-

Posts

3,091 -

Joined

-

Days Won

78

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Ford Hallam

-

Adam, try re-reading my posts more slowly....and please stop misrepresenting what I've said. The only one being misled by your strawman arguments seems to be you. I trust my posts are clear enough and self explanatory to any other interested members and thanks to the kind and amusing responses 😎 Glad to be of service.

-

Perhaps I ought to add at this point in the discussion that if your suspected shibuichi pieces are a chocolate brown colour then they are most probably not shibuichi but rather either nigurome (copper with the addition of shirome, itself a spiese, or refining byproduct, containing arsenic and antimony, and which tends towards a reddish brown) or a copper alloy with literally only 1 to 4 percent silver present, which would fall outside of the generic shibuichi group. Of course, an accurate identification of an alloy would only really be possible with a chemical analysis. This brown patinated alloy has previously not been documented but is essentially a sort of shakudo but for the substitution of silver for gold. I actually predicted this alloy might be more commonplace over 20 years ago when I had a piece by Shoami Katsuyoshi analysed and which contained one such sample. I then found more samples in the surveys I carried out at the V&A. It would appear to me that, based on the quality of the pieces I've identified, that is may have been a cheaper substitute for regular shibuichi, when used as the ground material, given the very small amount of silver used. I would suggest this particular alloy goes unnoticed often when it shows up as a small detail in an iroe composition, like as a staff or other 'wooden' object.

-

Barry, I'm now pretty keen to get the book out too. It's going to provide a few points that will no doubt require some rethinking in terms of dating of certain non ferrous pieces, so that'll be fun to watch And, as I describe in the film I linked to, shibuichi is actually mistranslated as being a 1/4 alloy. One important Edo period text explicitly describes it as a 20% silver and copper alloy ,and that being the origin of it's name. This is further supported by numerous analyses I've carried out. There are in fact two, three at a push, distinct groupings of shibuichi alloy. The 20% ball park composition (actual analysis results show a little variation, around 2 percent either way) is by far the most common. The only other trace metals we find are lead and gold. The lead, usually less than 0.5%, is a residue of the copper refining process and the gold is inevitably residue in the silver from it's refining. Again typically less than 0.5%. Neither of these trace metals alter the working and patinating properties in any significant way. The book will provide exhaustive data analysis that accurately provides a pretty clear picture of the whole Japanese alloy pallette.

-

No, I can't say I do know everything...even in my chosen speciality of fine metalwork. But to suggest that I'm just like you, and 'still learning' misses a pretty significant difference.🤔😉 What I offer is based on my 40 years of craft specific experience, literally 100's of XRF analyses and 100's of restoration jobs on some of the very finest Japanese metalwork available (not ebay dross). There's nothing that immediately comes to mind with regard to shibuichi that remains vague or a mystery to me. I absolutely would not say, at this stage, that there is anything lost from how shibuichi was made or worked, certainly not in my understanding of the subject. And to reiterate, this is based on 40 years experience as a professional Goldsmith, training in Japan, countless hours of scientific analysis and 1000's of pages of textual research. I will state unequivocally that when newly made and traditionally patinated shibuichi alloys exhibit a grey tone. The exact shade of grey, nezumi-iro, is dependant on the actual silver percentage AND how long the alloy mix was held at liquidus, or allowed to stew when fully melted. For a detailed explanation on the making and processing of shibuichi you can watch this film we just posted last week. Shibuichi exhibits a finely granular surface structure, a bit like a stone wall, with particles of silver seemingly embedded in a copper matrix. This structure is what gives rise to the characteristic 'nashiji' surface effect in shibuichi. It also means that when the silver and/or copper particles are acted upon by pollutants they can each develop different oxides, chlorides and sulphides. Silver can develop a layer of silver sulphide and then the shibuichi turns very dark, almost back. Or, it may develop silver chlorides, and turn the patina decidedly green. The copper component can become redder or blacker...,or even more green than the tone silver chloride causes, at which point there's a real corrosion problem, again, depending on the pollutants in the immediate environment of the shibuichi. I've worked on a number of very fine shibuichi pieces, Unno Shomin, Unno Moritoshi, Kaigyokusai Kazuhisa et al, where they've been needed to be dismantled to some degree. Panels in frames, boxes, stands with feet etc, and often found that their lovely greenish or brown tinted shibuichi patina wasn't in evidence in the areas that had been covered or otherwise protected from the atmosphere or handling. On those, untouched, surfaces the patina was unchanged and perfectly grey, and often startlingly fresh, as though done the day before. As a specialist, with the additional advantage of greater scientific and metallurgical insights (I stand on the shoulders of others here) than those that were available to Edo workers I'm advantaged in having a better understand the mechanisms by which all of this comes about. But, after a couple of hundred years of using the alloy Japanese metalsmiths of the Edo period knew what effects were stable and what would likely happen to pieces over time. I've even read accounts in period diaries that mention the need to have tosogu periodically refinished, so some degree of ongoing maintenance was not uncommon but deliberately applying effects that would lead to damage or the 'muddying' of the work's visual impact simply isn't something that I've found any evidence for. To summerise, shibuichi is grey, of various tones dependant on silver content. But, beyond the exact control of the maker the final patina colour can also be affected by the melting time and conditions. Any other hints of colour are the result of later interactions between the surface patina and immediate environmental conditions. Some of these later developments in the surface patina are stable, while some are ongoing and will result, eventually, in significant surface degradation. Adam, I'm also very curious to know why you think that "Some of the skills are also lost." I assume this is with reference to the subject at hand, shibuichi, or why else would you mention it?

