-

Posts

978 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

4

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Steve Waszak

-

Hi Chris, Actually, I'd recommend Sasano's Early Japanese Sword Guards: Sukashi Tsuba as the best introductory text for appreciation of early iron guards. But I'd be more than happy to elaborate in detail on the merits of early iron tsuba... Please feel free to email me at stevewaszak@cox.net. We can get into lots of specifics. If necessary, we can arrange a phone call. Happy to help if I can... Steve

-

And, uh... What ever happened to the Buttweiler School pieces? Still floating around out there...with their papers? Wonder what else he made...

-

Thanks for this reminder, Pete: I do need to get a copy of this book. Don't know why I haven't up to now... I have had a few twisting, tortured experiences along the way! But none to top yours here. Alas, I haven't your resolve, Pete: I have fallen into the Pandora's box of ceramics, too... Hopeless and helpless I am...

-

Pete, Great story, congratulations on your "re-find," and thanks for posting the video. Really helps to bring these menuki to life!

-

Hi Ford, Sounds good, Ford. I look forward to that day very much... God knows what might come out of our mouths once the sake is flowing! Cheers, Steve

-

Hi Ford, Agree with pretty much all of what you say here except, perhaps, the bit concerning the hitsu-ana (a relatively minor point ). Your thoughts about the first tsuba being a better example of its type than the Kanayama is of its type (Kanayama) I wouldn't necessarily disagree with, either, though outside of the first one's being called a "tokei" tsuba, I'm not sure what type it is. I certainly concur that there are much better Kanayama guards than this one, and the price this piece carries ($2,500) is about the upper limit that it could/should command, in my view. It's a good Kanayama, but "good" is about all. Oh, and I need to add that if I left the impression that I thought both of these were Kanayama works, apologies: the first is not, of course, a Kanayama tsuba, and I never meant to suggest that I thought it was. And you're quite right, too, in saying that the two are not really comparable in that they each pursue different aesthetic goals (the shared motif is not really a point that should/needs to be compared). But if I were a bushi in need of a new guard for my koshirae, and was enamored with the "tokei" look, I'd definitely be choosing the Kanayama over the other, IF cost were not an obstacle. I can certainly accept the argument that the first tsuba represents a better value for the money, especially if a bit of TLC were applied, than the Kanayama would (for its type). I will hold that the Kanayama is the stronger tsuba if we are simply asking which tsuba I'd rather own, but when the question is presented as you do (which is the better buy for the money?), I don't see any discord in our thoughts... Cheers, Steve

