-

Posts

976 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

4

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Steve Waszak

-

Hi Henry, A few things... First, the "Saotome" tsuba in question was/is not mine. It was presented for sale, with the paper attributing it to Saotome. Had it been my tsuba, I certainly would not have submitted it, as there would have been zero need to: it is 100% a Yamakichibei. Granted, the guard is in poor condition, and someone has messed with the hitsu-ana in a bad way, but it is Yamakichibei (not one of the two men that most scholars recognize as the only two working in the Momoyama Period, but one of the two others that these scholars refuse to recognize because it would upset the catechism). As I have mentioned, it is signed (the significantly abraded condition of the mei does make it hard to see, I realize...), so trying to "understand" a Saotome call for this piece would be futile (outside of something akin to morbid curiosity). I also take some umbrage to your characterizing my resistance to accepting such papers as "Nah... don't think so, coz I don't think so." I have provided extremely specific, precise reasons why a call to Saotome makes no sense. It is ironic that you would characterize my response in this way, given that shinsa teams effectively expect us all to accept their conclusions for just those reasons: "We think so, coz we think so." How often do we see shinsa teams offer detailed, carefully delineated reasons for arriving at their conclusions for tosogu? Further, I think it is inaccurate and rather curious, frankly, that you say (concerning your Nobuie guard) that "the lack of interest that the members who opposed the NTHK (NPO) conclusion showed to this composition, to me, says a lot..." Pete and I both spent no small amount of time considering your tsuba with care. I made the point, more than once, that to attempt to judge the authenticity of the work, especially the iron and the workmanship, from photos alone was fraught with difficulty, and so backed away from attempting to do so. On this score, it is a bit disingenuous of you to note that you have consulted with others in Japan about the tsuba: they have seen the guard in hand; this makes a huge difference. All that Pete and I could go on with some degree of confidence, therefore, was the mei. I spent considerable time detailing the reservations I had about the authenticity of the mei, essentially echoing Pete's observations. I stand by my reservations of the way the mei is done, for the reasons I detailed earlier. I said in response to this oshigata you've provided that there was not enough to go on from this reproduced oshigata to draw any firm conclusions. The initial two strokes of the "Nobu" ji are missing, so one cannot judge from this. Further, those missing horizontal strokes on the left side of the "ie" ji are very worrisome. They should not be absent. In any event, one of the comments I'd made to you, Henry, about your identifying this as a futoji-mei signature was that, if anything, it would certainly be a hanare-mei, were it genuine. It has virtually none of the identifying features that would produce a futoji-mei call for this signature. And as for its being a legit hanare-mei, well, as I stated in the earlier thread on this piece, there are three or four aspects to the way the mei is rendered, especially the "ie" part, that are problematic. One of these by itself might be shrugged off; but when multiples emerge, this, as I say, is worrisome. I also stressed in my posts before that I sincerely hoped I was wrong, and I may indeed be. I would much prefer that your tsuba was authentic. But instead of automatically assuming that the shinsa team "must be correct" and that therefore there must be "gaps in the knowledge" of those that find the shinsa conclusions dubious, you should be considering the actual points being raised to support the resistance to the shinsa results, and analyzing these yourself. I notice that you didn't respond to a single one of these highly-detailed points that Pete and I raised. He and I didn't make these up out of thin air. Why didn't you engage in a discussion about these points, Henry? There is simply far too much deferring to shinsa teams as unimpeachable authorities occurring. There is no intrinsic Japanese trait that makes their analytical skills any more finely honed than ours. So let me turn the question back around onto you, Henry: what exactly in the shinsa team's judgment that the "Saotome" tsuba in question is, in fact, Saotome allows them to conclude this? Precisely what evidence supports this? Steve