-

I wouldn't do anything at all to it. Basically because it's a modern piece, and because it's 'pretending' to be Edo period it's a fake. It's copper, and the colour is nothing like an authentic shakudo patina, more likely some or other industrial process. It may actually simply be a contemporary hobby pieces, and as such perfectly honest. But, as far as Edo period kata-kiri work (the actual chiselling technique) goes it not skillful at all and the carver really didnt understand how tigers are carved in this style at all. Both points strongly suggest a relatively modern and in-expert manufacture I'm afraid.

- 19 replies

-

- 1

-

-

Tanto What do I have here?

Ford Hallam replied to Guns Knives and Swords's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Let me start by saying that Guido Schiller is a huge wind up merchant and is probably not in any way good for my health. He 'generously' sent me a link to this thread suggesting it'd amuse me. So...here I am🤪 I had a good look at the images before reading any opinions. I formed my own 'take' on the set completely independently of those posted previously here. My first impression, and it remains so, it that the entire koshirae is original. The copper metalwork workmanship is unmistakably 'en-suite'. The only feature that stands out, in an awkward way, is, to my eyes, the rough file marks and outline of the kogai atari on the fuchi. The same feature on the other side, for the kozuka, appears to be neatly and delicately shaped and filed. But, significantly, it also clearly has traces of silvering still present in the textured area. This is quite absent on the other side, the rough one. Now, as has been pointed out, there's no way copper implements like the kogai and kozuka, even the steel blade, could create that sort of 'yasuri-mei' pattern in copper. So we can safely rule our wear. Adam (Babu) stated quite emphatically, early on in this thread that This is incorrect, as the descriptive term 'yasuri-mei' might suggest. In fact, a filed ground is a fairly common feature on tosogu. We see it most frequently on the soft metal liners of hitsu-ana on tsuba, for example. It appears specifically to have been applied where there was a possibility of some 'metal to metal' contact. This type of finish hides well minor scuff marks that would otherwise be glaringly obvious and unsightly on a polished ground. So we have one anomaly in an otherwise perfectly matched and well preserved period piece. I would suggest that the absence of any traces of silvering might mean that someone worked on that area sometime after the whole koshirae was first completed. The work carried out is clearly not as careful or skilled than the original work. The 'yasuri-mei' on the untouched side are very even and quite fine, and the out-line is neat and a pleasing curve, and was silver, which would have echoed the moon on the habaki and looked quite stylish when the kogai was withdrawn, a nice 'surprise'. To create all of that elegantly takes a great dal of hand skill, experience and attention to minute detail. Whoever attempted to rework the other side simply wasn't good enough to match the level of skill required. They lost control of the outline, the shape became less than elegant, and the file marks are uneven, with occasional lines noticeably deeper, which in turn creates a less refined effect. And the silvering wasn't re-applied. We can speculate as to why this additional work was carried out, possibly there was a blemish of some sort, a knick or some verdigris for example...I've seen far worse as the result of well meaning restoration by inexpert restorers. There you have it, my opinion, for what it's worth, and including previously unnoticed and crucial evidence, to wit the traces of silvering. 🤓 I should like to add that no amount of experience as an engineer, in modern times, will provide any insight at all into the subtitles of hand working copper, or any of the metals, ferrous and non, at this level of finesse in the Japanese tradition. So can we please all agree not to toss irrelevant credentials about on this forum like they might actually mean something? They don't, and are only being used to claim some authority where none exists. I'd go so far as to say that it's a bit like claiming special insight into Rembrandt's technique because you've been a painter and decorator for 40 years. I bet some of you wish now that you'd let sleeping dogs lie...🙊 oh, and just for the record, as part of my training to become a master goldsmith...a real qualified one with papers 'n s**t, I had to study metallurgy, and gemmology. But the most valuable skill one learns on the way to becoming a master craftsman, like Drurer, Da Vinci, Bernini, Holbein et al, is that of seeing....and then trying to understand accurately what it is you see.- 95 replies

