-

Posts

3,242 -

Joined

-

Days Won

99

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Guido

-

Seikadô exhibition

Guido replied to Guido's topic in Sword Shows, Events, Community News and Legislation Issues

Unfortunately yes. :lol: Yasutsuna is the earliest sword smith ... grooves make a sword more resistent to bending ... how much more can someone [self-deleted profanity] an article who obviously had the chance to get it straight from the museum/curator? -

"LordThanatos", Brian - the host of this forum - asked you nicely to stick to the forum rules, signing with your real name. I, as a moderator, hereby repeat this request.

-

Seikadô exhibition

Guido replied to Guido's topic in Sword Shows, Events, Community News and Legislation Issues

I fully agree. For those not being familar with it: 100 important swords on double pages, one page showing high quality b/w photos of the entire blade, the Nakago and Monouchi, second page with a description and an extremely detailed Oshigata of the Monouchi. Some color plates in the front of Koshirae and fittings. English index. -

IMO there's not that much of a difference between swords and pottery (and possibly Sumi-e and a few other traditional crafts/arts). I see swords and pottery as close enough to compare them; they have at least one thing in common: fire is an element that can't be controlled 100%, and the outcome of exposing an object to it can be predicted only to a certain degree. The function of a Chawan is to hold tea, and the function of a sword is to cut. The better the craftsman, the better he will install this function. People who want to quench their thirst, or people who practice Tameshigiri and/or IaidÅ, are satisfied if the functionality is average or better than that. Controlling fire and clay / fire and glaze better than his peers, and therefore making the object to function better and looking more pleasing, is the achievement of a great craftsman. If a tea bowl or sword doesn't only properly work as such, but is also aesthetically appealing, we're entering the world of art. Controlling all of the above, making the object functional and beautiful, and still giving the bowl or blade the appearance of being natural, or even random as a result of the powerful, unpredictable element of fire, is the hallmark of a truly great artist. I call it the "Japanese garden effect": controlling nature in a way that makes the result looking more natural than nature itself. A contradiction, perhaps, but it works for me. This genius is seen, for instance, in the works of Masamune, and I think that's what Reinhard was talking about. It leaves me in a state of (pleasant) emotional shock, and swords like that indeed have kind of a presence. OTOH, my feelings could be the result of residue of the stuff I smoked back in the seventies/the army, who knows. Although beauty certainly is in the eye of the beholder, educated people usually find a consensus about aesthetics pretty easily. Some art forms, and especially traditional Japanese art, however, can't be properly judged and appreciated without knowledge of its cultural context and its technical aspects. That's where studying the subject in-depth comes in, and that's where many people give up, finding it too tiresome. Still being intrigued by the romantic aspect of the "Samurai Sword", they hang on nonetheless, concentrating on topics where, they think, matters of opinion are discussed. Once we have a solid basis of being familiar with all the technical aspects, roads, schools, styles etc. we either can stop there - becoming a collector of superior craft objects (and there's absolutely nothing wrong with that!) - or we can "advance" to the twilight zone of art appreciation. *Now* we can discuss matters of taste (for example, I personally prefer Sadamune to Masamune), but at least we're on the same page. Unlike going uuuh and aaah over the Hamon of a generic Sukesada of the Sengoku period because it looks like crabs claws. (Heck, I *love* crabs, preferably with a little lemon, but I don't care for their image on my sword. In case this caused some offense, I apologize to all crab lovers, both sword and animal related ones.) Do I really know what art is? Maybe, maybe not. Actually I'm rather convinced that I do. But then again, I'm neither really sure of the side-effects of the weed back then, nor all the booze after it. Please feel free to make this your Zen quote of the day.

