-

Posts

978 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

4

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Steve Waszak

-

Curran, Oh yes, THAT Yamakichibei is burned into my memory! A brilliant tsuba. Same guy got that as won this Hikozo auction, yes. He's had many other successes, too. That Yamakichibei went for over a million yen, by the way... Stephen, yes, it would be good to know who this guy is, though as you say, that won't help us outbid him at auction!

-

I expected, as I suspect Pete did, too, that this guy would walk away with this tsuba in the end. Seems like these days, for pieces of superior quality/importance like this one, he nearly always does. But I am surprised by the low winning bid: only about half of what I'd have thought. Pete's supposition that other bidders give up when they see that this guy has entered the fray is probably accurate, and could explain why this didn't go higher. Quite a collection he is putting together.

-

Edit accomplished.

-

Ford, Those questions you ask at the end of your recent posts are all good ones, and thought-provoking. Each deserves its own thread, though. Just a quick comment about evidence. You ask whether there is any "actual historical evidence" supporting some of the "accepted wisdom" out there. Your query raises interesting further questions regarding what counts as evidence. I think from your post that you are referring to concrete, incontrovertible evidence. I wonder how often we really do have this kind/degree of evidence supporting what we know/"know" about nihonto and tosogu. You zero in on a handful of examples, which are all good, but couldn't this list be expanded almost infinitely? Epistemological issues and questions are teeming in our studies in nihonto and tosogu, it seems to me. This is due to many factors, but at least two stand out. One, of course, is simple historical distance: when we are talking about artists, smiths, and objects dating back multiple centuries, the potential for murkiness in knowledge acquisition is high. Added to this is the obfuscation created via invented genealogies, iemoto-ism, perpetuation of myth and (other) romantic constructs, reliance on tradition, etc..., and what we're left with is or should be a lack of confidence in what we (think we) know about swords, tosogu, and smiths/artists. Believe me, I'm a huge fan of actual historical, concrete evidence when we have it. But what to do, then, when we don't? I think what many of us tend to rely on---if traditional sources of knowledge are looked upon with healthy skepticism---is circumstantial evidence combined with sharp inductive reasoning. We may be (usually are) forced here to rely on likelihoods and nothing more, since anything more would have to come out of our having "actual historical evidence." Some likelihoods are greater than others, of course, depending again on the strength of specific circumstantial evidence as well as on one's powers of inductive reasoning. In the end, we are left to make the best arguments we can for the conclusions we draw (even if with some tentativeness or qualification), as those highly desirable incontrovertible historical facts we seek are so often absent, and will likely remain so.

-

I wouldn't be surprised in the slightest to see this zoom past the million-yen mark... And that wouldn't be an outrageous price for it, not even close.

-

Really fascinating, Peter. Thanks for posting this. He was definitely a complicated man. I did a lot of writing on Mishima in grad school: there is much more to him than may at first meet the eye.

-

This Is Well Worth Reading:

Steve Waszak replied to Pete Klein's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

I do wonder---speaking now of early iron fittings---how many of such works could have survived the centuries enduring Japan's climate without having been "attended to" across their long lives. Is it really possible for an early-Edo (or earlier) iron tsuba to have made it across 400 years never having been cleaned, oiled, waxed, re-patinated, etc...? I suppose it's possible, but it must be a relatively rare occurrence, no? I can't help but wonder what the de-rigueur care of iron fittings was in pre-Modern Japan. How was a 16th-century ko-Katchushi sword guard cared for/attended to 100 years after its production? 200 years? 300 years? I don't know that we can really ever know such things, especially as philosophies, practices and customs may have changed over the course of time and/or been different from region to region. Here's a link to an interesting discussion on the matter of restoration and conservation of such objects: http://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/21171-restoration-of-tosogu-nihonto-etc/?hl=%2Brestoration+%2Btosogu. In the end, whatever our particular subjective philosophy may be concerning suitable approaches to conservation and/or restoration of fittings, cultural, political and economic factors will always complicate matters to the point of threatening any clarity we might have on the issue in an ideal world. -

This is a yon-ji mei, correct? I think I see the first one as "Yama."

-

Hi Evan, Lids on mizusashi are a rather interesting sub-topic. As is probably not surprising given the many intricate aesthetic considerations attaching to anything Tea, the type of lid on a water jar carries different connotations of formality and status. While lacquered lids are considered more formal, ceramic lids hold a higher status, despite their appearing less "polished." I believe that many lacquered lids are original to the piece. High-fired ceramic stoneware is not especially likely to break, and even if a lid were to be damaged, the art of kintsugi would, perhaps, allow for it to continue to be used. The contrast between the earthy strength of Bizen, Shigaraki, and Iga vessels, on the one hand, and the smooth black, lustrous polish of the lid used on a mizusashi, on the other hand, I'm sure expressed an aesthetic that had high value in Tea Culture sensibilities. Same would go for the ivory lids on tea caddies, though here, the contrast would likely be much more subtle, since caddies themselves were usually less "crudely wrought" than works coming from Iga, Bizen, or Shigaraki kilns. Cheers, Steve

