-

Posts

958 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

4

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Steve Waszak

-

That would be my thinking, probably, yes. I pretty strongly doubt that the tsuba you posted with have anything to do with the early Yamakichibei group. The revivalist spirit seems to have been ascendant in 19th-century Japan, perhaps especially in the Bakumatsu Period and a decade or two before that. I think it's quite possible, in fact, that some of the Yamakichibei and Nobuiye copies/forgeries we see in this time may have been inspired by the Norisuke utsushi of those smiths' genuine works, as much as by the works themselves. Given the high official status of the Norisuke tsubako, one might imagine that their making quality utsushi of the tsuba of illustrious early artists could have generated a significant interest in such pieces, which may have spawned something of a "cottage industry" in creating "unofficial homages" to those artists' works. Whether those making these copies made them as one-off pieces or in a sustained effort to make many of them and keep a business going I can't say for sure, but I suppose it's likely that both occurred. Steve

-

Hi David, I'm afraid I don't have all of those catalogues. I do have catalogue #6, and tsuba #6 in it is described as a typical Norisuke II work. The photo is small and details are hard to see, but the inscription on it does seem to be similar to those I provide images of above. However, with only this one poor photo in the catalogue to refer to, I would refrain from drawing any confident conclusions... Since I don't have any other of the Haynes catalogues besides #s 6 and 7, I can't comment on the other examples you speak of. I would agree with Curran, though, as I said, that many of the later Yamakichibei copies, carrying only the "Yamakichibei" inscription, and ascribed to one of the Norisuke smiths, are likely to have been made by others, and not the Norisuke, either for reasons of (a lack of) quality, or because of the political circumstances Curran notes, or both. I do not believe there was a true "later" Yamakichibei workshop. By this I mean that I believe that the original atelier died out in the early-Edo Period, and that later, unrelated smiths took up the "trade name" and used it to market their wares, beginning with "Sakura Yamakichibei," who is (erroneously, I believe) referred to as Sandai Yamakichibei. I'm not sure if you've seen the article I did on this group of smiths; if not, it is available in the downloads section here. 🙂 Cheers, Steve

-

I would agree: given the fact that the Norisuke tsubako were retained by the Tokugawa, it certainly seems unlikely that they would be making "unauthorized" outright forgeries of Yamakichibei (or other signed) tsuba. As you say, Curran, it is possible that the Tokugawa may, on occasion, have directed them to make such a copy, but the frequency of such an event would have been, I should think, very low. And so, I would agree further that the tendency to "default" to Norisuke-made forgeries for well-made copies of Yamakichibei work is misguided. It is clear enough that they did make utsushi of Yamakichibei works and those of other big-name makers, but as you say, Curran, these would very likely have been signed by them in addition to carrying any "Yamakichibei" inscription. All of the above makes very good sense to me. What I am then a bit perplexed by are some of the images from the book in questions, which depict a nearly identical rendering of the Yamakichibei name, and which closely echo the inscription on the actual tsuba whose photos I posted above (see photos below). In these images from the book, there are details especially in the way the "KIchi" and "Bei" ji are done which are not only fairly uniform from tsuba to tsuba, but which are also strong departures from the way these characters are rendered by the actual Yamakichibei smith(s). So, to my eye, they cannot be depicting genuine Yamakichibei guards, yet they also do not depict a Norisuke mei along with the "Yamakichibei" inscription. I suspect that what we might be seeing here, therefore, are simply drawings (not rubbings) of designs that the Norisuke smiths were looking to work with, rather than images of tsuba they already had made. Once the tsuba were actually made, then (probably) they would include their own mei along with the "Yamakichibei" inscription. Just sort of thinking out loud here... 🙂 As I say, though, the particular way of drawing these inscriptions in the images from the book very closely echo the inscription on the actual tsuba I posted photos of earlier (posted again below). The "Yama" ji is a little different, since the initial stroke is higher in the inscription on the tsuba than is depicted in the inscriptions in the book images, but otherwise, the "Yama" ji is quite similar, and the "Kichi" and "Bei" ji are as well. Again, all of the renderings of these characters from the images in the book are strong departures from the mei on actual Yamakichibei sword guards in key ways, The last two photos below are of the classic, Juyo tsuba made by (Meijin) Shodai Yamakichibei, and next to it a rubbing taken from the Norisuke book. Since this is a rubbing, and not a drawing, IF this is a Norisuke utsushi, we would expect to see a Norisuke mei (and/or other inscription content) along with the "Yamakichibei" inscription on the seppa-dai , according to what we agree is the likely practice of how the Norisuke would have worked (of course, we cannot see the ura on this piece, and I am unable to make out what the caption is saying below it, so perhaps there is such content on the other side of the tsuba). The details of the inscription on this tsuba rubbing are wrong in all three characters for the actual signature of a Meijin Shodai guard, so this is certainly not a depiction of his work. The rendering of the bird sukashi, too, is different (though an artist can certainly alter the way he presents the sukashi motif on a tsuba, of course). So here we have a rubbing of an existing tsuba which does not carry the mei of the Meijin Shodai (or that of the other four early Yamakichibei smiths) and yet also does not present with a Norisuke mei or other content indicating a "formal" utsushi. Might this be one of the "special order forgeries" that would be the exception, rather than the rule? David notes that this subject needs a lot more investigation, and I would certainly concur with that. 🙂 Cheers, Steve