-

- 12

-

-

-

-

Kakihan are stylized monograms that are loosely based on a kanji, sometimes. There are, if memory serves, three basic types, one type called ni go tai is composed between two horizontal strokes, for example. As for photographic reference books of mei and kao the standard reference would be the Shinsen Kinko Meikan, not cheap but essential if you plan on becoming a serious student and collector. https://www.japaneseswordbooksandtsuba.com/store/books/b879-shinsen-kinko-meikan

-

Hello Adam In my experience Joly's references are useful in identifying an artist but I would suggest that his illustrations, while accurate in terms of general form and strokes etc. , are not enough to confirm the authenticity of a particular piece.

-

Second one brings to mind Daigoro to me.

-

Morning Gents, Peter's post properly made my laugh out loud, my muesli nearly went up my nose Thanks again for the kind comments on the tsuba though and the renewed interest. It just so happens that over the past month or so we've been putting out a free "how I did it" series on the making of this type of piece as my offering to help keep sane during this time of crazy. It's in 12 parts on my Patreon channel here: https://www.patreon.com/posts/36667789

- 15 replies

-

- 10

-

-

Never Natsuo, it's well documented that he was a very fastidious man with extremely genteel ways. Drunk? never! Piers has correctly identified Mr K, his book of drunken sketches would clinch that. Kawanabe Kyosai, the demon painter, had an English student, Josiah Condor, who wrote a very useful book on Kyosai's teachings and in which we learn a fair bit of his character. I think perhaps the story of his only working drunk is a bit exaggerated. J. Conder, Paintings and Studies of Kawanabe Kyosai, Yokohama, 1911

-

...or by Jingo, or Kaga Yoshiro, or or

-

While using ivory or bone to rub away rust is a common approach (I don't always agree that it won't scratch the underlying patina or iron though as the rust can be harder but that's another debate) I would suggest that in this case it might be unwise. The nunome overlay is often quite delicate once rust gets going so it can easily be lost during cleaning and restoration. Similarly the soft metal inlays, faces and hands etc, seem to be in good shape in terms of the actual sculpting so there again great care must be taken not to lose any of that original form while dealing with oxides and verdigris. I only mention these points here because this one looks to be a pretty decent example, signed, and as yet untouched by over-enthusiastic hands. A lot of original information is too often lost or overlooked when pieces are 'cleaned up'.

-

Dave, there will always be arseholes wherever humans interact, and there will always be some who just rub others up the wrong way. Your supercilious comment as to why you don't post your pieces here was uncalled for. And frankly speaking, as you seem keen to be blunt, I often feel like not bothering here too....when I read comments like yours. So, touche. Brian is a personal friend who does a great deal for the collecting community served here for very little thanks, he certainly does not deserve shitty feedback.

-

Roger, you very succinctly sum up exactly my own conclusions.

-

I would have to take exception to this claim. There is to date no evidence to support such an early date for the use of brass in Japan. The most likely, and evidentially supported date, would be closer to the early 17th century, ie; 1600's. At an absolute earliest date it might be argued that as soon as cementation brass was produced in quantity in China in the late Wan-Li period (circa 1575) some enterprising trader bypassed official government operations of production and control and managed to supply Japan. But then you'd have to provide some evidence for that story A further technical point that is not considered is the development of wire drawing plates. Prior to this technology being used wire was produced by cutting thin strips off a sheet (with shears) and then either rolling in more round, like bread dough, or twisting it. I've seen evidence of strip inlay that could be mistaken for round wire so in the absence of any information or evidence of drawing plates in pre 1600 Japan I'm further convinced that all these brass inlay pieces are essentially Edo period productions. The plate might be older but not the brass or technique.

-

Thanks Jeremiah, yes, we've committed to putting out as much as we can during this lockdown to help other keep sane. It's too late to save my sanity though.... This is the start of the present series; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=79wVi94NKNQ

-

Hey Brian, there's so much to talk about that'd be awkward to write about so I've decided to make a film presentation of that sheet. I'll get it completed this week and post a link here.

-

Hi Ken If memory serves they were made by shiro-gane-shi, lit. white metal workers, or silversmiths and they were essentially functional parts like seppa. It's a little amusing to see how the habaki has been elevated so much in modern times, perhaps because of the general decline in quality in Japan of the overall tosogu scene. That's not to say some habaki are not beautiful art works but those antique ones are almost inevitably made by tosogu-shi. Of the finest modern habaki I wouldn't call them art though, rather fine craft...especially when you know the techniques being employed

-

Technically no, tosogu are the decorative elements of swords mountings whereas habaki and seppa are regard as being purely functional elements, made by shirogane-shi, class of metalworker below the more creative ranks. At no point in Edo period metalworking culture were the makers of seppa, habaki or any of the basic blanks of tsuba and fuchi kashira regarded as anything more than relatively low level artisans. Having said that, of course we've all seen the occasional fancy arty habaki or seppa set but these really are the exceptions.