-

A few thoughts to convey in response... First, as to what I mean by "stiff, dry, and lacking in vibrancy," what I'm trying to say is that, sometimes, we encounter pieces that lack subtlety in the fluidity of their lines (here I do not only mean the relatively two-dimensional lines of the top-down view of the tsuba's "face," but also the niku moving from seppa-dai to mimi, and "traveling" across the plate). The first tsuba you present appears to me to be lacking in this fluidity: there is little to no sensuousness to the form. It is rigid. Of course, this is in the eye of the beholder, so one's mileage may vary... The tsuba also presents (in this single photo) as lacking depth to any patina it may have; it lacks the "wetness" so prized among many old-iron tsuba connoisseurs. Again, I qualify this statement due to the fact that we are viewing these pieces through photos only, and in the case of the first one, a single rather poor image. It may be that, in hand, it does indeed have a deeper, richer patina than it appears to here. When a tsuba lacks both the "life" of a wet patina and is also lacking in fluidity/sensuousness of the forms that comprise it, then to me, it lacks vibrancy therefore. Tsuba #1 is thus dull, insipid, DOA... Ford, Oh come now... You know as well as I do that actually working with metal has nothing at all to do with whether one is "beguiled" by "lumpy bits in iron." Our response to such "bits" is based on aesthetic sensibilities, and is not related to experience at the bench. Further, whether there may be any certainty in how tekkotsu "may be explained or described" again has zero to do with appreciating their effect. And your separation of aesthetic value and market psychology is something of a false dichotomy: if one (or the market) values tekkotsu aesthetically, and enough sympathize with such a valuation, then the market will respond. Perhaps I'm not understanding what you mean by the distinction you're making exactly... As for your comment about tulips and the like, if your point is simply that tastes change, and that there is no accounting for taste (and the [market] values/valuations that accompany shifts in taste), well...yeah. There is no fixed and objective, intrinsic superiority of one form or another, whether in tsuba art or any other. What one considers superior to another depends on argument, not on fact. So I'm not quite sure what you meant to accomplish by including this comment. I find your thoughts as concerns tsuba #2 quite intriguing. As we all know, one cannot accurately assess surface presentation of tsuba via photos, so the statement you make about its state of preservation is curious and perplexing. Then, your qualifier---"apart from some obvious lumpiness in the rim"---in assessing the quality of the iron is frankly odd: you select out THE dominant aesthetic property of Kanayama guards and then evaluate the rest. I guess I might say that, apart from the engine, transmission, suspension, and chassis design, there isn't much special about ferraris. Sheesh. Further, by comparison, the metal of tsuba #1 appears (in the photo) to be utterly lacking in character, unless one finds rust patches to be "character building." And there is nothing at all "awkward and stiff" about the hitsu in tsuba #2---in fact, their placement so close to the edge of the plate creates a liveliness that, again, tsuba #1 wholly lacks. The hitsu-ana placement in tsuba #2 presents as carefully considered; by contrast, the hitsu-ana in tsuba #1 come across as rote, by-the-book, mindless. The price of this tsuba is fine. $2,500 for a good tsuba is nothing. Juyo-level Kanayama are $10K-plus. This piece isn't juyo, obviously, nor even TBH; but it is a good Momoyama Period Kanayama guard. There are not a lot of these around. If anyone thinks that a superb-quality Kanayama tsuba can be had for $2,500, he had better reconsider what counts as superb. For maybe the fifth time, I'll say that without seeing the tsuba in hand, I would reserve any sort of final judgment. But it is a superior rendering of the motif to that seen in tsuba #1, at least in the features I would value. Finally, oh I wish it were so that such "flash patination" could work such wonders. I have yet to see anything approaching a convincing patina in quick-fix (and even the vast [VAST] majority of slow-fix) cases. When one has seen deep, old patinas on fine iron, there is nothing that can compare. I am not suggesting here that tsuba #2 has such a patina; I rather doubt it, frankly (though again, I have only photos to look at). In any event, and in the end, it really boils down mostly to taste and what we find appealing. I personally loathe Edo Kinko as hopelessly trite, mawkish, saccharine (most of it), but that says everything about me, and virtually nothing about the pieces themselves. I think all we can do is try to assess how well an aimed-for aesthetic expression achieves those aims vis-a-vis others that also target that expression. And to my eye, tsuba #2 easily out-does tsuba #1, and it is a good, though not great, example of Kanayama sensibilities. Cheers, Steve

-

An interesting thread. Personally, I see #2 as far superior to #1. #2---a Momoyama Kanayama guard---is peppered with strong tekkotsu all over the rim (a highly desirable feature for those who like the Tea aesthetic), and, at 6mm thick, is a substantial tsuba, even at its otherwise smaller dimensions. It also appears to have a much better patina, though of course, such judgments always come with a caveat when they are made via photos, only. #1 to me appears stiff, dry, lacking the vibrancy that #2 has. I'm not a fan of the "tokei" motif, personally, but setting that aside, I can see why #2 would be valued at several times what #1 would be. Wakeidou's price (280,000 yen) actually makes sense to me ($5,000+ would not, however). Cheers, Steve

-

Shocking news. Very, very sad. Rest in peace, Thierry.

-

Umetada Myoju Tsuba

Steve Waszak replied to Thierry BERNARD's topic in Auctions and Online Sales or Sellers

That mei was scratched in the day before yesterday...with a paperclip. -

Thanks for that, Pete. Excellent.

