-

Posts

978 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

4

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Steve Waszak

-

The second tsuba is not papered, but I believe this, too, is Shoami. Ko-Shoami? I can't be certain. It's primary feature is the pleasing crispness with which it has been carved. This effect is aided by its dimensions: while only 7 cm x 6.8 cm in size, it is also 5 mm thick, allowing a discernible depth to be achieved. This tsuba's motif is a collection of mon, sequenced among carved bamboo shoots at the cardinal positions. The condition is excellent, the iron punctuated by light tekkotsu scattered along the rim. A very elegant piece. Comes in a custom, fitted box. $375.00 plus shipping.

-

Up next from my friend's collection are two iron ji-sukashi pieces. The first is papered to "Myochin," though I suspect ko-Shoami might be the better attribution. This is a pretty dynamic sword guard. It measures 8 cm x 7.9 cm x 4 mm, and features a particularly expressive triple-tomoe motif. The iron is very good, presenting with a soft, natural patina and fine color. The lone hitsu-ana is very well formed, as is the massive seppa-dai. There are a few small tekkotsu in the rim, along with one very large one. These latter details combine to have me leaning more toward ko-Shoami than toward Myochin, though the fact that the shinsa team assigned a Myochin attribution to this tsuba may indicate something about its powerful presence. $400.00 plus shipping (PayPal friends and family preferred).

-

I'll be posting more this weekend, if not sooner!

-

Right there with you, Curran. This Juyo Rabbits tsuba has long been one of my absolute favorites, by any smith, and may be my #1 Hoan work (which is saying something). Hoan is not often mentioned in the same breath as Nobuiye, Kaneie, Myoju, and Matashichi, but certainly should be in my view, along with Yamakichibei, of course.

-

Up next from my friend's collection is an NBTHK-papered Heianjo-zogan iron tsuba. It features high-relief brass inlay depicting an active landscape scene, with dragons as a chief component. A lot going on in this composition. The hitsu-ana are irregularly shaped, and are plugged with what looks to be textured shakudo. The tsuba is in very good condition, and measures 7.6cm x 7.8cm x 4mm. $185.00 plus shipping.

-

Hi Florian, You make some good points here, especially about the Hoan smiths making their works for the Asano family (and perhaps for other high-ranking clans), but not for the masses. For some of the most highly regarded tsubako (e.g. Hoan, Nobuiye, Yamakichibei, and the Higo smiths), they were indeed retained by Buke families, and did not, as far as I know, make their works availably broadly and generally to the public in common commerce. I believe this was true of the Akao as well. As retained craftsmen, they received a stipend, thus removing the need (and, perhaps, the permission) to sell their tsuba to the masses. As for the 10-koku stipend the Shodai was provided by the Asano, while some may see this amount as meager, it may not actually be so. We may need more information about the particular circumstances involved, but if my understanding is correct, 1 koku of rice = the amount of rice required to feed one person for a year. The Shodai Hoan did not operate a "school," per se, with several students working in an atelier; rather, he had a son-in-law who became the Nidai Hoan, perhaps/probably not until the passing of the Shodai in 1613/1614. It is possible, if not probable, therefore, that the Shodai worked alone as a tsubako, with no actual "school" during his lifetime. So, 10 koku of rice, in being enough to feed ten people for a year, may have been more than adequate for the Shodai and his family.

-

Shibuichi(?) tanto tsuba featuring plovers over waves

Steve Waszak replied to Steve Waszak's topic in Tsuba

-

Last one for today... This is a little jewel of a tsuba, a tanto-sized piece done in what I believe is shibuich, with shakudo(?) and gold-leaf highlighting of the plovers flying about above the raging waves. The carving of the motif on this tsuba is sophisticated and very pleasing, with the plovers done in a high-relief, while the waves are rendered in a fluid and lively kebori. The tsuba measures 5.6 cm x 4.8 cm x 3 mm. It is kawari- gata (or kobushi-gata) in shape, with a rim-edge that curls up over the plate in various places around the tsuba. Seppa-zuri is clearly evident. A charming little sword guard. $275.00, plus shipping.