-

Lee, Well there are a few things to consider here... First (as your qualifier suggests), arriving at confident judgments of iron character from photos is notoriously challenging; my providing of the photos of other pieces is therefore not so much about inviting careful comparisons of the various pieces' iron qualities as it is about offering tsuba to compare the mei and motif-work of. Further, the tsuba in question would seem pretty clearly to have significant condition issues (to put it mildly). The hitsu-ana would likewise appear to have been tampered with (also to put it mildly). As to the rendering of the sukashi elements, again, a hand-held examination would afford more confident conclusions. As to this being an utsushi of Yamakichibei work, it could be, but I strongly doubt it. However, having said that, I need to emphasize that I do not subscribe to the current view which holds that there were only two early (Momoyama) Yamakichibei tsubako. I believe there were at least four, probably five, of which the man who made this piece was one. Utsushi of Yamakichibei work is more or less limited to 19th-century copies after the time of "Sakura" Yamakichibei (latter 17th century), who did do some utsushi work, mostly in the vogue of the "nidai" Yamakichibei. When one views the 19th-century Yamakichibei utsushi, one does see very different treatment and appearance of the iron itself when compared to authentic Momoyama/early-Edo pieces. In any event, Lee, the main point of my original post was that the tsuba in question is not Saotome, yet it received an NBTHK paper to Saotome. Anyway, I fear that I am... Cheers, Steve

-

Yes, I can see where I come off as rather stubbornly insistent... But I suppose it would be helpful, as John said earlier in this thread, if the various shinsa teams were (more) transparent and generous with their assessment processes. Doing so would not only make their judgements more trustworthy/dependable, but would afford a terrific learning opportunity for us poor, lost students... One wonders why such "generosity" is not made available, especially given the prices paid for papers... I know I would love to see the explanation offered up for determining the tsuba in question to be Saotome... Tu amigo vano, Esteban

-

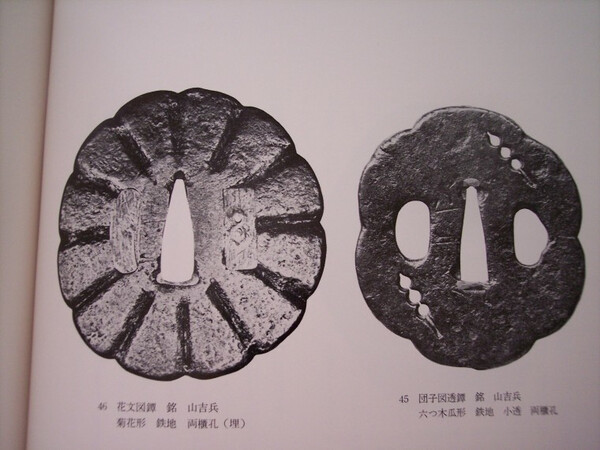

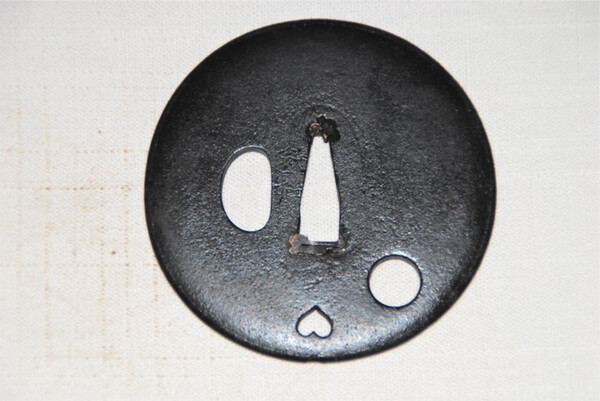

You need to look a little more carefully, amigo... There are certainly the clear remnants of the "bei" character from the Yamakichibei mei present in the "Saotome" guard, right between the "e" kana character and the left bottom corner of the nakago-ana. Further, the subject in the upper right of the tsuba references skewered dumplings, which as a motif has very tight associations with Oda Nobunaga, whose home province of Owari the Yamakichibei tsubako lived and worked in as well. The Yamakichibei tsubako are known to have reproduced this particular motif with some frequency (see photos below). Scholar John Dower, writing in The Elements of Japanese Design, notes that "..."...Oda Nobunaga [織田信長 or おだのぶなが - 1534-82], Japan's great sixteenth-century unifier...wished to see the severed heads of his enemies skewered like dumplings on a spit." (Dower, 110) Nobunaga's well known fondness for dumplings even resulted in a nickname for this particular food: uesama dango---"his highness's dumplings." (http://www.busho-aichi.jp/english/index.html) This design motif alluding to "Nobunaga's dumplings" is reproduced in the first image below. That there is a firm, concrete connection between Yamakichibei tsuba and the use of this motif is thus clear enough, but on top of this, I know of no other group or individual tsubako who uses this particular design, certainly not the Saotome. And on top of that, the use of (what looks to be) the "e" kana (katakana) is another practice virtually unique to Yamakichibei tsubako (see photo below). When one combines this knowlege of use of "trademark" motifs, with the yakite treatment evident on the tsuba in question, AND the remnant "bei" ji visible just at the lower left of the nakago-ana, it becomes abundantly clear that this is a Yamakichibei guard, and not Saotome. Yet it is papered Saotome. Still chalk and cheese...?

