-

Posts

978 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

4

Steve Waszak last won the day on September 8 2025

Steve Waszak had the most liked content!

About Steve Waszak

Profile Information

-

Location:

San Diego, california

-

Interests

iron tsuba, up to early-Edo

Profile Fields

-

Name

Steven Waszak

Recent Profile Visitors

3,676 profile views

Steve Waszak's Achievements

-

Steve Waszak started following Itoh Mitsuru - Nobuie , Introducing NihontoWatch: The Entire Market in Your Pocket , Passing of Brian Klingbile (Winchester) and 4 others

-

This sword is now SOLD.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

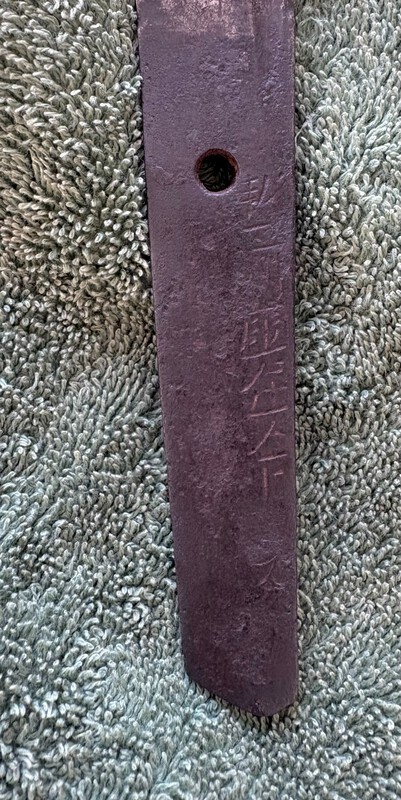

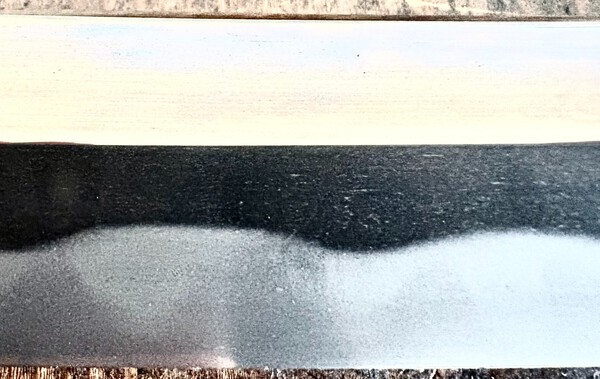

Offered here is a powerful signed Shinto wakizashi by Echizen ju Shimosaka. The blade is in excellent polish (keisho, I believe), and presents with many highlights. There are kirikomi in the mune in a few places, perhaps an indication that this sword saw some active combat. Measuring almost 55cm (21.5 inches) in length and 3cm wide at the machi, the blade is approximately 8mm thick at the munemachi. Two NBTHK papers accompany the sword, both affirming the mei as that of Echizen ju Shimosaka. One is an NBTHK Kicho Token paper, while the other is NBTHK Tokubetsu Kicho Token. While the wakizashi comes in shirasaya, there is also a koshirae, complete with tsunagi. The habaki is silver or silver foil. Priced at SOLD, plus shipping.

-

Also agree with Curran and Okan. To me, it looks mostly like a late (modern?) work "inspired" by Owari sensibilities. The workmanship and finished look of the piece, though, do not conform to Owari sukashi, Kanayama, or Yagyu, in my opinion.

-

Hi Grev, Yes, my copy is signed. I did get the translation along with the original, but on the Itoh's website, they do make it pretty clear that the book is accompanied by an excellent translation, so, I'm not sure how this disconnect for you occurred. Sorry that happened. But get the translation: it's worth it.

-

Really appreciate (and try to share) your approach, Curran. Moving from great to sublime is hard, not only because great pieces are, well, great, but also because it takes so much focus, discipline, and patience. I believe it is worth it, though. In my experience, one great piece is worth ten good ones, and one magnificent masterwork is worth ten great pieces. Quality over quantity, when both cannot be had. Eagerly looking forward to what you'll acquire, Curran, and really pulling for you.

-

Sorry To Report

Steve Waszak replied to Grey Doffin's topic in Sword Shows, Events, Community News and Legislation Issues

Very hard news. More hard news on top of so many recent and major losses in the community. I knew Richard, having seen him at San Francisco sword shows several times, and visiting him at his home in Portland, Oregon, where I saw the elaborateness of his photography set-up. Good guy. He will be greatly missed. RIP, Richard. -

I have this book: HIGHLY recommended for anyone with an interest in the Nobuie smiths and the context out of which they arose. This is a lavishly done publication, highly readable, with beautiful black and while life-size images of the pieces illustrated. We desperately need more scholarship on this level in our field. Superb.

.thumb.jpeg.4c8809361b683287ab304c4f325c4e21.jpeg)

.thumb.jpeg.25b3e3ed894ca7b2d41fcaf6bc632065.jpeg)

.thumb.jpeg.9ab7857bc2bd65221b38980668af0b24.jpeg)

.thumb.jpeg.2627ae8b95243dd3939b99ba2e52db9c.jpeg)

.thumb.jpeg.87a8359c33708a458680cfb9d04d2030.jpeg)

.thumb.jpeg.cec2f856dcac7deb1d7968de1a3a7305.jpeg)

.thumb.jpeg.b970e5b3ceaafd55aa22fd4fe087af40.jpeg)