-

Posts

193 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Everything posted by BMarkhasin

-

Junichi, The second question you had was regarding metallurgy. I will not engage in further dust-ups with Ford on this topic, so take what I post below as uninterpreted fact. Again, refer to the 2008 article for a perhaps premature interpretation, but I think one that still likely contains some good ideas perhaps in need of adjustment. Some literary sources have noted that the use of shibuichi in Kamakura – mid-Muromachi tosogu. Heckmann described an SEM analysis on an Ezo menuki as shibuichi. I have tested numerous examples, with all but one (the kogai pictured on page 2 of the thread), testing as essentially shibuichi. Below is are examples (raw data summary) of the base metals of the Muromachi tiger menuki and the Nambokucho Akebi menuki, both on page 2 of this thread. Note that in all my tests, a common procedure was used, where a surface test was taken, a tiny (microscopic) scratch was made and tested to get past the surface gunk/patina, and a test was made in a window within the gilding at the intersection of the substrate (base metal) and the gilded metal. This provided a thorough range of results for each piece. Also, multiple points were taken on each piece, so for instance, 7 spots were tested on the Akebi for base metal, and 2 in gilding windows. You need to look at the Wt% (weight %) column for the compositional breakdown - this is tied to the elemental display below. While this is indicative of other results, there is range of composition on the Cu (Copper)/Ag (silver) spectrum – its not uniformely ~75% copper, 25% silver. Call it shibuichi, a species of shibuichi or the shibuichi family - whatever, its essentially shibuichi. Minor amounts of elements such as gold are occasionally observed (as in the Akebi example - Au=gold). Gilding tests indicate not-insignificant amounts of Hg (mercury) in some examples. Other metals are used on these pieces, and koshirae, including tin, gold and silver. The kozuka I illustrated tested with the central field being silver, gilded with gold, while the housing a shibuichi. Yamagane must also have been used, but again, it is I think relevant that only one example I tested was gilded yamagane. The above is based on real SEM data, no interpretation, and should be treated as factual evidence. I am not going to debate production methodology, as this is not in my range of expertise or necessarily interest, but in my opinion, there is a gap in understanding which needs to be assessed. My early mistake (perhaps) was that in 2008 I tried to address a complex issue, too early in the game. The speculations were rooted in observance, and musings of the technical people, but required additional pursuit. Unfortunately, I was told that to really understand the metal, I would have to conduct destructive tests. I was not prepared at that time to sacrifice any pieces. However, I now have several early bits which are badly damaged, and candidates for such testing. This is a future project. When you begin scanning literature, if a base metal is mentioned in connection with Ezo, it will usually be yamagane. I believe this is a common mistake, and the fall-back metal for pre-Muromachi tosogu. Essentially if its pre-Goto, clearly not bronze, it is by default labeled Yamagane. To my knowledge, there have been no efforts (published) to test metallurgy even among the Kokuho examples. This is an unfortunate truth, and contributes to the misunderstanding of this group of fittings. This perception is now beginning to change among private collectors, and I hope will eventually infiltrate the museums and jinjas. As an anecdote, the TNM once displayed and published a piece in my collection as iron, when it was clearly a black-lacquered soft metal. It’s a lot easier to mistake shibuichi for yamagane and vs. I hope this helps further clarify things. I think now, most topics of relevance pertaining to Ezo have been covered in this thread (among the annoying dust-ups - sorry for my part). As I mentioned earlier, I will avoid engaging in speculation and interpretation of the metallurgy until I can engage a qualified professional to review the data in context with the physical pieces, and possibly add the destructive testing. I will be offline more often than not for the next several weeks. I can only imagine what wonderous threads I will find waiting for me when I return, and the joy it will bring me! I personally would like to learn something about Ko Mino works – as the second part in Junichi’s initial posting. Best, Boris.