-

Seikadô exhibition

Guido replied to Guido's topic in Sword Shows, Events, Community News and Legislation Issues

No separate catalog, all their swords were already published in the book "SEIKADÅŒ MEITÅŒ HYAKUSEN é™å˜‰å ‚å刀百é¸" (which unfortunately is out of print now). Their address and phone number is on the web-page I provided a link to above, but to my knowledge there's no fax # or e-mail address. Sorry. -

Finally....a truly functional tsuba

Guido replied to Ford Hallam's topic in Auctions and Online Sales or Sellers

I am still in Tokyo, and have been to that shop quite often. In other words: I'm quite proud that my brain has a build-in short-circuit that prevents me from consciously looking at kitsch like that. -

James, I don't know who the polisher is you contacted, but many of the "regular" ones are struggling to make a living, and might polish a blade that isn't worth it. I have a feeling he wants to put an artificial (i.e. "polished") Hamon on it. I would advise against it; among other concerns, it's an investment you'll never recover. And since his opinion on the condition is significantly different from that of other Togishi, it's all the more a reason to politely ask him to return it to you. Just *my* opinion, your actual mileage may differ.

-

Finally....a truly functional tsuba

Guido replied to Ford Hallam's topic in Auctions and Online Sales or Sellers

Aaah, the famous Owari Sukashi crab Tsuba from the Muromachi period (so much for the description)! Now I wonder even more why I was blocked from viewing it on eBay ...? -

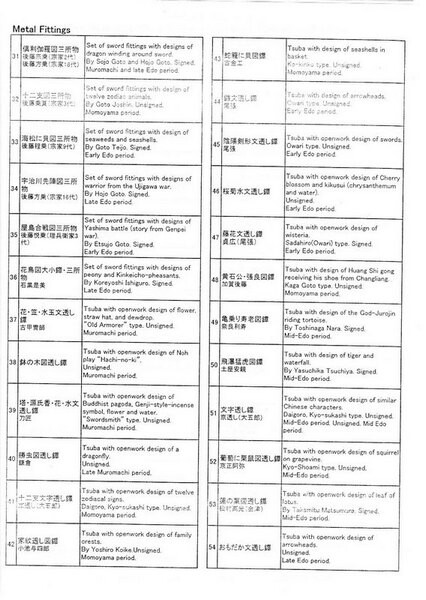

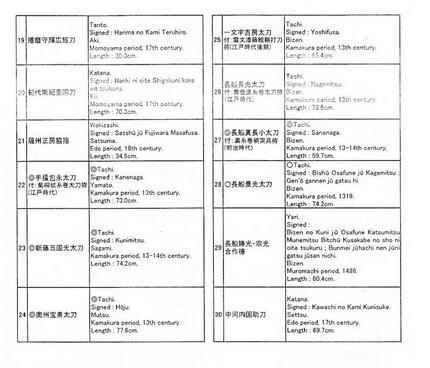

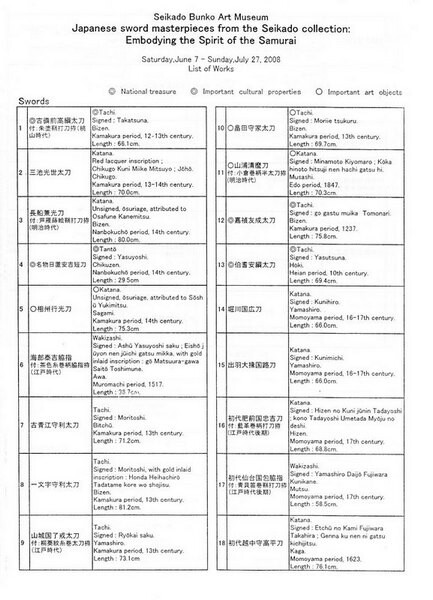

The Seikadô museum currently shows an exhibition of swords and fittings; it'll end on July 27. Living in Japan for a long time, I'm pretty spoiled when it comes to high class exhibitions, but this one really is a *must*, and rivals the best NBTHK exhibitions. Attached is a list of items on display (no less than 12 Kokuhô, Jûyô Bunkazai and Jûyô Bijutsuhin!):