-

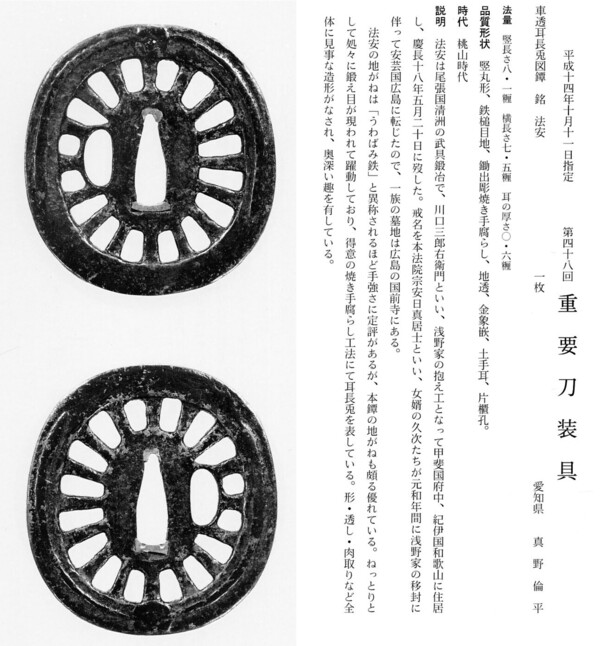

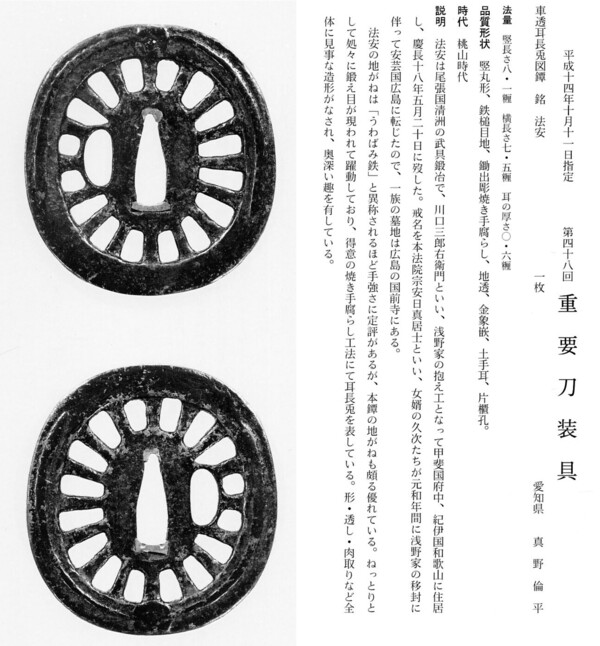

A little further looking around turned up the following, a Juyo Shodai Hoan tsuba with accompanying text translated by Markus Sesko: "Jūyō-kodōgu at the 48th jūyō shinsa held on October 11, 2002 kuruma-sukashi miminaga-usagi no zu tsuba (車透耳長兎図鐔) - Tsuba with cart wheel sukashi and a design of long-eared rabbits mei: Hōan (法安) Measurements Height 8.1 cm, width 7.5 cm, thickness at rim 0.6 cm Description Hinshitsu-keijō: tatemaru-gata, iron, tsuchime-ji, sukidashibori, yakite-kusarashi, ji-sukashi, kinzōgan, dote-mimi, one hitsu-ana Jidai: Momoyama period. Explanation: Hōan was an armor smith who lived in Kiyosu (清洲) in Owari province and whose real name was Kawaguchi Saburō'emon (川口三郎右衞門). When he became employed by the Asano (浅野) family, he also worked from Fuchū (府中) in Kai province and in Wakayama (和歌山) in Kii province. He died on the 20th day of the fifth month of Keichō 18 (慶長, 1613) and his posthumous Buddhist name is Honpō'in Sō'an Nisshin (本法院宗安日真). His son-in-law Hisatsugu (久次) moved during the Genna era (元和, 1615-1624) on the occasion of the transfer of the Asano to Hiroshima (広島) in Aki province where the local Kokuzenji (国前寺) came to facilitate henceforth the graves of all members of the Kawaguchi family. The powerful iron of Hōan works is praised by the rather uncommon term uwabami-gane (うわばみ鉄), which means lit. "large snake steel," and the steel of this tsuba is exceptionally well forge[d]. It has the characteristic "stickyness," shows a forging structure in places, and an etched (yakite-kusarashi) design of long-eared rabbits which was the strong point of this artist. Shape, openwork, and distribution of the niku are gorgeous, giving this tsuba a very profound appearance." So, it seems the Shodai's death date is actually quite specific (May 20th, 1613). It also appears that the Shodai's remains were moved to Kokuzenji Temple in Aki (Hiroshima), presumably after (or at the same time that) the Asano and Hoan Hisatsugu were transferred to Aki in 1619. Many thanks to Markus Sesko for the translation, and to Rayhan for his generous work in supplying these Juyo Zufo texts for our learning and appreciation.