-

Guido, My comment on objectivity really was made with a wink: even in the endeavor of objectivity with regard to technical skills, all one can arguably achieve is to observe and identify. As soon as one begins to evaluate, objectivity must fade away. What is fascinating to me, though, is that, given how personal one's response to art is, we might expect no such thing as consensus in what constitutes "the greatest" art/artist. Ford, I definitely take your point regarding the impact of "Sensei-ism" in Japanese culture, but consensus on the greatness of certain artists and/or works is not limited to Japan, of course, so the phenomenon of Sensei-ism can't explain it completely. How is it that so many agree that Hon'ami Koetsu's "Fuji-san" chawan is among the greatest ceramic works in history? I mean, there have been millions of tea bowls made; why does that one, particularly, rise to the top? Of course, we could go straight to Leonardo's Mona Lisa here, too. Among tsuba, what exactly accounts for Kaneie and Nobuiye having been "recognized" as the two greatest names in tsuba? Why those two? Why not three, or four? Or only one? In other words, precisely what separates those two names from all the rest? I fear, though, that I have steered the discussion away from Sebastien's inquiry again. Sorry. Back to that, then. Sebastien, it looks like three publications have been mentioned: 1. Shinsen Kinko Meikan. 2. Noda Takaaki's Banzuke (Tohken Tsuba Kagami). 3. Kokusai Tosogu Kai (KTK) 2016 catalogue (Nick Nakamura's rankings). I have heard that Tsuneishi Hideaki's Tsuba no Kantei to Kansho also presents a sort of ranking list, but I haven't had the book in hand yet, so I can't be sure. Any else know of others? Cheers, Steve

-

Interesting stuff, guys, but I think Sebastien is really just asking about publications (whether in print or online) that identify first-rank tsuba artists, second-rank, third-rank, and so on. Does anyone know of any other publications that make such identifications? I believe the 2016 KTK catalogue includes such a ranking list toward the back, though having seen it, I find aspects of it problematic. It is, incidentally, heavily weighted toward kinko. And as I hinted at in an earlier post in this thread, knowing the specific criteria by which high(er) rankings are achieved would be useful, to say the least, even more so if there were some objectivity involved (but that might be asking too much... ). Cheers, Steve

-

Just as an example of potential discrepancies: Not having the Shinsen Kinko Meikan, I can't reference this myself, but Noda Takaaki in his Banzuke essentially has an equal ranking for Hayashi Matashichi and Owari (shodai, I presume) Sadahiro. He also has an equal ranking for Yamakichibei and Choshu Mitsutsune. I find both of these surprising, personally. In the former case, not because of any significant qualitative differences between the two, but because Sadahiro does not seem much appreciated in tsuba circles these days (certainly not in the same way Matashichi is revered). And in the latter case, my surprise comes from what I see as a rather wide gulf between the strength of artistic expression (what Kokubo calls "haki," described as "power, ambition, unbridled spirit") in Yamakichibei guards, on the one hand, and (the lack thereof) in any Choshu work, on the other. Choshu tsuba, for me, are simply much too "pretty" to possess or express haki. Noda has his top two tsubako (this is for steel tsuba, not kinko) as Nobuiye and Kaneie as a pair, followed by Yamakichibei and Choshu Mitsutsune, followed by Sadahiro and Matashichi, also in pairs. So Noda is saying that these are the top six smiths working in iron/steel whose names are known. As suggested above, I am amazed at Mitsutsune's ranking, especially given that Kawaguchi Hoan is nowhere to be found among the top six. Who does Kokubo have, then, in his top six (or top ranks)? I realize that such lists are of course quite subjective, but they can still be interesting and suggestive, too. And given that value/financial considerations are often attached (if only loosely and informally), they are not entirely unworthy of our attention. Cheers, Steve

-

Thanks, Guido. I'm not surprised. It would be interesting to compare Kokubo's rankings with Noda's in his Banzuke, to see where discrepancies between them lie.