-

Seems it's time to "demonstrate a...gap in my knowledge by contradicting one of the main sword groups..." Not too long ago, the first tsuba pictured here received NBTHK papers to Saotome. For many, such papers with such an attribution would put an end to any speculation as to who/what group may have made the work in question, as the NBTHK had "decided" the issue. The fact is that this tsuba was certainly not made by any tsubako of the Saotome group. It is positively a Yamakichibei tsuba. Not only is it a Yamakichibei tsuba, but the specific Yamakichibei tsubako who made it is identifiable. The style, workmanship, motif, and remnant mei(!) all confirm this "attribution." I am providing photos of two other Yamakichibei guards, made by the same tsubako as the tsuba in question, for reference. As I have said many times in the past, I don't necessarily fault the NBTHK for making mistakes, even ones as serious as this. The far greater fault is to be found in those who uncritically and unreservedly accept any and every NBTHK/NTHK judgment as inarguable fact. Because the inescapable conclusion, drawn from the egregious NBTHK mistake in stating this tsuba to be Saotome, is that one can never know when the NBTHK (or other "main sword group") will be in error, which means that having full and unqualified confidence in papers is necessarily sheer folly. And all of the above is besides the murky issue of the politics of shinsa/papering, which only further cloud the reliability of papers... This is not to say that there is never any circumstance in which it is reasonable to seek papers for tosogu; however, I would argue that even in such a case, whatever judgment is rendered is only a starting point in ascertaining the actual origins/maker of the piece in question. Steve

-

Kanzan Sato - Kodai Yamakichibei - Tsuba Attribution

Steve Waszak replied to Robert Mormile's topic in Translation Assistance

Hi Robert, Well, according to Okamoto, the "yon-dai" would specifically refer to an individual smith, the "fourth generation." Some may say that this fourth generation smith would be part of a "ko-dai group," in that any post-Momoyama-to-very-early-Edo Yamakichibei smith would be a "later generation" than those smiths working in the early 17th century. I think your locating of this "yon-dai" in the second half of the Edo period is likely to be accurate, specifically in the 19th century, when the revivalist spirit informed the zeitgeist of the times... Cheers, Steve -

Kanzan Sato - Kodai Yamakichibei - Tsuba Attribution

Steve Waszak replied to Robert Mormile's topic in Translation Assistance

Hi Robert, Okamoto, author of Owari To Mikawa No Tanko (Tsuba Smiths of Owari and Mikawa Provinces) would identify this tsuba specifically as made by the "yon-dai." This assumes that one accepts the traditional understanding of generations of Yamakichibei tsubako. While the "yon-dai" was likely a later smith (i.e. not Momoyama or very early Edo), it is, as far as I know, simply convention that he is seen as the fourth-generation Yamakichibei. I for one am quite doubtful about this understanding of this "school." Cheers, Steve -

Many thanks, Ford, for these very interesting photos and descriptions of the process. Looking forward to seeing more... Cheers, Steve

-

Exactly right. :D I'm always amazed at how relatively rarely such broader and deeper cultural connections are investigated with regard to nihonto and tosogu study. Cheers, Steve

-

Pete's post above, in particular his contention that "to understand Momoyama high-end samurai culture you need to understand wabi cha" is right on the money. I couldn't agree more. I might extend this to the "Oribe Tea" immediately following Rikyu in the 1590s as well. The Tea sensibility suffusing buke culture in the Momoyama Period is intimately connected to the aesthetics of high-level tsuba from that time and extending well into the 17th century, particularly in Owari and Higo. I firmly believe that attempting to study and appreciate iron tsuba from this period without also studying Tea and its aesthetics is nearly pointless. Cheers, Steve

-

lol... We'd have been scuffling for it, Pete! I actually can't believe it sold so cheaply. The tsuba is much better than that price, IMHO... Cheers, Steve

-

Hi David, That tsuba from page 181 in Sasano's first book, a piece he labels "shodai," is absolutely no-doubt "nidai." Even beyond the fact that it has since gone juyo as "nidai Yamakichibei," it is so obviously and iconically nidai in sensibility, design, style, and execution that it is frankly astonishing that Sasano could have thought it was "shodai" work. A very odd attribution. Pictured below is the tsuba in question. Cheers, Steve