-

Here are two iron sukashi tsuba from my friend's collection, one an early-Edo Owari piece featuring a motif of varying tomoe and crossbars. While there are a few subtle tekkotsu in the rim, the tsuba overall presents as migaki-ji, rather than tsuchime-ji, leading me to date the tsuba to the early-Edo Period, rather than to Momoyama times. However, the large size of the guard has me thinking this could be late-Momoyama. The more conservative call, though, would be early-Edo. Dimensions are 8.4 cm x 8.4 cm x 6 mm, so, a very large ji-sukashi piece. These dimensions, in conjunction with the lively motif of the tomoe set against the solidity of the heavy crossbars, make for a bold presentation. The hitsuana are classic Owari in shape and size for the period. $285.00 plus shipping (PayPal Friends and Family). The second tsuba is likely a Shoami work (or would be likely to be categorized this way). It features a matsukawabishi motif element set against a botanical element (I cannot make out what kind of leaves these are), both set within the "namako" shaped large sukashi openings on the right and the left. With the slightly rounded rim and the particular kind of sukashi openings (namako), I would not tag this as Owari. A notable feature of the tsuba is the large nakago-ana, measuring 2.8 cm from the top to the bottom of the ana. The tsuba overall measures 7.8 cm x 7.7cm x 4 mm. $185.00 plus shipping.

-

The 1645 death date for the Shodai (if accurate) invites many questions, such as where, then, the 1613/1614 date comes from, and why he would have been buried at Kokuzanji Temple, which is in Kii Province (Wakayama Prefecture), if he'd worked for the Asano from 1619-1645 in Aki Province (Hiroshima). The Shodai moved from Owari to Kai Province to work for the Asano daimyo in that province, and then to Kii Province, continuing to work for the Asano family after they had been transferred there (Asano Yukinaga, the daimyo of Kii, died in 1613). It would seem to be more logical to conclude that, having worked for the Asano family in Kii province, he passed away there some five to six years before the Asano were transferred to Aki in 1619, and was then buried in Kokuzanji Temple, than that he would have lived the last 26 years of his life in Aki, only to then have his remains be interred in Kokuzanji in Kii in 1645. It's also odd that it is specified that Hisatsugu (second generation Hoan) accompanied the Asano to Aki Province in 1619, while the Shodai is not mentioned as having also done so. I wonder if the 1645 date given for Hisatsugu having become the "head" of the family might allude to some "technical" detail regarding official titles. I am more inclined to regard the 1613/1614 death date for the Shodai as more likely to be accurate.