-

Junichi, I will attempt to get back on the intended track and avoid future pointless dust-ups. You had two questions in your last post. Let me answer each as best I as I can. I will post 2 replies. First is the question of how/why we call the early examples of disarticulated menuki as Ezo? Here, admittedly we face a problem. There are to my knowledge no extant (published) Ezo style uchigatana or koshigatana from this early period to use large menuki. This was a turbulent period and understandably the record is sketchy. The term Ezo is applied most to Muromachi period fittings. This designation is extended back in time to include disarticulated kodogu and koshirae which resemble the Muromachi examples but are considered older. We are in essence tracing back a possible lineage based on more modern examples. There are no set guidelines, and designation is based on analogy of style, while age is ascribed based on analogy to items with more established chronologies like armor, as well as a sense of relative position based on artistic attributes. Clearly there is room for debate, but there is a general consensus. I have taken liberty of summarizing some kantei points to consider. Kantei points for the early disarticulated examples (Kamakura/Nambokucho): 1. The best examples have a relatively heavy-walled construction and an ‘ordered’ proportional appearance, often in a lozenge shape 2. Floral motifs are most common, although shishi’s and other critters with mythologic attributes are possible 3. Numerous unique sukashi elements (often with irregular edges), with sets never being mirror images; 4. Larger size is common, but not a necessity (see tachi koshirae with series of small tsuka-ai); 5. Often with significant depth, with ‘tiered’ levels –ie. central elements such as peonies will stand above the underlying karakusa vines/leaves to even heights 6. Central elements may be in sets of 3 or 5 (ie. like early mitsu-mon or go-mon kogai/kozuka) 7. Backs may or may not have posts 8. Gilding is relatively thin and extensive, with worn areas from use, not as in later Muromachi examples by mimicking ko-kinko/Goto techniques. 9. Koshirae are rare and varied. Kairagi-zame (coarse same) on the saya is common, tsuka is typically banded in metal, but can be exotic hardwood. Metal banding with high amounts of sukashi, often resembling armor is recognized. Banding can be backed by gilded metal, or placed over black lacquered wood. Metal banding from koiguchi to past the kurigata or kaeritsuno is common, and many are of nomiguchi style. Often with a high profile and narrow oval cross-section. Inlayed saya (mother of pearl) are known, not dissimilar to some tachi of the time. Kojiri varies from narrow to more cap-like, and there may or may not be a kashira, leaving the butt of the tsuka exposed. Koshigatana predominate but tachi are known. Kantei points for disarticulated Muromachi examples: 1. Best examples retain the traditional heavy walled construction, but many are thinning 2. Resemblance with ko-Mino – more dynamic florals, insects, critters of all types 3. Sukashi is common, but subgroups appear with virtually no sukashi (may not be intended as tosogu originally) 4. Designs are less tiered, more fluid / organic, with nearly 3-D representations possible (see kirin/dragon examples on page 2) 5. Gilding is still relatively thin, but starts to resemble period kokinko kogai, looking purposely removed in areas 6. Shibuichi is most common, but yamagane begins to increase to end of the period 7. Koshirae can utilize large amounts of kairagi-zame, banding from koiguchi to past the kurigata or kaeritsuno and on the tsuka is common. Many koshirae accommodate both kozuka and kogai. Fully metal examples are known, and some continue in nomiguchi style. Sukashi banding is backed with gilded metal or over lacquered wood. Exotic woods for the tsuka can be used, as well as mineral/stones/glass. Kojiri tend to be large, extending up the saya like on tachi of the period. Koshigatana predominate but tachi are known, and cross-section can be high narrow oval to more standard Muromachi forms. Kantei for later examples / revivals 1. Virtually any subject is possible, from insects to people, boats, various animals, plums and sakura are common as single blossoms on a twig 2. Fuchi kashira / kojiri in proper Momoyama/Edo style are common 3. Gilding starts to look forced, with areas clearly being removed for effect 4. Height and depth of execution is lost, with designs being very low relief 5. Usually have retention pegs on the backs 6. Generally smaller size (standard Edo sizes) 7. Shibuichi is common in the early period, but is quickly supplanted by copper 8. Full koshirae are encountered from the Momoyama/Keicho and are generally shorter koshigatana, trending to tanto. Typical Edo cross-sections. Not to be confused with rustic northern examples attributed to Ainu (shown elsewhere in this thread). Hope this helps frame the styles. Variations exist beyond what is listed above, and as always, common sense prevails. Best Regards, Boris.

-

Ford, In 2008, we had only hard results, and not yet the time to fully make sense of them. The ideas presented on metallurgy were only a segment of the article, and represented early musings of the engineers / metallurgists who were involved in the testing. The results clearly indicate metal to be shibuichi. This is exactly why above I said that I prefer to wait for professional guidance (engineers, metallurgists) before future publication on the topic. I am certain I will look back and say some earlier thoughts were unsophisticated and need either modification or perhaps even negation based on new data or a comprehensive interpretation. I prefer to let the professionals take lead in metallurgical interpretation of the analyses. I wont deny that some of your comments may have merit, but beyond standing behind the raw data and dating of these pieces, I will refrain from senslessly opining. I will stay rivetted to the computer to hear your interpretation as a craftsman, despite not having access to the SEM raw data and the pieces themselves. I hope you have the courtesy to start a new thread, so this one can attempt to stay on topic in regards to the tosogu. Best, Boris

-

Ford, Not saying that time-frame is tied to metallurgy at all - shibuichi has been known in Japan from the earliest times, and is not exclusively an Edo product. The pieces I have tested are largely shibuichi. They are defined in the context of numerous other examples and literature into a general and supportable chronology. If you disagree with that chronology, well..... there is probably no cure. To suggest that the pieces I have shown are Edo suggests a pedestrian understanding of pre-Edo fittings, and disregard for literature. Myopic philosophizing. Sorry (moderators) to sound harsh. Best, Boris.

