Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation since 03/01/2026 in all areas

-

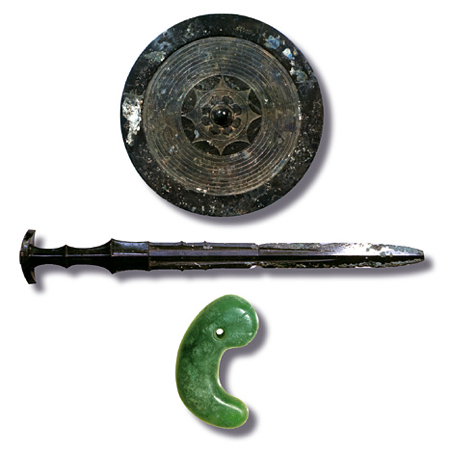

A little while ago, I gave myself the task of learning more about Gyobutsu swords, or the swords personally owned by the Emperor of Japan. When I first embarked on this research, I did not think it would be a very arduous task, like other designations or provenance it just meant doing a little digging but little did I know. Straight from the beginning I got a little unstuck as my first task was to find a comprehensive list of Gyobutsu swords – surely, this would not be that hard to find with so many greats before me, someone must have created a list, written a book, right? Nope, well certainly nothing I found until well after WWII and even then there is no proper definitive Gyubutsu list of swords that were owned by the Emperors of Japan. Emporer Meiji – son of heaven You see back in the day, as a living descendent of the gods, the Emperor was subject to no one and no thing and therefore what he owned was never catalogued in a public way… ever. It was not necessary and certainly not appropriate for the time. Records did exist but they were strictly for viewing within the walls of the Imperial Court. This as a result makes this designation of Gyobutsu probably the opaquest designation that can be given to a sword and the same can be said for Imperial Provenance because whilst some of the records are easily accessible now – most even today are still not. Two swords that fall into the latter category of not having accessible records are the two previous Gyobutsu swords by Gō Yoshihiro. From the Japanese Sword Encyclopedia by Fukunaga Suiken (R.I.P.) we get this information: Kitano-Gō: This sword, crafted by Gō Yoshihiro, is listed in the "Kyoho Meibutsu-cho" (Chapter of Specialties of the Kyoho Period). Hon'ami Kosa and Komasu purchased it from Sakai in Senshu. Kotoku, who had been named after Yoshihiro, attached a 1,500-kan (approx. 1,500 kan) origami (signature). The centre features gold inlay "Emagami Kotoku (monogram)." These characters are said to have been written by Hon'ami Koetsu. In September 1614, Maeda Toshitsune travelled to Sunpu to express his gratitude to Tokugawa Ieyasu for his succession to the domain. Hon'ami Kosa followed him to Nagoya, claiming to be celebrating the succession. Having become lord of the domain and feeling cocky, Toshitsune generously purchased the sword. Years later, while Toshitsune was in Kyoto, he stayed at the residence of Shōbaiin, the Shinto priest of Kitano Tenmangu Shrine, and had the sword tested on the banks of the nearby Kamiya River. Because of its excellent sharpness, the sword came to be called Kitano-Gō, after the place where it was tested. By the time the Kyoho Meibutsu-chō was compiled, the sword's value had risen to 5,000 kan. The Maeda clan kept it at their Edo domain residence. There is a record of Hon'ami Nagane having it maintained in March 1812 (Bunka 9). Marquis Toshinari Maeda On July 9, 1910, Emperor Meiji visited Marquis Maeda's residence and was presented with the sword. The Kitano-Gō is currently kept at the Tokyo National Museum. The Kyoho Meibutsu-chō lists the blade length as 2 shaku 3 sun 5 rin (approximately 69.8 cm), but Maeda family records state it as 2 shaku 3 sun (approximately 69.7 cm), which corresponds to the current length. The curvature is 6/8" (approximately 1.8 cm). The surface has a flowing itame grain pattern and is slightly raised. The blade pattern is a curved straight blade with a small five-point pattern and frayed edges. The blade has a small rounded edge. There are four notches above the monouchi. The center is heavily polished and there are three mekugi-ana holes. However, judging from the burnished blade pattern, it does not appear to have been polished very much. Nabeshima-Gō: This is an unsigned sword written by Gō Yoshihiro of Etchu, listed in the "Kyoho Specialty Book." It was first owned by Nabeshima Naoshige, the lord of Hizen Saga Castle. The sword was passed down to Umitada family from this family, who made an oshigata of the sword. Afterwards, the Umitada family presented it to Tokugawa Ieyasu. It is probably the same sword that was named the ``Koboshikiri-Gō'' presented by Katsushige Nabeshima in 1600. In November 1618, it was gifted to the Bishu Tokugawa family as a so-called Suruga gift. According to the records at that time, there was a slight nick on the blade about 3 inches (approximately 9.1 cm) below the side. It is decorated with a 75 pieces of gold origami, the edges are made of shakudo, the menuki is made of gold-free taku, it depicts a lion with two lions, the tsuba is made of shakudō, the habaki is double-layered, the bottom is covered with gold, the top is made of gold-free gold, and the face and quail eyes are made of gold-free gold. The back of the koji is walnut, and the front is a carving of a lion with three cubs. The small handle was made of shakudo and had an image of a shell in water. Koen Hon'ami has also seen this. On September 21, 1636, when Shogun Iemitsu came to the Bishu residence, Yoshinao presented this sword to the Shogun along with Rai Kunimitsu's tanto. On June 18, 1651, the sword was given to Iemitsu's fourth son Tokumatsu, the future shogun Tsunayoshi, as a relic of Iemitsu. The theory is that the Bishu