-

This piece is one of the highlights of my friend's collection. It is a 2nd- (or possibly 3rd-) generation Kanshiro Nishigaki sukashi tsuba, featuring a lively double tomoe-plus-kirimon motif. The shape is very appealing, I think, being that wonderfully peculiar aori-gata form that Kanshiro appeared to be quite fond of. A standout aspect of the guard is the fluid motion of the kirimon motif elements: they are not stiff and static (as they might be in a straight up-and-down posture, which is what we usually see); rather, they sweep from 6:00 on the dial toward 12:00, curving upwards through the forming of the blossoms, bringing a lot of vitality to the subject. They are juxtaposed against the negative spaces forming the double tomoe; this contrast only enhances the lively expression in this piece. I'm not even sure these are the best parts of the sword guard, though, as the metal is just superb. It is wonderfully finished, with a fine migaki-ji which nevertheless admits very subtle tsuchime. This is masterwork in tsuba finishing. The color is deep, the patina natural, clear, and glossy (as opposed to shiny). There is just the slightest hint of remaining kebori on the leaves of the kirimon. If this tsuba were larger (8 cm or more), the price would be MUCH higher for this superb tsuba. For those looking to move into higher levels of collecting, I would personally highly recommend this piece. Were I myself not so strictly focused on Owari works, I'd have bought this from my friend myself. Dimensions are 7.3 cm x 7.1 cm x 3.5mm. $1,650.00, plus shipping. PayPal Friends and Family preferred.

-

The triple tomoe tsuba with brass inlaid kikumon motif has SOLD.

-

Update: I spoke to the friend whom I'm helping to move some tsuba so he can reorganize his collecting focus, and we agreed that the asking prices on these two tsuba should come down. So, each is now offered at $325.00, plus shipping.

.thumb.jpg.fb1e72a0fd0e16461995f58269521ccd.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.be215dfd3f674c674113fecf759a8418.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.89f2726b63784cf0c636a7af69f57af1.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.65b5c7e994a0f3a7b7632dbc9caf34b2.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.9a1053778e1db061299abe7bf3717d91.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.e1719e5eeb5e38cea493fc1f4bdc1e1c.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.225c7dbf5a0a9c195841ba2de27e0599.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.776618a4b7e80e0b98ad019334fa6c80.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.2e294d757b596eca2a91f99274e73805.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.45443e636336c00c3f4bfa73f88f5e2d.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.3db4329a70a4fd2de60380bcc98fd42a.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.20dc5c0c579d0ca974f8087e84fcbb8a.jpg)

(1).thumb.jpg.8d60c1fbdb5d67c8f787c359b6f951b8.jpg)

(1).thumb.jpg.6b784863f34ab5ca8035a6549ed8495f.jpg)

(1).thumb.jpg.1671a6451e9174ebde07db8c62899aac.jpg)

(1).thumb.jpg.c1476d737b592707e2c484a9f8b7dfaa.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.44081aeedc5e38899d5b2871f38d5659.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.0336aaee9ffa23e374b249afd6d64793.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.99877740540edd8896c32f8157fccc6e.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.56e92fb9c264ea13d536d3d1b3cf6f3a.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.0b499c1f550837a1c450baa624a8a88b.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.db5ab74211a9704874b37f1856a0e4fc.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.5cbde4a73b4cef75bc6d0f1382744502.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.dffecb1b1ae2db5aef665cd7a6a9c176.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.0a2359680c898355da6eb67ace3741af.jpg)

(1).thumb.jpg.1412c4ea66c1c70e2e753b8f28495f84.jpg)

(1).thumb.jpg.48d94b4a2a1bf0deccf19e9a23a33eda.jpg)

(1).thumb.jpg.9cde543d104313d7630f3458ae03fcdb.jpg)

(1).thumb.jpg.3b9517da1d2de5f99f95b71be34a918a.jpg)

(1).thumb.jpg.dddce1c3411fee6bab4bf3903757a5d6.jpg)

(1).thumb.jpg.53e5d910d4bce9f3ada98be884276061.jpg)

(1).thumb.jpg.014711dbf411836712eda24e9a15e5cb.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.ee7c96cd57aec114ae2cbb241ac33358.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.28d8eda63f0f2c25f7141a7f23f30aa3.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.0955cb7a888dba4f71742267c923b02c.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.7db473f5ba4b88d33469e4adcd3d7da9.jpg)