-

Posts

978 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

4

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Steve Waszak

-

Ed, I definitely hear what you're saying. Having a few of these on the property helps with my peace of mind.

-

Ahhh... Thanks, Ed. Some great pieces there.

-

-

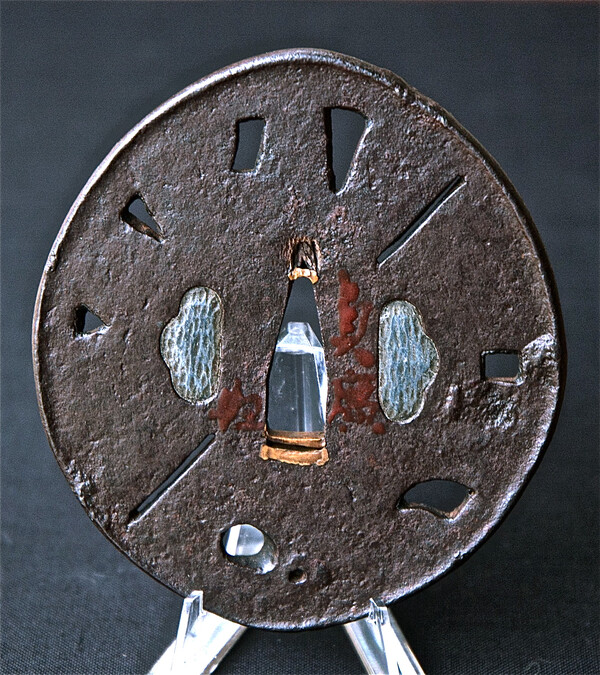

Steel tsuba. 8.9cm. Uchikaeshi mimi. Otafuku-mokkogata. Owari Province. Momoyama Period. Interesting tsuba: though it has both NTHK papers and a shumei to Sadahiro (referring, I believe, to Owari Sadahiro, Keicho era, Momoyama Period), there is, on the left side of the seppa-dai on the omote, the remnant mei of the nidai Nobuiye. It has been abraded significantly, to the point that, in most light and in most angles of light, it is gone. But in the right light, at the right angle, the characteristics strokes forming the "Futoji-mei" Nobuiye (nidai) signature can be seen. It is, unfortunately, extremely difficult to capture this "ghost mei" in photos.

-

-

Okay. Thanks, Jim.

-

Would this by any chance include the Akao group? I'm thinking probably not, but...

-

Can Someone Help Explaining The Following Price/tsuba

Steve Waszak replied to Fuuten's topic in Tosogu

Axel, Haki is a Japanese term I have seen translated as "power," or "unbridled spirit." It is used (among other applications, I imagine) to describe works that are particularly expressive in terms of boldness. Early (pre-Edo) Owari tsuba, more than most, possess great haki. They are often large, with heavy, wide rims and sukashi walls, restrained tekkotsu, and bold, direct, symmetrical designs, exuding potent martial confidence. They are usually not "poetic" in the way Kyo-sukashi and Akasaka tsuba can be (often to the point of mawkishness, I think, but that's just me). Their forging and steel quality in general is said to be very high. Sasano called Owari sukashi tsuba the ultimate when it comes to guards expressing martial power and spirit in the eyes of the bushi of the time. And it is true, too, in my experience, that when one sees a great Owari tsuba from this period and of this size---in person---the effect is memorable in a way few other tsuba can match. For lack of a better term, they "pop" with boldness, making other tsuba around them lifeless and dull by comparison. Again, this effect may be hard to experience just from photos. I would guess that the tsuba in question possesses significant haki, and that, in person, it dominates the space around it. Personally, I find the piece to be a bit too busy (I prefer a sparer design), but yeah, old, large, haki-infused Owari guards in great condition (terrific patina) can command such prices. They are rather rare. Cheers, Steve -

Thanks for the heads-up on this, Pete. Some very nice pieces there for sure. Looks like your fave is already spoken for? Cheers, Steve

-

Hi Ron, You're in luck: Grey has a copy currently. I have this book. Many oshigata of great Nobuiye Tsuba. Cheers, Steve

-

Hi Curran, I believe John is referring to the group of tsuba recovered from the shipwreck of the Spanish vessel, the San Diego, which went down in the middle of the Momoyama Period, around 1600 if I recall correctly... Cheers, Steve