-

Hi David, Thanks for that. I just looked, and the mei is quite degraded. What's left, though, clearly indicates (to me) that this is not a true Yamakichibei piece, and, following Curran's lead, I would say it is not a Norisuke work, either. I am not a Norisuke expert, certainly, but there do seem to be certain characteristics to a Norisuke inscription of the Yamakichibei name that are fairly steady. As can be seen in the photos I posted, plus in those pages in the Futagoyama Norisuke Ko that I referenced, it does seem that, some/much of the time, anyway, that far-right (third) stroke of the Yama character is missing. The reason for this may be (partly) due to the fact that on genuine early Yamakichibei work, that same stroke is "compromised" by the adjustments made to the nakago-ana in that area. But it is all three characters of the Yamakichibei inscription on Norisuke works that have tell-tale signs of the Norisuke way of rendering this signature, not just the Yama-ji. Cheers, Steve

-

Hi David, Would you by any chance have other photos of this guard, especially of the mei? I am reasonably sure that this is not the work of any of the Yamakichibei smiths nor of either of the Norisuke men. It would be helpful to be able to see more of the mei, though... 🙂 One curious aspect of the Futagoyama Norisuke Ko publication is that the photos of actual tsuba made by the Norisuke smiths as utsushi of Yamakichibei works show only one piece -- a Shodai Norisuke work on page 2 -- that includes a "Yamakichibei" inscription (on the ura, along with the Norisuke mei). The other photos of Yamakichibei utsushi (the actual tsuba) include the Norisuke mei, but not any "Yamakichibei" inscription. However, the section of the book that focuses on what I believe are rubbings of Norisuke designs shows quite a few Yamakichibei utsushi which are depicted to be carrying "Yamakichibei" inscriptions, but do not illustrate a Norisuke mei along with those inscriptions (see pages 56, 58, 71, and 76). Unfortunately, among the quality of the reproduction of these rubbings, the cursory style of the writing forming the captions for these rubbing illustrations, and my own limited ability in Japanese, I can't make out all of what these captions say. *It would be good, as you imply, David, to have a translation of this book. 🙂 Included here is an example of what I believe to be a Norisuke utsushi of a Yamakichibei tsuba. If you examine the mei on this piece, and compare it to those on the pieces illustrated in the rubbings on the pages I mention above, you'll see a lot of similarities in the way the respective mei are rendered, I think. Cheers, Steve

-

Hi Jean, No problem to share what we discussed, if you like. Cheers, Steve

-

First, a thank you to Barry for all the assistance (and for the encouragement) in getting the article put together. Much appreciated, Barry! Happy to help anyone with an interest in this particular area of tsuba appreciation and scholarship, to the degree that I can. I just want to emphasize, too, that the theory I put forth in the article was (and remains) the best understanding I have of the Yamakichibei group, but that my views could change as new information comes to light. Cheers, Steve

-

Okay, I've sent Brian the PDF. Fingers crossed that the formatting holds together. Cheers, all Steve

-

Below is a link to a thread on this topic. As Bob notes, I did a long article on the Yamakichibei group of artists for the JSSUS a couple of years ago, which I could add to the articles section here, if it is not too long, and if I can (figure out how to) load such a big article (with quite a few images). Not sure if that would be okay... Brian? Cheers, Steve

-

Which Of Your Tsubas Best Embodies The Wabi-Sabi Aesthetic?