-

Gentlemen, A lot going on in this thread at this point, so I concur with Junichi about a possible separation into a couple of related threads. Ford, I have a lot of metallurgical raw data and photo-micrographs at this point on a wide range of Ezo, Ko kinko, ko Mino pieces, old Heian tachi bits, as well as 'calibration' runs on archaic chinese bronzes - I have tested virtually every piece that has gone through my collection since 2006. I am not prepared to open the kimono and release all raw data because it represents a large personal financial and time investment. At some point, I still hope to be able to publish the results in an organized manner, hopefully with professional guidance and in a journal. However, in the interest of sharing relevant data and education, I will post an example of one SEM/EDS test result on an early piece of tosogu in the coming days which shows the metal is a shibuichi. As for the contention that the old Ezo pieces are actually Edo??? I'm not going to bother even going down that path. Any contention that shibuichi is somehow fixed to a later time is incorrect. The use of shibuichi (compositional attribution) is documented outside of Japan, and from significantly earlier examples. It is also documented by SEM analysis used in lacquer from Shosoin collection items dating to the 8th c.. As a craftsman, I leave speculation on production techniques to you. I'm interested in the historical context of the tosogu, not so much the mechanics of production. But again, I point to the notion that to opine on production, you need to have had the pieces in hand and have studied them. It is possible/likely that since Ezo represents a large time-span and geography, production techniques varied. Best, Boris.

-

Hi Tom, Thanks for posting those excerpts. I had forgotten where I had seen them. Below are pictured some "Ainu" style Ezo koshirae. I will try to get a better scan of the tachi style without tsukaito, and I have a few good images of the silvered type, fully banded in metal. These as you can see are dramatically different workmanship to the old, classic style of Ezo koshirae that are attributed Kamakura through Muromachi dates. The idea is that after the trade and armament restrictions on Ainu populations were imposed by the bakufu (Matsumae clan was charged with enforcement / regulation), functionally the development of northern armaments stalled, and the north became a time-capsule of sorts for this old style of koshirae. The Ainu kept creating weapons in koshirae which resembled the old traditional style, but their iron working and soft metals skills were inferior. It is generally agreed today that all such works are a local northern-most Honshu/Hokkaido products. You can still buy them today, although not cheaply. In terms of metal varieties, the banding on the koshirae range from pure silver, to yamagane and brass. Tin is also used, and gilding is fairly common. The Japanese consider such pieces as little more than mingei... which is too bad, as they are an important end-point in koshirae evolution. Dates are hard to ascribe with any certainty, and they span from Momoyama to Meiji depending on who you ask. In a few pieces I have seen, there seems a blending of old bits like tsuba which seem traditionally made early Edo period items, coupled with these more rudimentary koshirae. The Umetada revival pieces have been brought-up earlier, and a couple of examples of tosogu posted, as well as a reference to a particularly good and well-known tanto koshirae of Momoyama vintage (there are others if you scan the literature). I believe however that the dates attributed to the Umetada revival are a bit earlier, dating from the Momoyama/Keicho. Those dragon menuki came with a Sasano hako gaki as gold gilded shibuichi to Umetada of early Edo if I recall. I have even seen early Edo shippo koshirae in the old Ezo style. Again, I think this is a testament to their importance and favour historically. Again, it goes to show you how bad this title of "Ezo" is, and how broadly its used. We need finer, more pertinent tosogu terminology defined for this group, but it doesnt look like that will happen any time soon. Best Regards, Boris.

-

Henry, that is a great book, and likely the most informative in my list relating directly to what was happening in the Kitakami Basin. I have re-read it several times, and find it useful on many levels. Check out some other titles by this author. Note my edit in the last comment, and again, I say with respect but sense of reality... Best, Boris.