-

Sorry to be the bad cop but to my eyes this is not at all like any of the various types of work Mitsuoki is known for. The tsuba looks more to be Kinai or maybe Bushu. The mei is not convincing at all, either, I'm afraid. The work is not too bad but I suspect the signature and inlaid ' seal' may be a much later addition

-

In my opinion this is not Edo period but the work of a 20th century amateur, albeit a fairly skilful one. Main give-aways to my eyes would be the unconvincing kogai-hitsu. Very odd 'sombrero/flying saucer' shape and no apparent awareness of how the inner edge aligns with the saya opening for the kogai itself. The inscriptions are really very poorly written and lack any sort of evident coherence. The overall feeling is of a mei on a lower end gendai-to. If memory serves I've seen a few by this hand in recent years. The nakago-ana is also unconvincing as are the punch marks. It certainly doesn't look like a blade was ever mounted in it, so why are they there? other than to suggest use and fool us into thinking it is a real antique.

-

Thank you, Gentleman, your observations are providing me with more to think about too. At this point I would like to suggest that you try and see the negative, or 'white' spaces first. This is a way of seeing the composition afresh, and a means of more clearly starting to asses the balance and interplay between the spaces and the design. My mother, an accomplished artist, used always to refer to the negative spaces in sukashi tsuba as either happy or unhappy spaces. Are they interesting in their own right? are they 'useful' in the way they echo and contrast the shapes that are left? Perhaps look at the design upside down to see the white parts, or squint until your focus shifts from the actual tsuba to the spaces instead. The second point, already noted by many of you, is the actual lines that make up the design. Are they interesting and 'telling a story' in each segment? A good composition or design ought not to have any weak or pointless lines or shapes, every detail must be doing something.

-

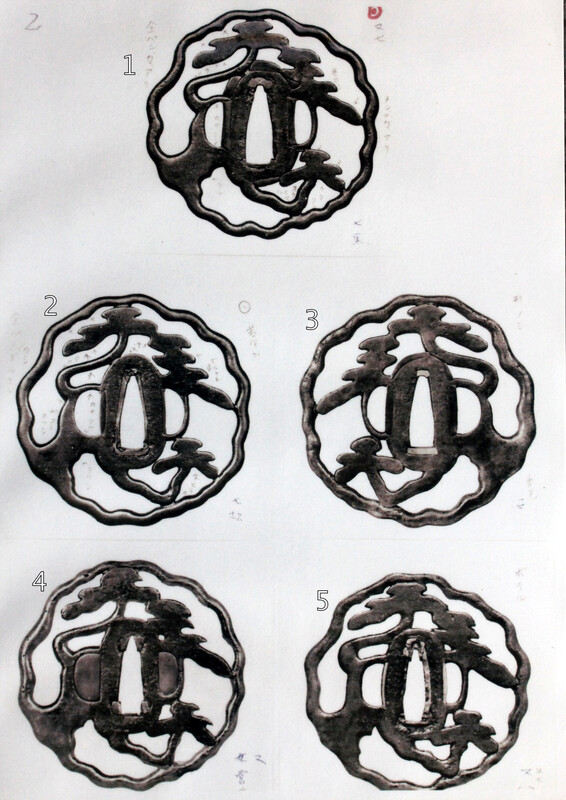

A few years ago Ikeda Nagamasa Sensei, the sword polisher, gave me a series of study sheets that his father, the scholar Ikeda Suematsu, used to use when lecturing on aspects of tsuba appreciation. In response to a recent thread on a similar pierced design I thought this particular sheet might be a good starting point for some considered analysis of the design. I don't want to say much more at this stage but rather would invite you to make your own observations and comparisons. Feel free to say what you see and think about what elements or particular tsuba most appeal to you. Click on the image to see a much larger version. It would seem tsuba no:3 was perhaps an experiment to see if the design worked flipped over as a mirror image. What do you think, does it work as well? And for comparison here's the same design in a more usual alignment.

-

Pete, not to simply be a contrarian but I have never been able to square the notion that age, with regard to tosogu, is in any way related to finer craftsmanship. This general notion seems to suggest that because standards are perceived as having slipped over time therefore fine work is, de facto, earlier. Surely the obvious self referencing fallacy is self evident here? When faced with this notion I'm always reminded of something Shoji Hamada, the first National Living Treasure potter, said about his work and his habit of not signing it. He said his poor work would be attributed to his students and their best work to him..... When I start making tsuba and not signing them one of my students will have received my final benediction ....but not yet