-

Posts

978 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

4

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Steve Waszak

-

Which Of Your Tsubas Best Embodies The Wabi-Sabi Aesthetic?

Steve Waszak replied to lotus's topic in Tosogu

Curran, Great tsuba. To me, that is a good example of several aesthetic values/principles joining together. There are wabi (the weather-beaten look of the sahari) and sabi (mushrooms, which grow so incredibly quickly, allude to the transience of things). But there are also haki (the way the mushroom is rendered is very powerful/bold) and shibusa (sahari is not glitzy and gaudy; it is a much more subtle contrast with the iron). Love this piece. Pete, And this kozuka: mono-no-aware, yes, I absolutely agree. But it, too, also expresses sabi and shibusa, IMO. The placing of the moon on the reverse, rather than on the front along with the birds, achieves a beautifully shibui effect. And the birds together with that silvery moon...practically aches with sabi. I imagine an allusion here to deep autumn. Wonderful kozuka. -

Which Of Your Tsubas Best Embodies The Wabi-Sabi Aesthetic?

Steve Waszak replied to lotus's topic in Tosogu

These terms ---wabi and sabi --- are just two of dozens employed in expressing aesthetic sensibilities in Japanese culture. It is useful to familiarize oneself with at least some of the others to get a more balanced view of how the Japanese see and describe different facets of beauty. Donald Richie's book, A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics, is an excellent introduction to this arcane world. Florian stated that, "omeone could read a lot about wabi-sabi but has not the slightest idea what the term means. There must be an individual understanding. It’s rather an expierience that can’t be explained." While I agree in part with what Florian says here, I think it is more accurate to say that we can fairly easily get a general idea of what wabi and sabi mean, in the same way we can have a pretty good understanding of what the abstract term "beauty" means. What I think Florian is getting at is the specific application of wabi or sabi to a particular object, environment, action, etc... That is, in the same way we all understand what beauty is/means abstractly, we won't agree on what counts/qualifies as beautiful. And just as it can be difficult to explain why this particular landscape is more beautiful in our eyes than another, it can be hard to articulate why this tsuba expresses wabi more powerfully than that one. So when Florian says that "[t]here must be an individual understanding," this seems right to me, just as we all have our individual understandings of what counts as beautiful. This doesn't mean we can't argue for what counts, though! Incidentally, the joining of the two terms, wabi and sabi, is way over-used, especially outside of Japan. These are two separate aesthetic principles. They can work together, but so can sabi and mono-no-aware, and so can wabi and haki, or shibusa and sabi, etc... So we shouldn't automatically be linking these two as though they must go together. Here is a tsuba that I would see as expressing both sabi (a sense of loneliness and the melancholy that accompanies it) and wabi (an abiding sense of exquisite "poverty" borne of the impact of time and conditions, creating a state of deep wear, and thus, "imperfection"). As I see it, the motif of the birds, the reeds, and what looks to be a hanging fishing net expresses sabi. It likely alludes to a specific season (as Japanese artworks so often do), which connotes (for the Japanese) certain emotions. In this case, that emotion is melancholy, perhaps in recognition of the inevitable transience of things (the constant passing of seasons will amplify this recognition). The working of the plate --- the tsuchime and yakite kusarashi utilized by the tsubako (Hoan) --- carries a wabi sensibility. The one value (wabi) interacts with the other (sabi) to create a subtly powerful work. All IMHO of course. Cheers, Steve- 152 replies

-

- 17

-

-

In The Defense Of Shinsa & Papers

Steve Waszak replied to Jussi Ekholm's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