-

Finally....a truly functional tsuba

Guido replied to Ford Hallam's topic in Auctions and Online Sales or Sellers

I almost don't dare to ask what kind of Tsuba this is - 3rd Reich? -

Here's an excerpt from an article on collecting Nihontô I wrote; it triggered the same kind of response like some comments in this thread when it was published in the JSS/US Newsletter:

-

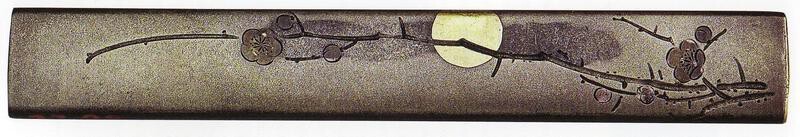

After the "Kantei" of this Tsuba - which went off to some quite interesting topics - I thought I might finally show a few photos about its restoration (if it can be called that). When I bought it, the silver was tarnished, and it had a sticky coat of grime which I suspected to be some sort of wax. After cleaning it with pure alcohol, I gently wiped the silver parts with a Q-tip I had put in a box of "never dull" the day before. Grime and discoloration were gone, but a kind of silverish halo appeared under the moon. It became evident that someone had cleaned the silver, probably using some fine steel wool or another mild abrasive. I applied some Baldwin's Patina (http://www.reactivemetals.com/Pages/rmspat.htm) to that area, which patinates copper but not silver or gold. Although the result looked quite acceptable, I contacted Ford Hallam and asked for his opinion as well as suggestions about how to prevent the silver from becoming black again. Here's an excerpt from the e-mail he sent me (quoted with his permission): Picture # 1 shows the Tsuba as illustrated in the magazine "Koetsu" in 1977, and pic # 2 in the NBTHK Kanteisho from 1992. It looked like in pic # 3 when I bought it, and pic # 4 shows it after I cleaned it. Pic # 5, after "repatination", was taken yesterday, and gets as close to its true color as my limited skills with a camera permitted; it also gives a good impression of the Nashiji effect Ford mentioned.

-

You mean the book where he says that Kinkô never understood the true meaning of Tsuba, and wasted their talent on fancy surface decoration? 鑞 is "wax", as in Kuro-rô-iro, the deep glossy black of many Saya. The meaning of 鑞 and 朧 is, IMO, close enough to - together with the same reading - encouraging a mistake in choosing the wrong character. However, I wouldn't be surprised if it's indeed an alternative way to write the *same* thing. I've seen stranger things in the world of Nihonto ...

-

The On-yomi of 朧 is RÔ, the Kun-yomi OBORO; I have nothing to back it up linguistically, but from the belly I would read it On in connection with 銀 GIN. According to Nelson, it means "haziness, dreaminess, gloom".

-

I'm thirsty, too, but for a different reason. Kind of "let's have a beer after a job well done". :D I read the description in the Kôza, but found it hard to digest. Ford's detailed explanation isn't something you easily find in books, and a valuable contribution to the study and understanding of sword fittings. Keep it coming, Ford!

-

Interesting points. Actually I never thought about that, because I always assumed that Katana are the most difficult to make - maintaining the quality of the Jitetsu and Hamon on a rather long piece of metal - and Tantô are a challenge because it's difficult to not overload them, but make them interesting nonetheless, and all that on a very short piece of metal. In my understanding it's therefore a combination of craftsmanship and artistic ability that make Katana and Tantô more desirable than Wakizashi; the latter are easier to forge than Katana, and don't give the smith the headache of the limited space that Tantô do.

-

Oops, lokks like I have to work on my English, my eyesight, or possibly both ...

-

Now, I'm not delusional, and clearly see the differences in quality of the KodÅgu in the scans in comparison to my Tsuba. I like it very much nonetheless, especially the "modern" feeling it has to me. I bought it for what it is - as Curran put it, "a nice little Tsuba" - and not a piece equal to the masters themselves. But at least it isn't one of those "miniature iron steering wheels" ... Oh, and before I forget it: I sometimes see on very late, e.g. Meiji period work, the typical discoloration on the Seppadai suggesting that the Tsuba was mounted. Especially on otherwise pristine Tsuba, and taking into consideration the time they were made in, I wonder if that really comes from wear, or if we're looking at an artificially introduced feature.