-

Henry, Junichi, et al, Here is a rough list of references I have found useful in the past. This is rushed, and I am not getting into specific articles in the journals -- your interests will guide you. The book list contains many currently available titles, and in these, you will source others of interest to you. I have avoided listing foreign sources, private publications etc... This should be sufficient to get you started. This is not in any particular order of importance. EDIT: The books below are for the large part non-nihonto because the usual library we rely-on is largely useless outside of providing photos. You have to know what the photos are telling you, and how they fit into the broader picture. If you try to scour the titles below for any of the concepts I have outlined, you wont find them. These titles will provide a back-drop for further independent study. Henry, I understand you want to convince yourself one way or another, but you wont do it through this thread. It will take you years of study, as it has done for me. A forum is a place where ideas are shared - not a place for a free higher education. I have done about as much as I can to outline the ideas and point people in a direction. Its taken me years, and a lot of sheckles to get here. You can decide you are genuinely interested in this topic and commit to its serious study, and build, change, negate what I have outlined. Or, you can mope around, kicking dirt and complaining that I am not spoon feeding every detail of every one of your cascade of questions and doubts. I don't intend to be harsh or disingenuous, but this is not my job, and this is not the place. This is not an easy area of study, information is sparse, and it requires independent thought, a broad background knowledge base, and exposure. As I said, and I can't get any clearer on this -- if you are not willing to ante-up, you may as well forget it and move on... PS - I'm not nearly so narcissistic that I require a mutual appreciation society. However there are people out there who grasp the above concept (and the potential futility of what I am doing here and now), and prefer a modern ride to a Model T. Books The Culture of Civil War in Kyoto, M.E. Berry. 1997 Heian Japan, Centers And Peripheries, M. Adolphson, 2007 The Gates of Power: Monks, Courtiers, and Warriors in Premodern Japan, M. Adolphson, 2000 State of War: The Violent Order of Fourteenth-Century Japan, T. Conlan, 2004 Across the Perilous Sea: Japanese Trade with China and Korea from the Seventh to the Sixteenth Centuries (Cornell East Asia), C vVerschuer. 2006 Studies in Asian Geneology, Palmer, Brigham Young University, 1972 Ancient Populations of Siberia and its Cultures, A.P. Okladnikov, 1959 Northeast Asia in Prehistory, C. Chard, 1974 An Early Style of Japanese Sword: A Search for the Origins of the Curve, Sano Art Museum, 2003 Hiraizumi: Buddhist Art and Regional Politics in Twelfth-Century Japan, M.H, Yiengpruksawan, 1998 Tosogu no Kigen, M. Sasano 1979 Nihon no Bijutsu 332, N. Ogasawara, 1994 Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues on the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan, W. Farris, 1998 The Japanese Sword: Iron Craftsmanship and the Warrior Spirit, TNM. 1997 Tokubetsu Ten: Kinko Mino Bori, Gifu City Museum, 1993 Warabite-To. M. Ishii, 1966 Oyamazumi / Kasuga / Tanzan / Itsukushima / Chusonji Jinja Collections, various Ban Dainagon Ekotoba details Heiji Monogatari Emaki details Journals / Articles Journal of East Asian Archaeology, various Monumenta Nipponica, various Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, various Artibus Asiae, various Ars Orientais, various Geological Survey of Japan, various Techniques of the Japanese Tsuba-Maker. E. Savage & C.S.Smith, Ars Orientalis, Vol. 11, 1979

-

It would have been nice if art historians would have applied attention to Ezo tosogu, but that did not happen. Rather than reinvent the wheel, the first thing I did when I began researching, was inquire in Japan on whether anyone had pursued this topic. Unfortunately, the answer was 'largely no'. Sasano began to look at Ezo koshirae as evidence to frame his ideas on uchigatana development, and idea that certain groups of tosogu were often older than conventional art-historians were thinking. When you look at the Heian / Kamakura period Emaki (horizontal scrolls), you see blade-edge up swords being utilized. Often, these are without tsuba, broad, not particularly long, and ornamented with bands / rings. They resemble Ezo koshigatana. This is a whole other topic to pursue perhaps in the Nihonto section of the board. Best, Boris.

-

Gents, Thanks again for the positive comments and participation in the discussion. We have advanced the Ezo discussion enough I think to give everyone a pretty good flavor of the pieces and issues surrounding the group. What about the second part of Junichi's question - Ko Mino? We have had several items posted, but nobody has taken the lead in that discussion. I know there are a few advanced collectors of ko Mino out there, so can anyone take this lead? Looking forward to a healthy continuation. Best, Boris.

-

Jean, Thanks for the kind words. I am transferring the site to Andy Mancabelli, but he has been very busy in Japan lately and the timeline has kept slipping. I hope he will have it running sometime in the spring. I imagine that a notifier will be sent in advance of the restart. Best, Boris.

-

Thanks John, Extraterritorial influence exists all over NE Japan, and it is clearly documented that contact existed into the early Heian with known continental areas, and other named, but unidentified areas. However, so few pieces of tosogu exist from this period, from the north, it is impossible to show a clear influence. There is a lot of period material preserved in the Kinai, probably due to preferred trade and governmental mission routes. This is also why my theory suffers for evidence in the early phase. There are a couple of warabite koshirae preserved from the 8th/9th c, which show scroll work chased on metal bands encasing the saya, but it is fairly non-descript. Different from the examples you posted on kara-tachi (not so fine, or extravagant), and more like Kofun works. Then there is a frustrating gap (which suggests a re-evaluation is required), and we have the koshigatana attributed late Heian dates and termed 'Ezo', as well as late Heian attributed Kenukigata tachi, which have some ornament (also fairly non-descript). I have an idea for an indirect path of evidence which I am pursuing now, but its too early to comment. Best, Boris.