-

Thanks, Pete. I have yet to get this book. Do you happen to know if Kokubo provides any criteria/explanation for his ratings? Cheers, Steve

-

Hi Sebastien, I do believe such rankings exist in at least a couple of Japanese publications, but the only one I have seen recently and which I found most intriguing was a "Banzuke" ranking list Markus Sesko published in his blog post of October 2, 2016. I highly recommend locating and reading this post. Markus references this banzuke, noting that it is titled Tohken Tsuba Kagami and that it was compiled by Noda Takaaki, a sword-fittings expert, in the early 19th century. What I find especially interesting here is to see how various tsubako that have certain reputations now were viewed 200 years ago. Markus observes that this ranking list seems to focus only on tsuba artists working in iron, as it excludes kinko artists. I, too, would be interesting in knowing about any other specific publications which provide such ranking lists, especially for iron/steel tsuba. Cheers, Steve

-

Restoration Of Tosogu, Nihonto, Etc...

Steve Waszak replied to Steve Waszak's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Gents, Some excellent thoughts expressed here in your posts. They are much appreciated. Henry, thanks for clarifying what you'd meant by change. Yes, I see now what you mean. I do wonder now if part of my initial question wasn't really at heart concerned with the tension (and confusion?) between the terms "restoration" and "conservation." I got the ball rolling in an unhelpful direction by referring to the treatment of the Velazquez painting as a "restoration," while the term "conservation" was used in the article itself. I suppose I had been assuming that conserving something had mostly to do with preserving it in its current state (i.e. before any [further] damage could befall it), and that restoration meant more of an active intervention to "undo" the ravages of time (and prior actions), and so I saw the treatment of the Velazquez as an effort to "restore" the painting to something approximating its original appearance. I appreciate, too, Henry, what you have to say about conservators/restorers looking to preserved examples of similar pieces as guidelines for a treatment process. This would assume, though, that these preserved examples (in shrines, for instance) are themselves in "proper" condition (which kind of gets back to my initial query ). But yes, I can see where if such "model examples" do exist, that would provide an excellent blueprint for how to proceed and the goal to be sought. Jean, I appreciate your comment in the last sentence of your post concerning the restoration/conservation possibilities in the case of an iron tsuba that has been heavily corroded. While the condition of the piece might be improved, it would seem impossible, as you say, to bring the guard back to anything very close to its original state. One quick side comment here on the rarity of Kaneie tsuba: I think what Henry and I are referring to when we speak of this rarity are O-shodai Joshu Kaneie tsuba, of which I believe only five are thought to exist. Personally, I don't consider the Edo Period "Kaneie" works to be true Kaneie tsuba. Jason, your thoughts on eras and cultural differences are definitely thought-provoking, too. Thanks. But I wonder if there might be a difference in our discussion here between swords (and their purpose, including mysticism and functionality) and, say, an iron tsuba, when it comes to questions of conservation/restoration. Once again, thanks, guys, for your posts in this thread. Lots to think about... Cheers, Steve -

Restoration Of Tosogu, Nihonto, Etc...