I think everyone makes some very good points and arguments here. Certainly, shinsa teams have years of accumulated experience and knowledge, especially in the aggregate, that few, if any, outside of Japan can match. Speaking as someone who has never submitted an item for shinsa, my words here do not come from having been disappointed in a shinsa result. In fact, I have one piece with a very favorable big-name attribution by the NBTHK (the paper accompanied the mumei tsuba when I acquired it), but I remain a bit dubious about the tsuba due to certain particulars in its rendering. But I digress... My main issue with shinsa/papers has very rarely been about results, per se, but in the lack of explanation for the result. My feeling is that if we are spending meaningful amounts of money to send items in for shinsa, we should receive not only a result/attribution, but also some education concerning why the result is what it is. This would go a long way toward not only justifying the outcome, but also allowing those submitting pieces to learn. There would be a lot less disgruntlement with disappointing results if a reasonably detailed explanation accompanied that result. I recognize, of course, that shinsa teams wouldn't have time to provide in-depth explanations for every piece submitted, but I do wonder if busy shinsa teams offered a detailed explanation for an additional fee, how many of those submitting items would or wouldn't choose to do so. I know that, personally, I would be far more likely to submit items, even if it cost more, were such an explanation to accompany the result. My other main issue with shinsa has little if anything to do with shinsa at all. Rather, it is the idea that a shinsa result is a factual determination, and not what it actually is: an educated perspective/opinion. I have seen many say things like, "Why don't you just submit the item to shinsa; then you'll know what it is." Such a statement is made false by the last part: "...then you'll know." To say that this information will be known is to say that it is objectively factual. Unless we were there those 400 years ago to see the item in question being made, we can't know. What we can have, though, is an experienced, highly-knowledgeable assessment (made much more valuable by an accompanying explanation for that assessment), and that is the language we should be recognizing and using. Shinsa team members can and do disagree on items from time to time. If one extremely experienced, knowledgeable shinsa team member disagrees with another, both of whose learning far exceeds that of most of us, which are we to trust? How can we know about an item when shinsa team members themselves don't always agree? And of course, when a shinsa result is provided, the paper doesn't note any disagreement, so we can't know in which cases unanimity was reached among the team members and when it wasn't. This only further destabilizes the notion that "...then you'll know" when submitting a piece to shinsa. The bottom line is that shinsa is another learning tool for all of us in this pursuit. It can be valuable (and could be even more so---see my first point above) when its limits are properly recognized. -

Offered here is a rather large iron tsuba (80 x 77mm, 2-2.5mm at the nakago-ana) that may be an example of Tembo work. The sukashi (I believe of a crescent moon and two stars...or maybe Mars and Venus) are executed in an angled manner leaving long "entry points" of the chisel on each side of the plate. I am not familiar with Tembo work that employs sukashi in this way, so this guard may be an example of another tradition's work. The kokuin (stamps) that appear on the plate are of course very much in the Tembo tradition, and the heavy working (hammering) of the surface, too, is a fairly classic sign of Tembo aesthetic sensibilities. This tsuba boasts beautiful iron and possesses a lot of rustic charm, but also projects a degree of strength and solidity. I would conservatively date the tsuba to 19th-century, but it could in fact be much older. SOLD . Please let me know if you have questions... Cheers, Steve

-

Hi Jean, Yes... What I meant there was "rejected because it wasn't seen as being genuine."

-

Darcy recently added another excellent entry on his blog, this one titled "Pragmatism." I highly encourage giving it a read. https://yuhindo.com/ha/ Briefly, Darcy notes the extreme unlikelihood (read impossibility) that some lucky collector will be able to sniff out an ultra-rare and important treasure when that treasure is in Japan, and is being offered by a Japanese seller on a Japanese auction site for next to nothing. Darcy's very logical argument is that this seller---if he thought he even might have the real thing---would take advantage of his proximity to the wealth of knowledgeable dealers, collectors, and experts there in Japan to verify that the piece in question was genuine. Whereupon, if discovering that the item was not, he might look to dump it onto an auction site at some low-ball price, wanting to be rid of the fake. In other words, if we happen upon an item in a Japanese auction that is purported to have been made by an important smith and is being offered for relatively little money, we should recognize how improbable it is that this would actually be an authentic work by that smith, and not waste our time and funds on such a piece. I don't think there is much room for disagreement with Darcy's assessment here. However, "never say never" is a sentiment that can keep hope alive, even in the face of the pragmatism Darcy is encouraging all of us to practice. For there are exceptions to (nearly?) every rule. Once in a full lunar eclipse blue moon, a treasure can fall through the cracks. This example, while not sword-related, still proves essentially analogous, I think: https://paleofuture.gizmodo.com/everyone-thought-this-coin-from-the-california-gold-rus-1825498372 Of course, in this case, the item did turn out to be authenticated by a higher-level expert after having been rejected as fake by a number of lower-level authorities, but imagine if the coin had been put into auction after several of these (still knowledgeable and experienced) lesser experts had declared it not to be genuine. My point here is that, while Darcy's advice is excellent and should absolutely be the rule of thumb in navigating the waters of Japanese auctions, we need to do our own studying and research such that if and when an important "blue moon"-type item does appear, even though we recognize that the item in question most likely will have been circulated (and rejected as genuine) among experts in Japan, our own studies may allow us to remain open to the possibility that a gem has slipped through those admittedly tight cracks. We are talking about once-in-a-lifetime sorts of situations here, though, so Darcy's caveat still holds with resonance: Don't plan on winning the lottery, even if there are such things as lottery winners. Lottery winners are not quite unicorns, but for all pragmatic purposes, they may as well be. Hope may spring eternal, but focused, smart, and diligent study is really what can give substance to that hope... Cheers, Steve