-

Sad to come back to a thread after a couple of days to find it has been diluted with a bunch of crap posts. Philosophizing with a hammer... The Rosin book examples are lovely, and while I have not handled them directly, some of them (page 127) look a lot like a couple of examples I posted which have little or no sukashi, and could have been used on items other than koshirae, such as ornamental box fittings. The TNM has a great example on display (I visited in November 2013), dating to the Muromachi (15th c.), with a number of very similar pieces affixed to an urushi writing/paper box. In particular, the phoenix on page 127 seems incongruous as a piece of tosogu due to its vertical orientation, but that is not to say it could not have been used as saya kanagu. In particular, the tsuba is very interesting. I have seen only one other of this type. Discussion of Ezo works is encumbered by the term “Ezo”, and shoe-horning these works into a concept of a school. Both of these aspects are unsupportable and ideally should be dropped. The designation of ‘Ezo’ is a terrible misnomer since it equates a group of fittings with regional, cultural and chronologic implications. Emishi should not be used to describe these fittings for similar reasons. The implied idea of an Ezo school is unsupportable, since as I mentioned, ‘Ezo’ works span hundreds of years, and a large geography. These works encompass numerous manufacturing centers, but there is no evidence of a production associated with a non-Japanese ethnic group, that is to say they are not Emishi/Ainu products. These were made in all times, in all areas by Japanese craftsmen. Unfortunately, the term 'Ezo' is used by all collectors and shinsa organizations, and as such is not likely to go away any time soon. For better or worse, I have framed my discussion using this term. While I like Sho Ki-Kinko, or first period kinko, it also suffers from being too vague. You could use it from late Yayoi, and when do you stop using it? This term is not new to Japan, it has been proposed, but never caught on. Guido’s suggestion of Joko Kinko is interesting, but will run into similar problems. The question of terminology has a ways to go. As to metallurgy, if you doubt that the majority of earlier pieces are shibuchi, all I can do is suggest hitting the books. In the 2008 KTK article, I discussed results from SEM EDS analysis of a number of pieces spanning Kamakura to Keicho. The analysis was conducted in the University of Calgary, under direction of the Engineering faculty’s Material Science Group. By 2008 a total of over 30 pieces of Ezo, Ko Mino and Ko Kinko were tested. I seem to recall Heckmann mentioned a shibuichi SEM result on a mid-Muromachi piece. Numerous publications have recognized the use of shibuichi, yamagane, silver, tin and gold. Objection has been raised in this thread by my use of the idea of breaking up Ezo into periods, as well as an early northern influence. The assertion is that my comments are unsupportable, or at least difficult to support with available sources. My ideas are based on having collected, and handled numerous individual pieces as well as complete koshirae, and having detailed discourse with their owners. I could claim that early Ezo koshirae have a different shape, construction methodology and a variety of structural and artistic nuances which distinguish them from contemporary non-Ezo koshirae, and I think this may be due to northern association. People could and should insist on an explanation backed by visuals. Unfortunately, this can’t be easily be provided (understandably), since it would involve access not only to the pieces in question, but also to the Ezo comparison group, and predicated on everyone having access to other ‘standard’ period koshirae – which also isn’t going to happen. Not to mention insights from years of review of published and unpublished materials. It comes down to a level of faith, or at least suspension of disbelief, under the premise that I have been thoughtful with the materials, and have nothing to gain by promoting any specific idea. Without ownership or serious directed study, the most that can be aspired to is philosophizing and rehashing. You need to physically handle lots of high-end antiquities on an ongoing basis and discuss them with others in the know. If you want to know about Nobuie, Namban, Goto, armor, koshirae, etc.. talk to collectors (dealers) who have committed to their acquisition and study and ask to handle the pieces directly. When someone like Fred Geyer shares a view on Namban, whether it is easily supportable or not, I take it as meritous based on what I know of his depth of pursuit. I can think of a handful of people who may have handled or owned more than I have of Ezo works, and none participate in this forum. As I said earlier, you can take it, leave it, use it or abuse it. From the PM’s and emails I am receiving, I am glad that many are choosing to use it. For those interested in actually learning something and gaining practical experience, I am always open to sharing my collection pieces and research, including participating in study groups. I've poured a glass of wine, and look forward to the ever-entertaining commentary that is sure to follow. Best, Boris.