-

Securing a collection in the UK

Steve Waszak replied to Kronos's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

I find two or three mastiffs to be a remarkably effective deterrent to thieves. My dogs, plus a fire-resistant safe, is about all I need... Cheers, Steve -

Hi Ed, Many thanks for posting these... All are very appealing. To my eye, and from having studied Momoyama era Oribe ware a bit, the two kogo appear most likely to be period. The chaire is a mayyybe, while the others look revivalist (i.e. 19th-century) or later. The publication, Turning Point: Oribe and the Arts of Sixteenth Century Japan Met Publications, 2003) is an invaluable book for those interested in Momoyama Period pottery, especially that connected with Tea, and even more so as concerns Furuta Oribe and the ware(s) that he is so intimately associated with. In particular, there is a valuable set of images---some of Momoyama era kuro-Oribe pieces, and then of 19th-century revivalist pieces---for comparison purposes. Highly recommended. Cheers, Steve

-

Pete's idea is the way to go. I certainly would be interested in contributing to a translation project for Markus on this book. The problem with having a Japanese person read it for you, Grev, is that unless this person has some good knowledge of the terminology/concepts attached to tsuba study, he or she may have some difficulty in communicating that terminology/those concepts with precision and clarity. Cheers, Steve

-

Hi Ed, Beautiful chawan. Thanks for posting the images. You mentioned Oribe and kuro-Oribe in your post, and having a number of works of these types. Are the pieces you have period (i.e. Momoyama), or later works? Might you have any photos you could share of these? Cheers, Steve

-

Hi Junichi, By "privileged," I am not referencing economic status or a culture of affluence. I am speaking of the term/concept of "art" itself as being of an exalted status, i.e. something termed "real art" versus being seen as "only" craft, or as "only" decoration. Cheers, Steve

-

The real question is why the term "art" is so privileged. To inquire whether a given work is "real art" is to reinforce and sustain "art" as a privileged thing/notion. It may be worth considering what's at stake in the question itself... Cheers, Steve

-

:clap: Well done, Brian. There really is no valid argument against such a forum here on NMB: As Kevin and Thomas say, it is all interrelated. In fact, I would suggest that to study nihonto and tosogu without larger cultural contexts (as may be represented by various other art/craft forms) is likely to yield less convincing conclusions. Thanks for adding this forum, Brian. Cheers, Steve

-

Thanks, Ian. Your thoughts are much appreciated. Cheers, Steve

-

Many thanks for this, Ian. Very helpful, actually. Does it make sense to speculate that, as Sengoku Jidai aggressions wound down over the course of the Momoyama years, "no-name" armorers who showed special skill in finer metal work would (be allowed to) transfer their efforts to tsuba and away from armor production? I guess I'm just wondering what the dynamics were that would see tsubako of the caliber of Yamakichibei and Hoan emerge from the anonymity of armor-making. Both of these smiths are thought to have lived and worked in Kiyosu, Owari (along with Nobuiye). Might there have been some special circumstance that could explain how these guys evolved into tsubako, even tsubako who signed their work (among the very first smiths to sign tsuba)? Just thinking out loud here... Cheers, Steve

-

Great to see so much Iga-yaki here! Brian, it appears we need a ceramics forum... Cheers, Steve P.S. Chris, that Iga tokkuri is especially appealing. Thanks for sharing!

-

This post is really directed at the "armor guys" here... In various reference works, the Momoyama Owari tsubako Yamasaka Kichibei Shigenori and Kawaguchi Saburoemon Noriyasu ("Hoan" is the name he is better known by in tsuba) are mentioned as armorers working for Oda Nobunaga. I'm wondering if any of the armor guys here might have a reference publication which either lists or illustrates an armor or kabuto work by one or both of these smiths. It is unlikely, I realize, but on seeing such mentions of these smiths so specifically as armorers for Nobunaga, I am curious if there might be any publications that note such information. Thanks. Cheers, Steve

-

Brian, Would definitely appreciate a pottery/ceramics category here. As Christian says, some of us are as devoted to yakimono as we are to nihonto/tosogu... Cheers, Steve

-

lol... Sorry, that "yes" was meant as a response to Philip!

-

Yes.