a candle. But as a functional tool the habaki needs to be relatively tough to withstand some of the stresses involved in usage. Work hardening gets you there with materials like copper. And since you can easily anneal the copper as you work (it gets hard fast) it is an easy material to work with (relatively) as you forge and you have a lot of control over how hard it gets by the time you're done.

-

I'll be there and I'll do just that. Thanks Guido!

-

No, not incorrectly, but that people use the terms with a different feel to them. It seems to me gendaito has taken on additional meaning as a sword "not from the 'real' times of Japanese sword" and as such aren't considered as highly regardless of the merit of individual blades.

-

Guido: As you know I'm a major fan of koshirae, themes, how they worked all the stuff together, etc. Would you happen to have a more complete set of photos of the koshirae for the Nakajima Rai piece? I really like the color selection in what I've seen so far and I'd love to see more.

-

FWIW I was trying to convey a feeling that seems to come with using the term gendaito vs. koto (or shinto, shinshinto, whatever). For some reason gendaito seems to carry a lot of extra baggage in common use. And as such it tends to be used differently even though technically the meaning is no different from the other terms in meaning. To some extent I think there is a sort of dismisal by many of the merits of gendai blades. Maybe due to the changes around Meiji and the profound effects on the sword world, maybe due to them being "too new", maybe due to them simply not being relevant in the same way any longer, but people tend to use the term gendaito a bit differently. Of course we're talking about common usage vs. defined meaning. And that's what I was (rather poorly) joking about. Some people will tend to dismiss gendaito with a wave of the hand (in my experience). "Oh, that's just a gendaito..." with the underlying implication intended that it isn't quite the same as blades from other periods. I also think lately there has been an increasing appreciation of some of the gendai smiths however (evidenced by prices some higher profile pieces have gone for recently) so maybe that is changing.

-

Yup... Feeble attempt at humor. And when you forget to put in the smileys or knowing winks oddly enough my less than well developed attempt at irony falls way short...

-

Ah, I try to say something stupid as a weak attempt at humor then forget to put in the smiley face to indicate as such. Insert one up above near the silly section about "shinto-to". I left out the smiley face to indicate a bad attempt at humor. Bottom line for me is that it is kinda interesting that we call these things "gendaito" but don't similarly use the single term to call koto blades "koto" in the same way. I'll often hear people describe their blade as a "gendaito" but then say "this is a shinto wakizashi". In other words you generally won't hear them say "this is a 'shinto'". We'll kinda skirt around with the usage but gendaito has a more common usage as a descriptor. Maybe because we're in it... Anyway, I just find it kinda interesting how the langauge ends up being used. And that is probably in part why people tend to debate this stuff more than they need to.

-

Just to add to the chorus... In talking with various folk in the world of swordsmithing *today* (i.e., modern swordsmiths, modern craftsmen, etc.) gendaito is pretty much the accepted term for anything traditionally made of traditional materials post shinshinto. The usage of shinsakuto is somewhat different and more refers to the "recency" of manufacture. So anything made (traditionally) post shinshinto is gendaito including made this very morning. But that one made this very morning would certainly also be a shinsakuto -- i.e., newly made sword. So a shinsakuto of the gendaito period of sword making. A newly made sword of the modern sword period. Of course I've heard a few prominent swordsmiths campaign for terms like shin-gendaito to refer to swords being made today that have made a rather large leap upwards in quality over 30 years ago (according to those people -- no need to debate that issue in this thread). I kinda doubt that's going to happen in any sort of general use, but it does point out that the term "gendai" has come to refer to a period of manufacture like koto or shinto or shinshinto. We're in that period now. So anything made today or in the last 100 years or so is a gendaito. I don't have much trouble with the terms. To me using "gendaito" is a bit of an interesting term. We use "Gendai-To" when we don't say "koto-to" or "shinto-to". Kinda interesting how language evolves. But it is really like saying "koto blade" or "shinto blade", etc. In other words referring to period of manufacture. Shinsakuto just means a newly made blade and is used really a different sort of word from the period descriptors and as has been pointed out would be correct in the Koto period if you happened to be there when it was made. So if I was standing there with Rai Kunitoshi accepting my new tanto it would be a shinsakuto when he handed it to me. (Ah, to dream...) It all makes sense to me... But then again I also get people arguing with me all the time about mekugi placement too... And I must say I agree with the NBTHK that sometimes some things take on waaaay too much importance in the larger scheme of things.

-

The link to the larger image contains an extra forward slash at the end of the link which makes it look for a directory rather than a file. The following is the correct link. http://www.nihonto.ca/kantei-l.jpg