-

Ford, I assume you are speaking about yourself. I wont comment. Schools are a relatively recent phenomenon, and I have never suggested Ezo as a school. I certainly don't think it appropriate to call it a school -- or use the term Ezo for that matter, but we are stuck with this crappy terminology and have to dance around it. We are speaking about a broad group of works which spanned hundreds of years and a large geography. I suggested an early northern influence, and early links to Mutsu, Dewa and northern Kanto regions. I personally think the earliest examples originated in the general area around Hiraizumi / Sendai, but in craftsmanship were related to Kinai works. I also think that starting from the Kamakura / Nambokucho, these works take on a more southern flavour and were likely produced largely in the Kinai. Some may not have been originally intended for use as tosogu, and I see the possibility of links to armor and other arts of the period. By mid-Muromachi time, they are supplanted by ko kinko and ko Mino works in popularity and then go through a few revivals. There is a large variety within this group of works, as should be expected. I have also said that as we are dealing with pieces of tosogu that could date back 800+ years, and there is a paucity of examples and research either western of Japanese. I have offered my insights and ideas on the subject, and pointed to one of the very few western articles which people could access. I think that Buttweiler's thoughts have merit, and he should be credited for introducing the subject to western audiences. As for opining on the koshirae I have presented, I have not shown them to suggest a commonality, but as what is now taken as the best representatives of this group of works. As for the term Sho Ki Kinko, I personally have always liked this term, and use it often when speaking about early pieces, rather than Ezo, ko- this and ko- that. I will say that it is critical to handle these pieces and compare them. Images simply don't do them justice and miss all nuance. Take it, leave it, use it or abuse it... Best, Boris.

-

Henry, No problems, and taken in the spirit it was intended. I happen to agree with you, it can seem ad hoc. Some things are only learned through direct exposure/experience and layering-in information picked-up along the way. Occams Razor applies as well I suppose. I'm a pragmatist, and abhor fits of fanciful dreaming, so I hope I am presenting my ideas clinically. The fact of the matter is that if as collectors / researchers of tosogu, if we relied on the published 'gospels', we would be just rehashing ideas of old, and focused on the mainstream interests. I have chosen to invest my time, energy and a lot of capital to pursuing ideas that I have found to be problematic. Ezo is one example. I believe that things like historic, cultural, religious, economic and ethnograhpic context are critical in understanding antiquities, and this is what I have tried to incorporate in my studies - plus some hard science where I can. Expressed above are my ideas based on observation, lots of independent study, collaboration of other collectors / researchers (mainly in Japan), and investment in areas very few others are interested in pursuing. I reserve the right to change those ideas as new or contrary information comes to my attention, and I am certainly not married to any of my ideas. The pieces I have kept in my collection and spent time on, are those which tell a story, and fill-in gaps. My thoughts are not ground-breaking (well ok, I like to think maybe once or twice ), but perhaps instead 'integrated'. Blah blah blah, you get the point. Best, Boris.