Steve Waszak replied to lotus's topic in Tosogu

-

Excellent site. Highly recommended. Boris is great to work with, and he often has outstanding pieces. He tends to specialize in early tosogu (pre-Momoyama). Definitely worth a bookmark.

-

My understanding, though it could be wrong, is that if/when we see a "den Kanayama" designation, for example, what is being conveyed is that the piece in question is likely Kanayama, but that it also exhibits elements that point away from Kanayama; in other words, it's probably Kanayama, but is atypical in some way(s) or another. The atypical detail(s) may not be a "bad" thing, but simply represents a departure from the usual in some manner. My understanding here could be mistaken, though, as I say. Cheers, Steve

-

I don't really know much about late Higo, so no idea which generation on the Kamiyoshi. As far as having looked already, well, I saw the listing, but didn't open it, since the tsuba held no interest for me. I just default to "Kamiyoshi" when a piece looks late and Hayashi-esque. Oh, and I have no idea on the first tsuba Bob posted here...

-

In my view, that Yamakichibei is far, far away from being a Shodai work. Since we're in a "kantei thread" here, I'll say that I count at least twelve details in this tsuba that make it wrong for Shodai, and that's at least twelve. As for tsuba #2 here, my guess is Kamiyoshi.

-

Ah yes. That was it, Pete. Thanks.

-

Are you guys speaking of the Nobuie Tsuba book Markus Sesko translated? If so, I might suggest contacting him regarding availability of the PDF. David, I totally hear you on how tight funds are at the moment; many of us are feeling that for sure. But when you can, the Nobuie Tsuba book by Iida Kazuo is simply required reading for anyone with a serious interest in Nobuie. No other way to say it. One thing I will add, too, is that while some or even many genuine Nobuie works may not appeal to you now, with time and study (and especially if you can see and handle a few in person), they will grow on you. There is a reason genuine Nobuie tsuba have so long been considered by many connoisseurs to be the pinnacle of all iron sword guards. And there is a reason so many copies, forgeries, and homages were made following the original early Nobuie smiths.

-

David, Did you order the Nobuie book from Grey? Just curious...

-

David, Recently saw this tsuba on a Japanese Facebook site. Thought you might like to see it... Cheers, Steve

-

Hi David, Kosuke-tagane appears from time to time as a tsuba motif element. Here is an image of a Sadahiro tsuba I used to own (Nidai, I believe) that features this. I think I recall seeing at least one Nobuiye tsuba (futoji-mei) that utilized this feature as well. Cheers, Steve

-

Oldest piece of Japanese art

Steve Waszak replied to kissakai's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Hi Grev, It really is even more beautiful in hand, I must admit. And as I mentioned, at least one person who is as close to an expert on truly early tosogu has said he'd put it a lot earlier than I have/had it. He told me that a late-Kamakura to Nambokucho date is very possible, but no later than earliest Muromachi. So maybe a 14th-century date is a good dating for it. Anyway, given the subject of this thread, many other members here have earlier pieces for sure. Cheers, Steve -

Sounds good, David. Talk to you soon. By the way, here's a link to the book in question on Grey's site: https://www.japaneseswordbooksandtsuba.com/store/books/b952-nobuiye-tsuba-full-translation

-

Oldest piece of Japanese art

Steve Waszak replied to kissakai's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

I am not very knowledgeable when it comes to pre-Momoyama tsuba, so I am happy to defer to those who are. From what you say about Sasano, Grev, it seems this may even be as early as Kamakura Period, then. I suppose Nambokucho to early-Muromachi is the "safer" bet. -