-

Sergei, Kudos to you for your efforts in compiling this. You are to be commended! Unfortunately, however, there are many errors (not yours) in the understanding of Yamakichibei revealed through this compilation, and many errors in attribution across the sources you present here. Of course, some of these attributions are correct, but others are exceedingly problematic. Going through all of the content and images your compilation provides would be quite time-consuming and complicated, I'm afraid. I am thinking that a formal article/monograph on Yamakichibei sword guards is truly necessary at this point, and have begun considering how I might put this together. Barry Hennick has invited me to submit just such an in-depth article for the JSSUS, and so that may be the venue for me. Again, I want to applaud you, Sergei, for your focused effort and enthusiasm here. I'm sure I am not alone in saying it is much appreciated! Cheers, Steve

-

Yes, there are four Yamasaka Kichibei pieces, and twelve "Meijin Shodai" examples, plus a reproduction of an oshigata which may depict a Yamasaka or a Meijin Shodai" tsuba; it's too difficult to tell from the image whose work it is, though it looks to me more like Yamasaka's than Meijin Shodai's. *Note: of these twelve "Meijin Shodai" examples, at least three, and possibly a fourth, are erroneously attributed to him. So only eight or nine of these are actually his work. There are also several Sakura Yamakichibei sword guards, but I do not consider him part of the actual Yamakichibei atelier, since he worked at least 30-40 years (perhaps more) after Nidai Yamakichibei was active.

-

Offered here is a very fine tsuba made by one of the "Three Owari Masters of Genroku," Toda Hikozaemon (Fukui Jizaemon and "Sakura" Yamakichibei were the other two). Toda Hikozaemon tsuba are known for a number of features, including exceptionally fine amida-yasuri, a finely-rendered goishi-gata, a delicately-worked uchikaeshi mimi, and ko-sukashi motifs. This tsuba exhibits all of these, with the amida-yasuri being especially brilliantly done in its extreme subtlety. The color of this tsuba, too, is extraordinary, being close to that of the wet sand on the beaches of southern California (a dark taupe). The Owari-ume plug is a perfect complement to the color of the plate, while the sukashi motif of crossed hats fairly dances across the field on the other side of the nakago-ana. The tsuba also boast the beautifully soft sheen of an old patina. The seppazuri indicates significant time spent mounted on a koshirae. The tsuba is signed with the unmistakably idiosyncratic calligraphy of Toda Hikozaemon, a lightly-incised loose "scrawling" that is much appreciated by many for its verve and unique character. Toda Hikozaemon worked in Owari Province in the latter 1600s. His work is generally very well regarded, and certainly in his own time, he was a major tsubako, being included, as mentioned above, as one of the "Three Owari Masters of Genroku." The Genroku Period lasted some 16 years, from 1688-1704, and is know as a time of artistic renaissance of sorts. Toda would certainly have been a significance artistic voice of the age. For more on Toda Hikozaemon, please see Okamoto's Owari to Mikawa No Tanko and Art and the Sword, Volume 3. SOLD Size is 75.2 mm x 5.5 mm at the nakako-ana. 134 grams. *Note: at approximately 3:00, there is a tiny mark on the mimi that appears to have been made by the blow of a sword. No idea, though, what this actually is. The depth of this cut is minimal, at less than 1mm. Cheers, Steve

- 1 reply

-

- 6

-

-

All of those black and white images are of nidai Yamakichibei tsuba, Sergei.

-

Tim, Some good ceramics examples there. Thanks for posting these. You note in your last sentence that "ecause Buddhism was of vital interest to both the Tea Master and the Warrior, it is not surprising that the unique visual language developed for cha-no-yu crossed over into tsuba." Yes, a very important point here. However, I think it must be emphasized that only relatively few tsuba (types) "spoke the language of Tea" as the works of Yamakichibei, Hoan, Nobuiye, and some of the Higo masters did. The high-level aesthetic principles informing wabi-cha and its utensils, architecture, interior and garden designs, were manifest only among a fairly small group of (especially Owari) tsubako in the late-16th and early-17th centuries. Besides ku and haki, which have been mentioned, and the wabi of wabi-cha, principles such as shibusa, sabi, mono no aware, and yuugen (among others) were ascendant and lively in many of the arts of the Momoyama age, including poetry, Noh drama, and of course, cha no yu. These were the arts of the Buke, and with Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi acting as driving forces marrying warrior and Tea culture in the 1570s, 80s, and 90s, the koshirae of high-ranking bushi would have been a natural residence for accoutrements that embodied and reflected such sensibilities. This would include the tsuba. Especially, the tsuba. It should be understood, then, that part of the greatness and importance of such smiths as Yamakichibei, Hoan, Nobuiye, and others who produced high-level "Tea tsuba" is in the very fact that their works were associated so tightly with Tea. Tea mattered to the highest-ranking members of the Buke in the Momoyama years, and it mattered a lot. It is, in fact, difficult to overstate the degree with which it did. When we combine the sheer mastery in iron their works exhibit, with the lofty aesthetic principles they embody and express, with then their historical and cultural importance, we have what I would argue represents the apex of tsuba art in Japanese history.