Steve Waszak replied to Steve Waszak's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Henry, Thanks for the post. You express some interesting thoughts and sentiments here, which I shall ponder further. To respond briefly to a few of these, first, yes, I have asked too many questions. Apologies. But thank you for underscoring the distinction between conservation and restoration. I think this is a worthwhile difference to note, but ultimately, I'm not quite sure it speaks to the core question I'm asking, which has more to do with how we know what state an object "ought" to be in (and who has the "authority" to determine this). Actually, the penultimate paragraph from the article by Frank Matero you linked us to, Henry (thanks for that, too, by the way), more or less zeroes in on that question. I have reproduced this paragraph below: "Within the contemporary discipline of conservation, it is possible to find any number of incompatible, diametrically opposed viewpoints and work methods—from the idealist one that hopes for an impossible return of the object, structure, or site to an origin that can never be established with any certainty, to the pragmatic one that permissively treats as historical values all the alterations made over time. To this must be added the recognition of cultural and community ownership and the input of those other interested groups in the decision-making processes that remain the primary responsibility of the profession." (Matero) In this paragraph, Matero stresses two "incompatible, diametrically opposed viewpoints and work methods" in contemporary conservation dialectics. It is these viewpoints/work methods that particularly interest me. The initial link I put up---to the Velazquez restoration---clearly describes a restoration (rather than a conservation) effort (according to the definitions/descriptions you have in your post, Henry ), and would seem to lean, anyway, towards the first of the two possibilities Matero offers---the "'idealist' one that hopes for an 'impossible' return of the object...to an origin that can never be established with any certainty..." Of course, the restoration of the Velazquez painting is not really an effort to return it to its literally pristine original state, but the effort does seem to be much more in keeping with this sentiment than the other of Matero's possibilities, that of a "pragmatic [approach] that permissively treats as historical values all the alterations [e.g. layers of varnish] made over time." This latter approach/sentiment would seem to "appreciate" the condition of the Kaneie tsuba I posted images of. I guess I'm wondering how it is determined that a privileging of original-state idealism (in the case of the Velazquez restoration) is to be preferred over an "appreciation" of historically accrued alteration (i.e. several layers of varnish). Mind you, I'm not saying there's anything wrong with preferring the former (far from it, actually); I'm just very curious as to the thought process here and how relative values are prioritized. Henry, you'd also said that "for the past to be relevant it must be framed in the present and this continuity and relevance is established through change." I was a bit confused by your words here, though: by "change," did you mean that the object under conservation efforts would be physically changed/altered? Part of my confusion might be because framing something from the past in present contexts and perspectives is one thing (it does not require physical alteration of an object), but literally changing an object (physically manipulating it) is another, I think. But I could be misreading, so some clarification here would be appreciated. Many thanks again for your post, Henry. Cheers, Steve -

Restoration Of Tosogu, Nihonto, Etc...

Steve Waszak replied to Steve Waszak's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