family gave it directly to Tokumatsu is incorrect. In the second year of Kyoho (1717), Omi no kami Tsuguhira obtained the permission of Shogun Yoshimune and had the shogun's storehouse swords stamped. Among them, he listed as ``Nabeshima-Gō' but it had two mekugi holes and was completely different. Since then, it has been handed down as a treasured sword of the shogun family, but on August 10, 1891, it was presented to Emperor Meiji under the care of Tesshu Yamaoka. After the war, it became state-owned. The length of the blade is 2 shaku 2 sun 65 rin (approximately 68.6 centimeters), Honzukuri, and Iori-bu. The front side of Jitetsu has a large grained texture and stands out, but the back side has a small grained grained texture. The hamon is rich in small shapes, with a mixture of gomoku and kanji. In the ``Kyoho Specialties'' book, there are several places where ``Yubashiri'' is said to be ``a little bit grilled for both Taira and Ho.'' The blade on the front side has a straight edge and is long and curved, but the back side is jagged, sharp, and crumbles, as the ``Kyoho Meibutsucho'' says, ``Kogiri Feng, Odeki.'' The center is highly polished, unsigned, has one mekugi hole, and has a sword-like shape. As you can see first hurdle crossed Fukunaga Suiken has kindly documented evidence that these two Gō Yoshihiro swords were gifted to the Emperor Meiji, a keen sword collector: Nabeshima-Gō presented by Tokugawa Iesato to Emperor Meiji on August 10, 1889 as documented by the Tokugawa Clan. It seems reasonable that the then 26 year old, Prince Tokugawa Iesato, head of the Tokugawa family would document this – at this stage his family was no longer the Shogun for some 20 years, but he was a Prince and the Emperor had just signed the 1889 constitution in February that year, formalising the himself as head of the Empire, combining in himself the rights of sovereignty. Iesato an Eton educated Noble was keen to stay on the right side of the Emperor and apparently he did as he was made a member of House of Peers when it was established a few months later in 1890 and later became its president from 1903 through to 1933. Portrait of Tokugawa Iesato Kitano-Gō was presented by a 15 year old Marquis Toshinari Maeda to Emperor Meiji on July 9, 1900, when the Emperor Meiji visited the Maeda residence in Komaba Park in Meguro, Tokyo, only a short 8km carriage ride east from the Imperial Palace. The Emperor Meiji visited the 15 year old Marquis Toshinari Kōshaku Maeda on this day because less than a month earlier on the June 13, 1900, Toshinari had been adopted as heir of the main branch of the Maeda clan by his father, the former Daimyō of the Nanokaichi Domain in Kozuke province (modern day Tomioka City, Gunma Prefecture) Maeda Toshiaki, even though he was the fifth son. He was named Shigeru at birth but changed his name to Toshinari at his coming of age. As a new Marquis of only 15 years of age he had only ever known the Empire of Meiji and was never exposed to the times of the Shogunate. As a major family in the Empire the Emperor had come to congratulate the new Marquis Maeda. Former Maeda Residence at Komaba Park Great, so we have two confirmed Gyobutsu Gō Yoshihiro blades… so what happened to them, where are they now? Well, both thankfully, as Fukanaga points out, are still very much around with both being stored and occasionally displayed at the Tokyo National Museum but their ownership status is no longer listed as swords owned by the Imperial Family. The official database (ColBase: Integrated Search System for National Museum Collections) lists them both as belonging to the Tokyo National Museum. Colbase: Katana Unsigned (Famous Nabeshima-Gō) Colbase: Katana (Gold Inlay) Emagami Kotoku (Seal) (Famous Kitano-Gō) So what happened? How did these two swords lose their Gyubutsu status and how did they land up at the Tokyo National Museum like so many other swords from the Imperial Collection? The answer, World War II. To understand what happened we need to dig deeper into the story of war debts and restitution after WWII. After WWII the Allied Forces took control of Japan under the command of General Douglas MacArthur who was the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP). His office, referred to as GHQ which stood for General Head Quarters, became the defacto Ruler of Japan from 1945 through to 1952 as the Emperor and Government had to adhere to this office’s orders and instructions. General Douglas MacArthur & Emperor Hirohito, US Embassy Tokyo, September 27, 1945 During this time, we have now all heard about the confiscation of swords that took place and of course this attracts the most attention due to the horror stories of lost National Treasures but this policy of confiscation did not affect the Imperial collection of swords in the same way. As such none of the Emperor’s Gyubutsu swords were confiscated by this means (although many of Emporer Meiji's newer military swords were) but that does not mean he got to keep all of his treasure swords. In fact, as we will see he did have to give most of them away for two reasons: 1. War Reparations through Property Tax 2. Rearrangement of the Imperial Status where the Emperor became a constitutional monarch Let’s talk to War Reparations through Property Tax. After the Second World War, the Imperial Family found itself subject