-

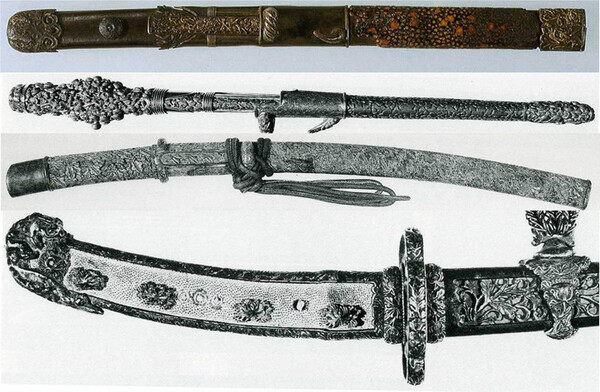

Junichi, Most of the Ezo menuki I posted, as well as the Kamakura/Nambokucho koshirae were made as such, and is thought they do represent early (relatively unmolested) examples (not re-used bits). There is a slight possibility that some of the sukashi-less menuki examples may have been used elsewhere (not tosogu). Note that all koshirae date no earlier than the late 12th c. Even the armors I have illustrated date at the earliest to the latest 12th c. This leaves an obvious problem, in that we lose our articulated examples as a basis of comparison, and assigning Heian dates to ‘Ezo’ works is dangerous. Not to say examples don’t exist, but any interpretation will be subject to doubt. What did northern work look like during the early Heian? I think we need to look to fragmentary Heian armor associated with northern clans, and a few extant kenuki gata tachi and warabite to with preserved koshirae. This is painfully limited dataset however, so again, lots of opportunity for (mis)interpretation. One of the earliest extant koshigatana koshirae is pictured as the top example in the image below. The tsuka pommel cap is of Heian style, and likely this piece dates to ca. 1200. The kojiri however is a later modification. Specifically, the two early menuki I posted are in my opinion definitely made for koshirae. They have a slight curvature intended for mounting on a tsuka or saya, have that lozenge shape and are just the right size. As armor kanamono, their shape and style would not have worked. The koshirae illustrated throughout this thread were designed as such, and not made of recycled armor bits. The images below should leave little doubt that the koshirae use fittings specifically designed for them. However, you must understand that recycling was not in any way a negative thing, and during these early periods, it was normal and acceptable practice. Consider the environment, the relative lack of resources and available manpower, no mass production, and you start to appreciate that people had to make due, and parts transfer / mending was part of life. The same artist who worked on your koshirae may well have worked on your armor, and your statuary. Now as clarification, this is not to say that the koshirae were not later tampered with. For instance, a kojiri may have been lost or damaged, and later replaced with an obviously diachronous and slightly mismatched replacement. This is also common, and should not necessarily be viewed as diminishing quality or importance of these koshirae. If anything, it’s a testament to their importance that owners would have employed kanagushi to restore the pieces - many were luxury goods at the time of manufacture. Most of these types of koshirae (and their blades), are registered as Important Cultural Properties, and a few are Kokuho. In the image below, of one of the most recognized tachi koshirae of 'Ezo' style, its obvious that the ornamentation differs between the tsuka and saya. In this particular example, the pommel cap is also a replacement. So throughout its life (oldest bits estimated at early to mid-Muromachi), it had undergone multiple historic restorations, with the view to keeping the style consistent. Below is an image of an early koshirae, with what appears to be a platform drilled with a hole, which looks a lot like those we normally associate with armor kanamono for the placement of byou (fasteners). Also just because I referenced a yoroi earlier in this thread, it is not to suggest that only they could have shared styles with Ezo tosogu – also haramaki and dou maru etc.. Kozuka Kogai from this period are virtually non-existent, and many are of rough or archaeologic condition. Most are simple, very thin (<2.5mm), varied in size (length and width), and vary in style, with some having a reverse mimi (saka mimi), some no mimi at all. Blade styles vary as well, from inserts, to integrated examples like umabari. They are typically yamagane and gilded or tinned, although bronze, silver and shibuichi were used. There is a large variance in kozuka/kogai associated with Ezo koshirae, and I am personally unsure if I would call many of them ‘Ezo’. Just goes to show that variance is a characteristic of early period works. None of the kozuka kogai I have seen incorporate ex-armor kanamono. PS - note the silvery gold colour of the Ezo kanagu in the image above. That should give you some idea of what people refer to as the silvery sheen seen on older pieces... Its not exactly right colour vs real life, but its getting there. Best, Boris.

-

Junichi, Good questions... let me put some thought into the response and compile some visuals... Your question, focused on the early period materials, makes the use of visuals tough since there is a paucity of materials, and hard conclusions are dangerous. Best, Boris.

-

Gents, That was fun, but seriously speaking now, the question of what influenced who, when, while looking back through the haze of >1 millenium as laymen is too arduous to begin to address in a thread intended for Ezo and Ko Mino tosogu. I see this thread immediately and irreparably going on a tangent. If we are to opine on esoterics of artistic influence in remote corners of 11th century Japan, I think a new thread and fresh bottle of wine are warranted. There is actually fairly exhaustive literature, (in some cases, rich in speculations) on the subject of finding northern influence overprinted on Heian Kinai aesthetic - from temple architecture to buddhist sculpture, to religious beliefs, etc. When cultures collide, the dominant one directs, the minor ones overprint. Finding northern influence on Kinai artistry is a subtle proposition, but there is literature out there. There is considerably less direct evidence, but lots of circumstantial evidence of extraterritorial influence in northern Japan, and again, there is literature on the subject. If NMB members are interested (and when time permits), I can compile a list of articles/books on these subjects, and provide a guaranteed cure for insomnia. If someone wants to talk about tosogu, lets do it, but waxing lyrical on speculation and esoterics is tiring and unproductive. Best, Boris

-

Its an old photo, but ya, I still got the goods!

-

Henry, LOL. You crack me up.. 1 Mill. BC is first millenium BC, not Flintstones! On the other remotely possible connections... if you look hard enough, you will usually find what you are looking for. Best to focus on Ezo within the scope of tosogu... my ¥2. Sorry, but I just cant resist.... Best, B

-

Junichi, Regarding the silvery/grey colour of early pieces, thats tough to get across without handling. I have never been able to successfully photograph Ezo pieces to show the subtleties. The backs of Ezo pieces also are highly varied, some with posts, others without. I think this reflects versatility and variance of use... again hard to pin-down with definition. Regarding armor connections, look to the Heian/Kamakura examples in Kasuga jinja (with the wonderful metalwork on the o-sode and kabuto). In the KTK article I also showed a Nambokucho Ezo koshigatana koshirae with a flat spot on one of the sukashi bands on the tsuka or saya, drilled-through for an apparent Byou. I think that was a great example of how these sukashi pieces could be used interchangeably between armor and tosogu. Note the similarity of style of the peonies, the scroll work on the armor kanamono to the Kamakura/Nambokucho Ezo fittings and koshigatana koshirae I posted earlier in this thread. Best, Boris.