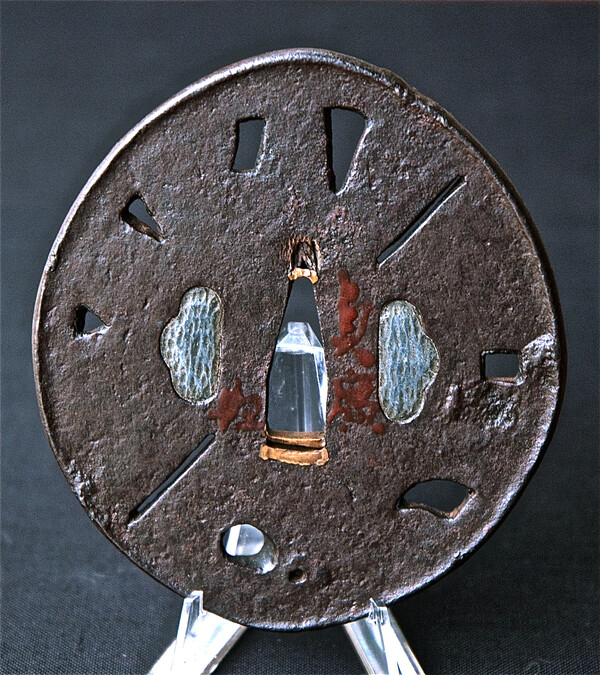

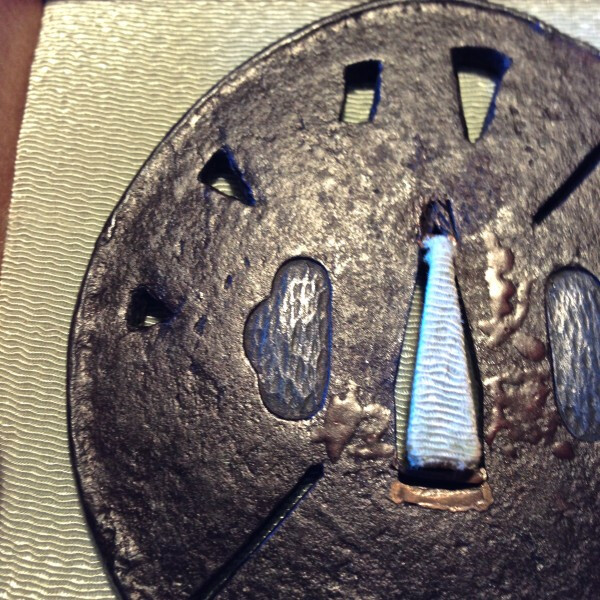

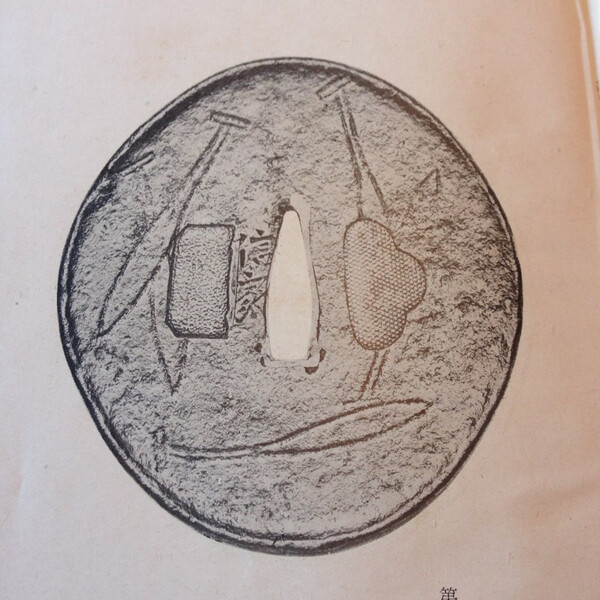

Many thanks to all for your well-considered replies here. I find this topic to be rather vexing, for it introduces such pointed philosophical questions: to conserve or restore? Or, is this a false dichotomy? Is restoration a form of conservation? What, exactly, are/should we be conserving? Artist intent? Can this really be known 400 years later? Or are/should we be conserving a particular state of signs of aging? What if these two contradict? Which are we prizing more highly, the vision of the artist or the state of the object (assuming for argument's sake that these do not align)? Such questions are made even more complicated when we consider others: if restoration is decided to be the better path, this path is fraught with various perils. What is the sensibility of the restorer? What should/"should" this sensibility align with? The intent of the artist? A specific idealized state of signs of aging (e.g. patina)? The desires of the current owner of the object that it look a certain way? A particular "consensus" of "expert" opinion on how such objects should look or the condition they should be preserved in? What are the skills of the restorer irrespective of his sensibilities? And do we, as temporary holders of these objects, have the right or license to act on or alter their state/condition? What if good-faith attempts to properly preserve or conserve them ends up causing (more) damage to them, such as can occur when, in efforts to preserve a patina, we allow corrosive rust to eat away at the surface of the piece? I apologize for dumping so many questions here at once. If I may try to simplify matters, I guess the basic tension I am asking about concerns artistic intent as a primary value, on the one hand, and signs of graceful aging as a primary value, on the other. I have seen iron tsuba, for instance, which present with various substances on the plate. These can range from lacquer and wax to oil, paint, and shoe polish, in addition of course to rust and dirt. Of course, we might agree that some of this material should be removed. But if none of this material was intended to be there by the artist, should(n't) all of it be removed? What if attempts to do so damage whatever good patina is under all that gunk? Some might say that the threat to the patina makes such attempts too risky, and that they ought not be undertaken. But then, if we can't even see that patina (never mind the fine details rendered by the artist originally), what good is that patina (in terms of aesthetic appreciation)? *Note: I will leave the question of whether a "perfect" 400-year-old patina, which is not what the artist "intended" when the object left his workshop, doesn't then actually occlude our apprehension of artist intent... It is easy enough, I suppose, to address questions of conservation (vs. restoration) if that tsuba is in an ideal state (i.e. all intended details of the artist are preserved [except, perhaps, the specific original color, which we can't pretend to know some several centuries later], and there is a deep patina across the entire surface, with no rust evident). When this "best of both worlds" is the state of things, most are probably pretty happy with matters. But what if we are confronted with an important steel tsuba that does not present in such a state? Below is a tsuba, made by Kaneie. It is considered by some to be the most important tsuba in existence, and by many others to be among the most important. How would you describe/assess its condition in these photos? Ideal? Acceptable? Unacceptable? It seems to me that, given the lofty reputation of this piece, and given that it exists in a situation (part of hugely important collection in Japan) with plenty of access to restoration resources, its state of preservation ought to approach the ideal. Would we agree that it has been preserved such? *I have included two versions of the photo, one with enhanced color to show better areas of rust on the plate. Thanks for indulging my OCD query... Steve -