-

The description says (loosely translated) that this artist is not recorded, but looks like from the GotÅ IchijÅ Mon. Funada Ikkin had a student by the name of Kazuaki 一明, and Norikaki 則明 may have been Kazuaki's son or student. In any case, the author goes on, it is quite clear that the Tsuba is made in the tradition of IchijÅ. Mr. Homma wrote that in 1977, and I don't know his reputation, but he obviously considers the name an important factor in his evaluation. BTW, in the above scan, and the Hozon papers from 1992, the Hitsu-ana was plugged, but the plug was already gone when I bought it. I wonder if it just fell out, or if it was removed intentionally. In any case, here are some pictures of works by the Ichijô Mon for comparison:

-

Good question. It was sold to me as Shibuichi - and that's how it looks to me - but the NBTHK papers say Rogin. I'm not along far enough yet in my studies of Tosogu, and therefore would like to know if there are any telltale signs, or is the distinction arbitrary? Quite frankly, at first I had no idea about what you and Brian talked. I found this tsuba very hard to photograph, especially the Katakiri-bori. I experimented a little with the lighting and angle, and thought that my photos showed the features as clear as possible. However, I now realize that not only the color is off (the patina is actually darker / deeper), but also those S-shaped lines look a little rounded or sculptured, which isn't the case at all. For lack of more objective guinea pigs, I showed the Tsuba to my family and asked what they see. The answer was unisonous: a little stream; that's exactly what I saw all the time. Of course we still can discuss the artistic qualities of the arrangement, but holding the Tsuba in hand it really is obvious that we're not looking at a strange stem but water. Same here, although my limited experience with Kinko probably makes *my* opinion not carrying much weight. While researching the motif on the internet, I luckily found an online seller that sold single pages from the publication KÅetsu (see this post), in which my Tsuba was pictured and described:

-

Barry, what Ted said. In Japan Jabaramaki starts at abut 600.- US $; Bob Hughes should be able to arrange this type of wrap for you.

-

Curran, thanks a lot for your input - I think I now can rule out the Noriaki listed, since the Iwata school worked in iron, even copying the "old masters". This Noriaki is purely Kinko, probably associated to Shonai Ikkin. I got some more material and will write up on it, but for now just some quick pictures:

-

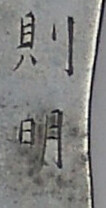

Wakayama and Haynes list a "Noriaki", but it doesn't seem to be the guy I'm looking for; in any case, I'm looking for Mei samples to possibly exclude the one mentioned above. Here's "my" Mei:

-

The characters are taken out of context; they basically only mean "cut in the edge". The description even goes on to explain that the chips in the edge are not due to forging flaws, and that swords with Hakobore can receive Jûyô papers:ã¾ãŸã€åˆƒã“ã¼ã‚Œã¯åˆƒåˆ‡ã‚Œã€é›ãˆå‚·ãªã©ã®ä»–ã®æ¬ 点異ãªã‚Šã€åˆ€å·¥ã®æŠ€é‡ã«ã‚ˆã‚Šç”Ÿã˜ãŸã‚‚ã®ã§ã¯ãªã„ãŸã‚ã€å¤æ¥ã‚ˆã‚Šå—ã‘å‚·ã¨åŒæ§˜å¤§ç›®ã«è¦‹ã‚‰ã‚Œã€åˆƒã“ã¼ã‚Œã®ã‚ã‚‹ã‚‚ã®ãŒé‡è¦åˆ€å‰£ã«æŒ‡å®šã•ã‚Œã¦ã„る例ã¯å°‘ãªãã‚ã‚Šã¾ã›ã‚“。