-

Gents, I like all the interesting ideas, and that people are thinking about the artwork in a broader sense, but I agree with Junichi that we have to show some restraint in over-comparing. Henry, in your comparisons, you were comparing Scythian (1 Mill.BC), with Tang/Nara 8th c AD, with Nambokucho (14th c.) and Muromachi ca. 1500. I think this type of comparison creates red herrings (ie. Shang dynasty Tao Tieh masks vs Canadian West Coast Indian masks). I would argue that there are only so many ways to faithfully represent scrolling vines in a limited space on a decorative metal fittings of any type, and so it is totally natural that there would be obvious and easy points of artistic comparison without any tangible direct influence. I could, for the sake of argument and 'devil advocacy' suggest that similarity exists in Japanese representation of river reeds with those of middle-Kingdom Egypt... its an insane suggestion, but artistically, there are likely to be points of unity. In my opinion, comparing Shosoin examples (Asuka to Nara period 6th to 8th c.) to Ezo works is of limited value, despite the Japanese connection. There is clear, documented foreign influence in Shosoin and Horyuji treasures, since many of the items were actually tributary / trade goods imported directly from China, Korea, Parhae and other regional powers. I dont doubt in the same period, that northern trade goods would have showed similar influences, BUT, the percentage of extant Ezo works from this period is so infinitesimally small, it would literally have to be one in a million, and then likely only remaining in Jinja collections, and very very hard to date with confidence. Lets not lose sight that although very rare, the overwhelming majority of Ezo works we have today date no earlier than late Heian/Kamakura. By that time, arguably we would only have been seeing vestiges of original continental influences that may (or may not) have infused Emishi works from Asuka to early Heian. Most Ezo pieces we have were produced in the Kinai (Kyoto/Nara), within the framework of earlier 'northern' styles. If minute points of similarity exist with Persian etc.. it would have been virtually accidental, by virtue of copied designs. Rather than continental influence, I think to appreciate Ezo, you have to look to northern Japanese influence and artistry. This is hard enough to pin-down, without looking for extra-territorial influence. Junichi, regarding Hiraizumi, a slight clarification is needed I think. Hiraizumi as a regional center was created by the Japanese, after expansion into the region had sufficiently derisked the undertaking. Hiraizumi was not an Emishi city which was taken by the Japanese. The points of contact were still strong, and the rulers of the region (Abe and Oshu Fujiwara shoen, among others) had documented direct lineage with earlier local Emishi sovereigns. This was a peripheral settlement, and would have been a cultural crossroads, but the prevalent cultural and political driver was the central Kinai government. There was also a huge Buddhist presence, with temple complexes rivaling Nara. Thus even art produced in Hiraizumi before the sacking would have been strongly influenced by Kinai philophy, craftsmanship and artistry, with the northern element being an overprint or flavor. Thus my point of even the northern influence being hard to pin-down with any certainty. Hiraizumi was all but destroyed during the wars of the late 11th and 12th centuries leading to the establishment of the Kamakura Bakufu. Now only a fraction of the original temple complex remains, and the treasure room was pillaged during the initial sacking. Interestingly, today, the monks are notorious for jealously guarding the complexes and remaining collections. Very little is published on the remaining collections, outside of architectural and statuary studies. Its almost as bad as the Imperial temperament towards excavating kofun. Best, Boris.

-

I'm not a ko Mino collector, but here is a favourite.. Its not very old - Momoyama/Keicho in age, but well executed. Best, Boris.

-

Some more images, grouped by relative age. I have gone out on a limb here, and am showing a few pieces which now belong to others. If anyone prefers an image removed, please PM me. Below is Kamakura to Nambokucho. Worthy of mention is the size of the early pieces. The second set of menuki measure ~9cm. The central panel of the kozuka is silver and executed in repousse. It seems to have been trimmed to fit the new housing, which is made of shibuichi. It is a good example of reuse of likely older bits into kodogu. Nambokucho to Early Muromachi. You start to see more sukashi, and increasingly a similarity to the early ko Mino works. There is a increase in diversity of shapes, but the depth of the menuki start to decrease. There is a subset of Muromachi Ezo menuki which are nearly devoid of sukashi. It is possible that at least some of these could have been used for other purposes, such as ornamental metalwork additions to maki-e boxes. These pieces range in size from about 6 - 9cm. By the late Muromachi, we see the last gasp of Ezo works. They are supplanted perhaps by popularity, perhaps due to cost of production by the ko kinko and ko mino works we are used to seeing. Revivals occur in the Momoyama/Keicho, such as the ko Umetada mentioned earlier in this thread. By the early 1600's the quality of revival work craters, and is not worth talking about here. Best B