-

Hi David, While this may be the best Yamakichibei to come out of Skip's collection (so far), and while it does appear to be a fine guard and a period piece (Momoyama to early-Edo), it is not a shodai work, in my opinion. I can see at least three things about it immediately which allow for this conclusion, but hand-held inspection would likely yield more. Again, I'm not disparaging the tsuba: I think it's a good piece (again, just going by the photos), but a workshop piece created in the early 17th-century Yamakichibei atelier. It's also possible that it is a much later work (i.e. 19th-century revival), but my initial thoughts are as I describe them here. Cheers, Steve

-

Help on an umimatsu netsuke

Steve Waszak replied to Bernard's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Umimatsu = "sea pine" = fossilized coral. Cheers, Steve -

Right. Thanks, Grey. Fair enough. Cheers, Steve

-

Maybe if we all make enough of a racket, we can push Grey into some Black Friday deals... Cheers, Steve

-

I would agree with what Mark says here... And I agree, too, that this second bowl is not a modern work. A nice piece for sure. Cheers, Steve

-

Help on an umimatsu netsuke

Steve Waszak replied to Bernard's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

PM sent. -

Yes, many thanks to Markus and Pete... Much appreciated.

-

Example of kusarashi yakite here on this tsuba: the perimeter of the sukashi element to the right of the nakago-ana gives evidence of such a treatment, I believe. Cheers, Steve

-

Thanks, Uwe. Much appreciated. Unfortunately, I don't have access to the tsuba to try to post a better photo of the mei. Hopefully, your efforts here will help a lot. Thanks again. Cheers, Steve

-

Greetings gentlemen, I would very much appreciate assistance in reading the mei on this tsuba. The second ji may read "Nobu"(?), but I cannot make it out for sure. The first ji I cannot manage to read clearly at all. Thanks for any help... Cheers, Steve

-

Some really fine posts in this thread. Thanks especially to Kunitaro, Pete, and Chris... Pete, any further info on that kozuka? Enjoying this thread. Thanks, Veli, for raising the question(s). Cheers, Steve

-

Hi Ford, Isn't it the case that much, if not all of the history of Nobuiye and his name and progeny that you reference in your latest post is connected with the assumption that the great tsubako is the same man as the armorer Myochin Nobuiye? It seems to me that it has been fairly well established that the armorer and the tsubako were two different men, with the armorer working a generation or two earlier than the tsubako. I am with you, Ford, in remaining skeptical about the association between Takeda Harunobu and the tsubako Nobuiye, and about the notion that the latter received the Nobu ji in his name from Harunobu. If it is the case that Nobuiye was an Owari man, or even if he moved from Kyoto or Mino to Owari, his contact with Shingen/Harunobu would have to have been limited, no? I am not aware of the Takeda leader spending a lot of time in these areas. So how would Nobuiye have even been in contact with Harunobu? As for all the other names he is supposed to have signed with, has any of us ever seen a single tsuba anywhere with any of these mei (I mean a piece which stylistically and otherwise could be recognized as Nobuiye-esque work)? I don't believe I ever have. One interesting implication, too, about all this historical data is that if your idea, Ford, that Nobuiye guards were initially made and regarded as humble artefacts is correct, it would seem unlikely that such data/records about this tsubako would have been kept. Of course, for the armorer Nobuiye we might expect so (whether the data/records are invented or not), but for a "humble tsubako," not so much. Naturally, to invent such a history much later (Soken Kisho) would not have been a problem, but doing so 200 years after Nobuiye's time would seem to, um, make such a history suspect. Your thinking on Sasano mirrors mine, Ford. While I appreciate his passion and enthusiasm, his advice for identifying the genuine article is not exactly helpful in any concrete way. The quote you chose at the end of your post is a perfect illustration, and represents a frustration I have long had with his writing: an abundance of entirely subjective, unquantifiable, effusive adjectives, with little in the way of objective criteria to balance the subjective. It's too bad, because I sense a deeper, more accessible (via objective criteria) knowledge is there, but he was unable, or unwilling, to express it. Do you ever get the impression that the gods have simply ordained that Nobuiye shall remain a perpetual mystery? Cheers, Steve