-

A very nice modern piece here, Evan. Thanks for posting this (and the review of Bizen firing practices... ). Here is a ko-Bizen "pail-type" Mizusashi I managed to acquire earlier this year. The colors and textures achieved in the firing process on this piece are really excellent. Late Momoyama to earliest Edo. Cheers, Steve

-

Hi John, Thanks for your post here. All interesting stuff. My particular interest in this topic concerns Naomasa's dates, though, more than the typing or categorizing of Onin guards. I remain dubious about this tsuba maker's working dates being any earlier than late-Momoyama. The tsuba you reference dated to 1533 is certainly eyebrow-raising: I have to think there is an error here somewhere (as you have suggested), or simply represents an attempt to deceive. The article on Onin tsuba you provide the link to notes that Naomasa's "name is found, sometimes genuine, sometimes forged..." Given the esteem Naomasa's work was apparently held in, the notion that his signature (including dates?) could have been added later to mumei pieces isn't much of a stretch. So I don't find the tsuba dated to 1575 necessarily very compelling as hard and fast evidence, either. Another consideration here concerns the cultural and aesthetic climate of the time. Compared to the relatively austere sensibilities of Muromachi years, the Momoyama Period was far more flamboyant and alive with experiment and exuberance of expression. Yoshiro tsuba fit this context much better than they would a 1550s or 1560s dating, in my view. Then there is Ford's very intriguing work in researching brass availability and use in 16th-17th century Japan (many thanks for this post, Ford! ). Putting all of this together, it is hard for me to see Naomasa's working period beginning any earlier than the 1580s at the very earliest, with the 1590s more likely, assuming the Hideyoshi quote is legitimate. If the Hideyoshi quote is apocryphal, then I could see Naomasa's working period being even later by a decade or two. Cheers, Steve

-

Hi John, Thanks for the detailed response. Very interesting. I would certainly agree that the dated piece would very likely carry a signature, too, if for no other reason that it would be hard to know for sure that the tsuba was made by him if it weren't signed. If it were not signed, however, the inscribed date may be spurious. There were only a very few tsubako who regularly inscribed their names as early as the 1570s, so your information here is quite intriguing. In your research, did you find any mention of Naomasa's being affiliated with or serving under any particular lord? I would also be curious to know Ford's thoughts on this artist and on the matter of his working period, given Ford's research into earliest brass inlay in tsuba. Thanks again, John. Cheers, Steve

-

Hi John, Your original post mentions that Koike Yoshiro Naomasa lived in the third quarter of the 16th century. From what I've read, he was more of a late-16th century/early 17th-century man. Could you offer your source for this early dating? Thanks. Steve

-

Very sad news. A good man indeed. Rest in peace, Harry...