Hi David, Nobuiye is, of course, a complicated and contentious subject in tosogu studies. For anyone with a serious interest in pursuing this specialized area, I would highly recommend acquiring the Nobuiye Tsuba Shu by Iida. This book focuses entirely on Nobuiye, and the rubbings, photos, and essays on the appreciation, study, and evaluation of Nobuiye works are especially valuable. The essay by Katsuya Toshikazu is particularly excellent, offering extremely detailed analysis of Nobuiye sword guards, including tightly-focused examination of the sugata, the hira-ji, and of course, the mei. I believe that if you get this book and read the essays, you'll have a better idea about which Nobuiye may have made your tsuba. In my opinion, this is an early piece, but it is not by one of the two great masters comprising the first generations. Several things lead me to this conclusion, including aspects of the sugata, the hiraji, and the mei itself. While I agree with you and Dale in principle regarding the fluidity of artists' signatures, three things I think should be kept in mind. First, there is, perhaps, a meaningful difference between the way a painter/graphic artist may sign his or her works -- using a a brush or a pen -- and the way a metal smith might, using a chisel. The latter, of course, is a much slower process, and allows for much more time to be taken to locate with precision where the strokes will be placed, their angles, depth, length, relation to one another, etc... Second, in a culture as "calligraphically conscious" as the upper-class Japanese (for whom Nobuiye tsuba were certainly meant), there may be (have been) much greater sensitivity/awareness in general as concerns the presentation of a mei. The very fact that these early tsuba were among the first even to be signed at least suggests the possibility that mei presentation mattered to some degree, and so, it seems rather unlikely to me that mei would have been "slapped on" cavalierly. Finally, even within artists' signatures' variations, there are often certain consistent tendencies that remain among the evolving iterations. It is part of the "art of mei study" to become sensitive to how these manifest in a given artist's work, subtle though they may be. In your tsuba, David, I see at least three elements of the mei that strike me as a bit "off" for a would-be futoji-mei signature (it is clear that the mei is of the futoji-mei variety, and not that of the hosoji-mei/hanare-mei Nobuiye). While any one of these three could be brushed off fairly easily as anomalous, two bring more doubt, and all three have me deciding, based on mei alone (which I certainly wouldn't consider by itself), that the sword guard is not a true futoji-mei tsuba (That it could be the work of a student of a later (early-Edo) Nobuiye workshop, however, seems entirely plausible to me). Of the three points of concern, one is present in the "Nobu" ji, one in the "iye" ji, and one in both. I am happy to discuss this further with you, David, so please feel free to PM me if you like. We could also discuss certain "issues" with the sugata of your tsuba, as well as of the hira-ji. I like your tsuba; I think it's a good early piece, and the subtle workmanship of the kikko pattern on the hira of the mimi is a good sign. It could be a futoji-mei work, but as I say, I have my doubts. Cheers, Steve P.S. Below are some examples of futoji-mei Nobuiye tsuba, just for reference...

-

Oldest piece of Japanese art

Steve Waszak replied to kissakai's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

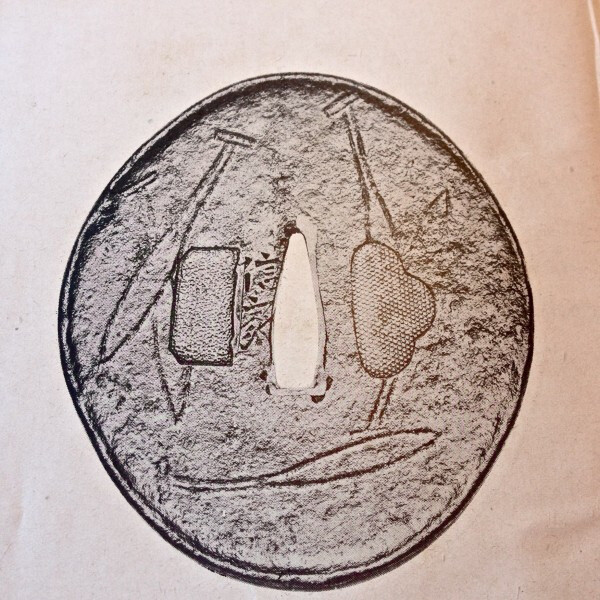

I think my oldest piece is this one, a bronze tsuba dating conservatively to mid-Muromachi I believe, though at least one person with far more experience on very early tosogu has said it could be or even likely is Nambokucho/early-Muromachi. Bronze sword guards are not very common, and they would seem to have been in favor in earlier (than mid-Muromachi) times. At 4mm in thickness, this tsuba is very heavy, has a deep patina, and as can be seen, presents with plenty of remnant black lacquer.