Gents, I wanted to present a link to a short piece on the restoration of Velazquez's Portrait of a Young Girl (Ca. 1649) because I think it raises interesting questions pertinent to our interests in nihonto, tosogu, katchu, etc... Here is the link: http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2016/velazquez-portraits/portrait-of-a-young-girl I am certainly not posting here in order to flame or be a troll on this subject. Rather, the subject of restoration invites intriguing philosophical, aesthetic, and historical questions and pondering. Too often, it seems to me, viewpoints on restoration are perhaps too rigid or close-minded, and/or are arrived at by uncritically examining the position of various authorities (or "authorities") on the matter, without investigating the assumptions, values, or beliefs held by those individuals. So, as concerns this Valazquez painting and its restoration, I would like to invite a discussion on where, why, and to what degree the approach taken in the restoration of this painting might differ or be similar to that taken in the restoration of, say, an important early steel tsuba. For instance, are there any here who might object to any (or all of) of the restoration undertaken with this painting? Are there any who would hold the position that the accrual of the material (dis)coloring the canvas should be seen as a positive thing, worthy of appreciation? Or, would all agree that the restoration was necessary and/or a positive action? Again, I am not seeking to bait anyone or lay a trap . I am genuinely interested in the philosophies involved in questions of restoration and its methods, degrees, and which objects could/should be considered for restoration, and why. In returning to that important early steel tsuba (let's make it a Kaneie, for ease of reference), then, if that tsuba presented in a condition effectively analogous to the Velazquez painting prior to any restoration (as seen in the link), would we "leave well enough alone," or perhaps even appreciate the various layers of material as signs of the "beauty of aging"? Would we remove some of these layers but not all? If so, how would we decide how far to go with this, and based on what values/beliefs? Or would we look to achieve the effective equivalent of the end result of restoration process with the Velazquez, and remove as much of that material covering the original canvas as possible? If so, why? If not, why not. I would appreciate it if we could keep this discussion as civil and academic as possible... And I look forward to others' thoughts on this. Cheers, Steve

-

I have a tsuba that has been attributed, both by the NTHK and via shumei (don't know who did the shumei), to Sadahiro (Owari). I had the tsuba for more than two years before one day, turning the guard in the light, I saw what is an "abraded" or almost-erased Nobuiye mei. The signature is of the Futoji-mei variety, and what remains of it (the "Nobu" ji is still visible; the "ie" ji is essentially scrubbed away) confirms the particular style of rendering that ji that the nidai Nobuiye employed (some scholars have this artist as the shodai, but most, I believe, recognize him as the nidai). I have been perplexed as to why there would have been an attempt to remove the mei, unless some previous owner considered it gimei. A shame, since the piece itself is clearly---according to many production details---genuine nidai work. Here are photos of the tsuba, including close-up images of the seppa-dai. I have also included photos of two similar guards made by nidai Nobuiye (first two images). The "journeys" these works take over time is fascinating... Cheers, Steve

-

Always enjoy and appreciate your posts, Darcy. Thanks.

-

Insurance And On Site Security

Steve Waszak replied to GARY WORTHAM's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

My home defense consists mostly of these... Few thieves are desperate enough to try getting past two or three well-trained mastiffs... They are amazing, loyal, protective dogs. They're also on patrol 24/7, hear and smell anything amiss, weigh some 70-80kg each, and will guard the home with their lives. -

Thanks for the good tip, Peter.