-

I think I can answer for Evan, Sergei. The color photos are of a nidai Yamakichibei offered in an auction last year. I don't know the exact dimensions on this guard (I don't think Evan does either, since I sent him the photos originally... ). This tsuba has Tokubetsu Hozon papers and is, in my view, a masterwork. The color of this piece, in particular, is fantastic, being of that "yohkan" hue that is so highly prized (the oblique images, as usual, show the color of the guard best). The black and white photos are all taken from Owari to Mikawa No Tanko. Cheers, Steve

-

-

Thanks, Tim. Yes, all good titles there. I have all but the Rikyu book. Another publication I recommend in order to get a good introduction into Japanese aesthetic principles (some of which so prominently feature in Yamakichibei tsuba) is Donald Richie's A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics.

-

Important to remember that in many cases, older literature (or brand new, for that matter) will contain and repeat errors, faulty and/or incomplete information, and questionable assumptions, premises, beliefs, reasoning, and conclusions. In order properly to pursue an analysis and assessment of a subject like this, it is crucial both to examine many examples of the tsuba in hand, as well as to educate oneself on larger historical and cultural contexts informing the creating of these pieces. Sharp skepticism is critical in this endeavor. Below are a few more photos of Yamakichibei guards. These include both "Meijin Shodai" (the last two examples) and Nidai pieces. Cheers, Steve

-

Sergei, The literature on Yamakichibei is scant, but one source you need to have is Okamoto's Owari To Mikawa no Tanko. I know Grey has had this title available in the past. There is an excellent translation, too. This book covers the tsuba smiths from Owari and Mikawa provinces (though curiously, the two early Nobuiye are omitted; perhaps Okamoto completed the book---an early 80s publication---before it was generally agreed that the two Nobuiye were Owari men). The section on Yamakichibei is the most in-depth and detailed in print I have yet seen. There are a few points Okamoto makes in his write-up that I don't quite agree with, or don't think are fully clear, but in the main, this is excellent material. As to the tsuba I posted the photo of, the mei reads "Yamakichibei," but it is a Yamasaka guard. How do I know? Lots of study and comparison of Saka tsuba with those of the Meijin Shodai. The literature states that Yamasaka Kichibei occassionally signed "Yamasaka Kichibei," but also signed just "Yamakichibei" at times. Yamasaka Kichibei is referred to as O-Shodai, while the "other shodai" is known as "Meijin Shodai." See studies of Kaneie for a similar situation as concerns shodai tsuba. In this particular piece, the workmanship and key details in the mei allow me to know it to be Saka work. You are correct, Sergei, in saying that there aren't a lot of reference photos of Yamasaka mei to be found. There are four Yamasaka tsuba illustrated in the Okamoto book. There are a couple of others in Nakamura's Tsuba Shusei, and the 2009 Dai Token Ichi catalogue not only has a good photo of a Yamasaka guard (complete with clearly legible mei), but also includes a photo of the Juyo Nidai Yamakichibei Otafuku-gata "blossom" tsuba that Sasano erroneously attributes to (Meijin) Shodai work in his "gold book." In the 2014 NBTHK Iron Tsuba Exhibition catalogue, there is a magnificent tsuba with a Yamakichibei mei that is a Yamasaka piece. This guard has many of the same features as the one I posted the photo of. Below is a photo of a Meijin Shodai sword guard. Cheers, Steve

