-

Posts

3,242 -

Joined

-

Days Won

99

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Guido

-

Gassan Exhibition

Guido posted a topic in Sword Shows, Events, Community News and Legislation Issues

Today I went to a sales exhibition at the Nihombashi Takashimaya department store of works by Gassan Sadatoshi, and his son Sadanobu, by invitation of Inami Kenichi. I’m not a collector of contemporary swords, but wanted to have a look at their take at Sō-den, my main field of interest. Although the Gassan smiths are famous for their swords with ayasugi-hada, they also excel at the Sōshū style, and some very fine examples were on display / for sale. As a collector of antique swords, I sometimes feel a twinge of jealousy when looking at those absolutely flawless, healthy blades, exactly like the smith intended them. OTOH, they are also kind of “sterile” (for lack of a better expression, and not meant derogatory at all); in any case, art is art, no matter if it was made in the Heian period, or last week. It’s always a pleasure to meet Gassan-sensei, who is very friendly and humble (and constantly in need of a good haircut 😝). The only downside was the lighting, which was a little bright, so I had to twist my neck constantly to get a look at the details in the blades; that’s also the reason why I didn’t take more photos.- 13 replies

-

- 17

-

-

-

Some people really need to get out of their armchairs, and look at actual swords … First of all, it’s sumigane: 墨鉄 “ink steel”, also called namazu-hada 鯰肌, lit. “catfish skin”. Both terms aptly describe darkish areas of jigane that stand out; the keyword here is “jigane”, not shingane / shintetsu 心鉄, “core steel.” As already pointed out, sumigane is a major kantei point of Aoe swords, along with dan-utsuri. Jizukare 地疲れ, “tired ji“, are dark, rough spots consisting of exposed shingane, usually due to overpolishing. Areas of jizukare don’t show any jihada. Once you’ve seen sumigane and jizukare in person, there’s no confusing the both. The photos – and probably the state of polish – of the sword in question make it very difficult to see if it has jizukare or not; what I see, however, are numerous kitae-ware. Pictures of the nakago would be helpful, but my impression is that we’re looking at a shin-shintō. The nice sugata (insider joke alert!) can’t make up for the poor workmanship, and (from what I see) cobbled together koshirae. I don’t consider it collectable, but even if someone just wants to own a Japanese sword – any Japanese sword – the price is way too high. FWIW.

-

The jūtōhō (short for jūhō-tōken-rui-shoji-tōtori-shimari-hō 銃砲刀剣類所持等取締法) only states in article 18-2 that a person who wants to produce swords has to apply for a permit in accordance with the bijutsu tōken-rui seisaku shōnin kisoku 美術刀剣類製作承認規則, the “art sword production approval rules”. In the application, the smith has to declare the type and number of swords to be manufactured, including the number of “shadow swords”. I couldn’t find any limits mentioned, but maybe there are “guidelines” that are not on public record, as Steve suggested, and/or the smiths exercise anticipatory obedience ...

-

Tanto What do I have here?

Guido replied to Guns Knives and Swords's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

Well, I always considered him an artist, but what do I know? But even mere artisans should be able to offer some insights into the construction of sword fittings, especially if that's what they do for a living. I'm no artist, artisan, nor do I have decades of experience in engineering - but I handled quite a few koshirae the last 40+ years, and some aikuchi were among them. Only those with horn fittings were made of solid material. All other (metal) koiguchi and fuchi were constructed like regular fuchigashira, i.e. with walls of even thickness. Filing them back would therefore result in holes; hammering them back would completely deform the fitting due to the tenjōgane. Deducting from some scratches that it's a cobbled together koshirae with altered fittings is astoundingly brilliant. Or not. "Does your horse smoke?" "No, why?" "Well, I guess then your barn's on fire." Back into hiatus ... -

Well, Chris, maybe my reply was a bit harsher than I intended, but quite frankly, not by much; I was (and still am) irritated by some of the posts in this thread. By saying "basic research" I meant of course exactly that, i.e. basic: looking at the papers, and looking up the smith. You wrote This smith isn’t only listed in the "bible" of sword collectors, the nihontō meikan, but also in Hawley’s and Sesko’s (I’m sure in other standard books as well). Saying you couldn’t find records of this particular swordsmith makes me wonder where exactly you looked. Btw, the sword Chris (Vajo) posted is signed by the same smith, and a few more by him can be found online, although not in the same tsukurikomi. And yes, the seller "claims" it’s Edo period work - for a good reason, because the papers say so, even giving an exact time frame. As for not having a yokote: I’ve never seen a hirazukuri/katakiriba combination blade in my 40 years of collecting that had a yokote; probably because there is no such thing. The way your post was phrased seems to have the purpose of casting unwarranted doubt on the sword being legit; either that, or written without covering the aforementioned basics, to make my point again. And then of course we have that bewildering post by Ken, who says his mentor judges it as modern, and the papers are therefore invalid; even that papers by the NBTHK are generally not reliable. Is that the same mentor who bought a mass-produced, cast, Jingo-esque iaitō-tsuba, and judged it as textbook Yagyū? I just hope his "elite" Sōshū sword collection was purchased with a sounder judgment than occasionally shown here … Well, I’m obviously guilty of , so I think I now should take a break from the NMB, and go back to eating $ 100.- sushi, and looking at my five figure swords.