-

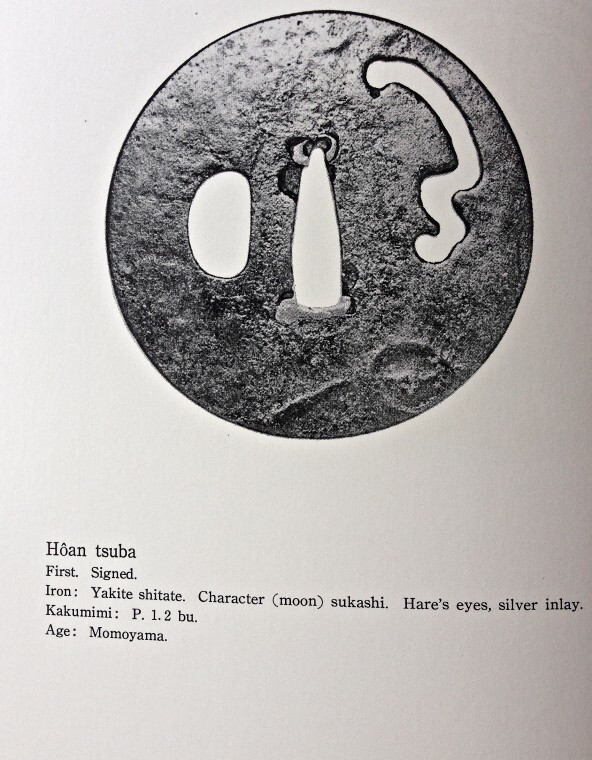

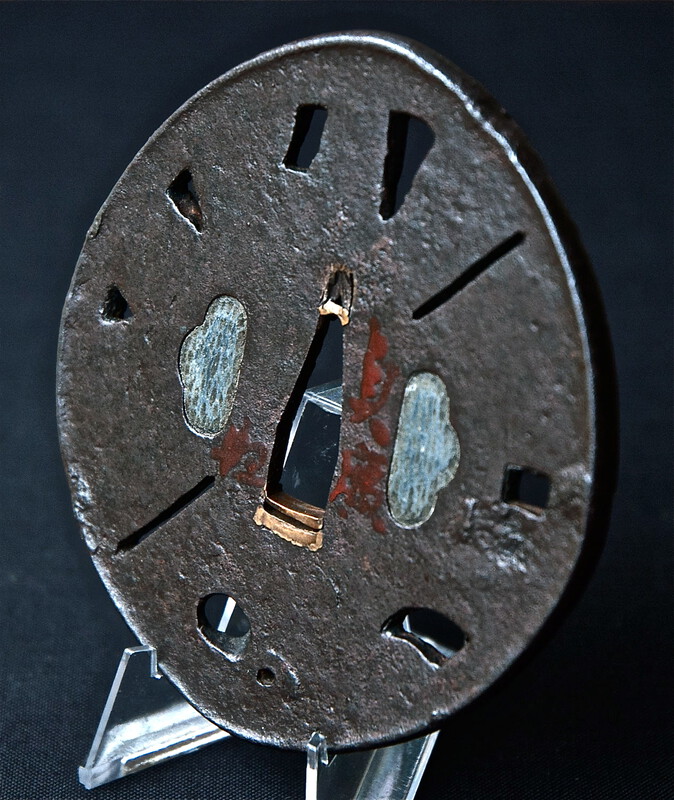

I'm a fan of this theme as well. My favorite rabbit-and-moon tsuba is below, an iron tsuba made by (shodai) Hoan. The moon is represented by what I believe is a sosho script form of the kanji for "moon." The rabbit's head is presented in a rather oblique way, in a subtle relief carving combined with yakite-kusarashi, with part of a long ear continuing onto the other side of the tsuba. A simple, but powerful design, IMHO. The image is taken from Dr. Torigoye's Tsuba Kanshoki. Cheers, Steve

-

The One You Regret The Most

Steve Waszak replied to lonely panet's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

My biggest regret came to have a happy ending. Some years ago, during a particular period of upheaval for me, I recklessly let the tsuba below get away. I regretted it almost from the moment I did so, but I had sold it to a collector who promised me right of first refusal in the event he would be looking to sell it. A couple of years later, this came to pass, and I was fortunate enough to get it back (thanks, M! ). I've had a few other smaller regrets, but none on the level of this one. So I am grateful that the gods smiled on me here... -

Wow. That's a shame. Certainly looks as though some substance has been applied to the whole piece and then the tsuba was buffed with an electric shoe polisher. Can you even see the actual steel now? As you say, Curran, it's definitely worse off now. Steve

-

Thanks for posting this, John. Curiously, I was looking at this very tsuba just last night in regard to early mei... However, these dates for him are, I think, a little ambitious on the early end. To me, his work expresses a sensibility that is more Azuchi-Momoyama to earliest Edo than Muromachi.

-

Rich, Yeah, I've always liked this piece... You may want to do a bit of comparison study of the mei on this tsuba with those appearing on some of the kabuto with Nobuiye's name. Going by memory (always reliable... ), the rendering of the mei here with those I've seen photos of on the helmets seems to have some similarity. There is, of course, a rather large amount of debate/controversy surrounding "Myochin Nobuiye," though, with some arguing that he is a mythological figure, and that all Nobuiye mei on extant kabuto are fakes, so it may be hard/impossible to draw any solid conclusions about the mei on this tsuba and any of those on the kabuto.

-

Hi Grev, There are actually quite a few tsubako who were chiseling their mei prior to Edo times. Among them are the Nobuiye men, Kaneie, the Yamakichibei tsubako, Hoan, Sadahiro, Umetada Mitsutada, and Umetada Myoju. There are also rare examples of other signed works believed to be pre-Edo, such as pieces by Myochin Takayoshi and Nobusada. The practice of signing tsuba appears to become established during the Momoyama Period, though it was still relatively infrequent considering all the tsuba makers working then.

-

Thanks, Rich. I have to say, I don't have a great deal of faith in the genealogies for pre-Edo groups. We've seen the question marks surrounding the genealogy of the Myochin family/group of armorers (at least pre-Momoyama), and the apparent murkiness of the origins of such tsubako schools as the Umetada and Akasaka makes me somewhat dubious of their published genealogies. You note that the Umetada made this design a lot: were they usually of this sort of dimension, though? This piece is, what, 86mm or so?

-

Rich, Great tsuba. The photo of the "blerb" you include here raises interesting questions concerning the maker of this piece. You note that the physical state of the guard suggests it was made in the Momoyama Period. I don't disagree: the various signs of age concerning the tsuba's condition, plus the size and exuberance of the motif point more toward this period than to Edo, I believe. But what's interesting here is that Umetada Myoju (the maker of the signed guard above) is a Momoyama man. So if this tsuba was not made by him, but is of his time, who might the specific tsubako have been who did make it?

-

Hi Barry, Your friend is spot on...

-

Curran is correct: Nobuiye.