-

Sergei, These tsuba you have presented here really have nothing to do with the actual Yamakichibei works of the Momoyama and earliest Edo Periods. They are "homage" pieces, if you will, but are only a hollow facsimile of the real thing. The inscription is "Yamakichi," as opposed to "Yamakichibei," and they always appear with those odd little holes (between 4 and 6) and carved lines in the vicinity of the hitsu-ana. Many of these were made in the 19th century, all with little variation, some 250 years after the actual Yamakichibei men were working. As for opinions on Yamakichibei tsuba overall, well, there is probably a range of viewpoints. Many here know mine, as I consider true, early Yamakichibei tsuba to be among the very best iron sword guards ever made. At their best, they are second to none, including Nobuiye and Kaneie. Their mastery of certain features/processes such as tsuchime, yakite, and tekkotsu, especially in combination, reached heights never to be surpassed, and rarely equaled, resulting in tsuba with great haki, or power. If one's taste is for sword guards with this sort of expressiveness, Yamakichibei works are at the top of the mountain. Of course, for many, such aesthetics hold less appeal. Yamakichibei tsuba are deeply connected with the aesthetics and culture of Buke Tea that was dominant in the Momoyama Period. The aesthetic principles informing cha no yu then---its ceramics and other articles, as well as the architecture and interior design---were of major importance to the leading figures (and thus their vassals) of the time. My belief is that one cannot properly appreciate or understand Yamakichibei guards unless one also studies the culture of Tea in the late-16th and early-17th centuries. If one cannot grasp what makes an Iga hanaire or Bizen mizushashi of that time a masterwork in ceramics, one may not be able to fully "get" Yamakichibei. There is much, MUCH more to be said about Yamakichibei, than can be adequately presented here. Perhaps a formal article is in order... Below is an early Yamakichibei tsuba (Yamasaka Kichibei). Cheers, Steve

-

Great tsuba, Tim. That second Hoan (the oval one) is wonderful, but the kikugata piece is spectacular. Best piece in this whole thread, in my opinion.

-

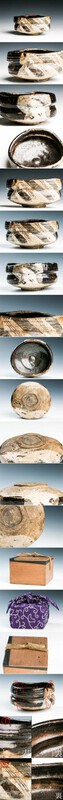

Seto Yaki Cha-Ire Tea Container In A Shifuku Bag

Steve Waszak replied to Robin's topic in Other Japanese Arts

Robin, Agreed: the lacquer repair is inspired. But I might suggest that the aesthetic principle here is more shibusa than wabi or sabi... -

Seto Yaki Cha-Ire Tea Container In A Shifuku Bag

Steve Waszak replied to Robin's topic in Other Japanese Arts

That is a beautiful cha-ire, Bernard. Really, really good. Cheers, Steve -

Some Japanese ceramics authorities argue that Shino is really properly understood to be "white Oribe" ware. When the origins of Oribe wares and Shino are considered, together with the clay types and the sensibilities reflected in certain aesthetic features, this view does make some sense... Cheers, Steve

-

Here is a period (Momoyama) kuro-Oribe chawan that sold at auction late last year. It is an obvious, no-doubter genuine Momoyama kuro-oribe piece. Relatively few such early pieces have survived to present day, so to find such a terrific example on offer will generate some pretty fierce competition. This chawan attracted hundreds of bids, and sold for over 3.4 million yen. I'd love to have had it, but as soon as I saw how magnificent it was, I knew it would skyrocket, and I'd have no chance... This is the sort of piece that comprises an excellent ceramics collection all by itself. Cheers, Steve

-

I'll look forward to seeing your published results, Jean. I am most curious to know how the yakite shitate effect could be created with neither acids nor heat...

-

Ken, When you say that this "was sold as a Hon Ami Koetsu related piece," what exactly is meant by "related"? In any event, I can with some confidence tell you that this piece was not made by Koetsu. Virtually anything made by him is of immense cultural importance, fame, and value. He is considered by many to be the single greatest artist in Japanese history. So it is unlikely that one of his works would slip under the radar. Besides this, though, the bowl itself displays nothing of Koetsu's sensibilities, style, or techniques in the making of chawan. So again, I wonder what the seller meant by "related." Cheers, Steve

-

Kanayama? It sure looks much more like late-Momoyama/early-Edo Owari sukashi to me. There isn't enough of a yakite effect to suggest Kanayama, I don't think. The bold symmetry and strong, visually-heavy rim, together with the size and thickness all point to Owari sukashi, and without a more pronounced yakite effect, I can't see this as Kanayama. There certainly has been some good discussion on what, exactly, yakite (shitate) actually refers to. Some say it describes actual heat-treating as a finishing process, while others claim this can't be the case due to the way the metal would "behave" in such a process (i.e. the result wouldn't look like what we see in classic Kanayama tsuba). Instead, some argue, yakite refers to a particular effect (a "melty" finish) that is actually gained via the application of acids/chemicals to the surface of the metal. Not being a metallurgist, and not having been there at the forges of these smiths those 400+ years ago, I'm not entirely sure what to believe. Certainly we have seen examples of techniques in forging and/or finishing (in blades, say) that seem to have been lost to time, as later and modern-day smiths appear unable to recreate the effects those techniques would realize in the steel. So the possibility that tsubako of old may have had some way of manipulating heat (along with acids?) to achieve the yakite effect appears not entirely invalid, at least to me.