- 38 replies

-

- 12

-

-

The smith is listed in the meikan (page 863), and there are no “daimyō papers”, just a photo of the registration. And katakiriba swords usually don’t have a yokote. I don’t know the seller, I don’t endorse the sale, I don’t like the horimono - I just find all this shooting from the hip and NBTHK bashing - instead of doing some basic research - kind of annoying.

- 38 replies

-

- 11

-

-

Did he actually read the paper, or simply dismiss it?

-

Isn’t that the guy who registered “Nihonto” as a trademark, and threatened the NMB with a lawsuit if that word wasn’t removed from the forum?

-

Request for Identification Assistance

Guido replied to EckartF's topic in General Nihonto Related Discussion

The only reason it might not paper is because the shinsa team is laughing so hard at the kinpun-mei that nobody is able to use their writing implements. Seriously, though, the lacquered mei looks pretty fresh and like acrylic paint, and should come off with careful use of solvents. I usually don’t promote messing with swords, but can’t see how it would do any harm to the patina (been there, done that, got it straight from the horse’s mouth). At least that‘s I would do, because it’s kind of embarrassing to have a “to kinpun mei ga aru” on my papers “attributing” it to one of the most famous sword in Japanese history, and a national treasure, no less! -

Monkeys are most often portrayed in Japanese art with peaches, persimmons, loquats, or chestnuts. Since the fruit cluster in this case doesn’t resemble any of them close enough to be 100% sure, I went with the leaves as the determining factor, giving the fruits some artistic license. As Sherlock Holmes said: “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” And since I mentioned Mr. Holmes: our resident Dr. Watson sent me a link to the original sales listing, where the hozon papers are shown that say it’s chestnuts. I don’t want to hand anyone a can opener to let slip the worms of NBTHK-bashing, but I’ve seen quite a few tōsōgu papers where they got the motif wrong, as they certainly did with this kōgai. They probably just took one of the above four fallback fruits since they, too, couldn’t come up with something more convincing. So, am I sure those are loquats? No. Do I still keep the bunny/pancake picture on my hard drive? Hell yes!

-

Not the price difference, just the price of the first tsuba is ludicrous, and that has nothing to do with papers. Other than that, Ken and Guyan hit the nail on the hat.

-

Monkeys and loquats, a very common theme in China and Japan.

-

Maybe 三峰 Mitsumine.

-

廣 is the old form of writing 広, so the family name is Hiroi 廣井.

-

Basically yes

-

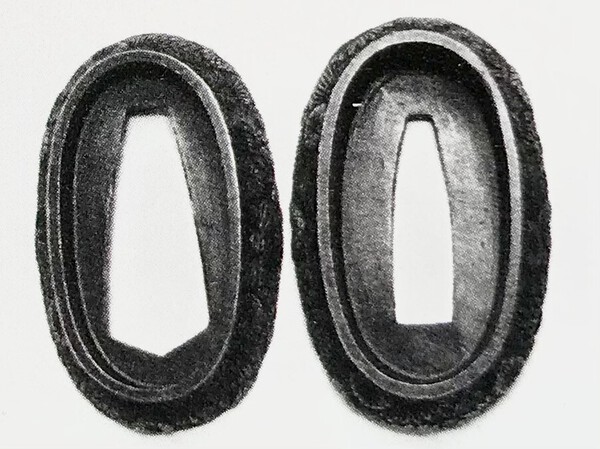

両櫃孔 ryōhitsuana, hitsuana on both sides

-

伊賀守金道 Iga (no) Kami Kinmichi + length (2 shaku 3 (?) sun 6 bu) 山之内家伝来 Yamanouchi-ke denrai (heirloom of the Yamanouchi family)

-

Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai

Guido replied to Bazza's topic in Other Japanese Arts

I don‘t - still mourning the loss of time that was the result of watching that movie after its release. Not art, and definitely not Japanese. What‘s next? A 4K restoration of “Blue Lagoon”? Can’t wait ... -

The color reserved for the Chinese Emperor was yellow, not red - but I think they made an exception in this case to set it apart from the lesser swords made for the Son of Heaven. It’s obvious that this most breathtakingly beautiful sword was made with secret techniques; the smith - spirited away from Japan - was probably killed after making it, his body buried under the Great Wall to prevent that another supreme sword like it was ever made. If one looks closely, the forging pattern reveals the cleromancy from the I Ching - there is no other sword like it! Are we done now?

- 27 replies

-

- 10

-

-

Can’t find the thread, but those were discussed on the NMB before. I bought one in Japan directly from the maker, and found the quality rather low, the worst being the cheap cloth they glued unevenly into the compartments, and that is way too rough for tsuba, especially soft metal ones.

-

As I said above, the terms shouldn’t be taken literally. Besides, they have been established by now, and I don’t expect any changes among sword collectors/dealers/curators and so on. Don’t overthink things.

-

I think the answer lies in the term gendaitō = “present day sword(s)”, i.e. at the turn of the century, when this term was coined. Some time after the war, when sword making resumed, there was a need to give those swords a description without re-writing all books on swords, so the shinsakutō = “newly made sword(s)” was “invented”. My guess is that those terms will remain for the forseeable future, and shouldn’t be taken literally - after all, if a sword is made today, it’s a shintō = “new sword”, isn’t it?