to the new "Property Tax Law" that was enacted in 1946 under the GHQ. For the first time property taxes were imposed on the Imperial family's property, so payments were required to be made. It was a sizeable sum: 3.3 billion yen, or 90% of all the Imperial Family's assets valued at the time. The sum was so large that the Imperial Family could not pay it and they certainly could not take out a loan that large to do so either. So instead, the only option they were left with, being asset rich but now, incredibly cash poor, was to make payments in kind in the form of restitution through the giving away of Imperial possessions, including prized property, art, furniture and treasure swords. The exercise of claiming this tax was carried out by the GHQ through the Japanese tax office. As such the Imperial Family was forced to act with some haste in terms of giving over these possessions. This meant that a lot of the normal procedures and paperwork associated with documenting changes to the Imperial possessions were simply abandoned – the Allied Forces did not care to wait on protocol. The Americans however were not devoid of documentation and as such somewhere in the archives of the GHQ (held at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in College Park, Maryland, USA) or perhaps even the Japanese Tax Office there will exist documents today that detail the specifics of the Imperial possessions and their individual values as payment in kind against the property taxes the Imperial Family owned. NARA at College Park, Maryland It is also almost certain that the Imperial Family will also have some sort of record for this payment, but we will likely never to see any of these documents for a very long time, if we ever, due to the sensitive nature of these taxes and the estimated values of these possessions. It would invite too much scrutiny and pain digging up such a painful part of Japanese history. As a consequence, today there is little to no data publicly available of this historic transfer of wealth and treasures from the Imperial Household to the Nation of Japan. All we know is that a deal was done between the Imperial Family and the GHQ/ Tax Office so that Imperial possessions including many treasure swords of which Nabeshima-Gō and Kitano-Gō forms part, were used as payment in kind to cover the Imperial Family's tax burden that had been levied on them after the war in 1946 and in so doing these two swords and many more treasures were transferred out of the Imperial Collection to the Nation of Japan and were held at several museums including the National Museum (now known as the Tokyo National Museum.) For more details of this tax burden and payment in kind click here. So now we can see that property taxes were the primary reason why the Japanese Imperial Family lost 90% of their Imperial possessions. It is also how many swords including the two Gō Swords, Kitano-Gō and Nabeshima-Gō lost their Gyubutsu status and became the possession of the Tokyo National Museum as care takers of the treasures for the Nation of Japan. This all seems pretty terrible but the story is not over, let’s look at the second loss of Imperial possessions through the unwinding of the 1889 constitution and the establishment of the Constitutional Monarchy. A year later in 1947, the Emperor’s rights of sovereignty given to him in the 1889 constitution were revoked and new constitution was established where the Emperor of Japan became a constitutional monarch. In so doing the Emperor and the Imperial Family became ceremonial figure heads of the state requiring him to relinquish the remaining majority of his imperial possessions under the new arrangements, so that they could be managed by the Nation of Japan. This came into effect on the 3 May 1947 with the establishment of a new Imperial Household Office under the control of the Prime Minister’s Office so that the old Imperial Household Office no longer fell under the control of the Emperor meaning that it was no longer a part of the Imperial Court but instead became a government depart managed by the Government of Japan. Staff were also transferred out of the Imperial Court and numbers were reduced from 6,200 to less that 1,500 staff. The Imperial possessions transferred to the Imperial Household Office therefore were no longer the property of the Emperor but the property of the Nation of Japan. The Imperial Household Office subsequently became the Imperial Household Agency in 1949 and in 2001 this government department moved from the Prime Minister’s Office to fall under the management of the Cabinet Office. These transfers of Imperial possessions in 1947 saw hundreds of Gyobutsu swords moved to the National Museum where they have remained ever since and became the property not of the Emperor but of the Imperial Household Agency on behalf of the Nation of Japan. This transfer left only a fraction of the original Imperial Treasures in the personal ownership of the Emperor and how this was managed remained undetermined until 1989 when the Emperor Showa passed away and just under 80% of his remaining 4,600 treasures including more swords were “donated” to the national treasury under the ownership of the Imperial Household Agency and housed at Sannomaru Shozokan. A set of two Folding screens part of the Imperial Household Agency collection at Sannomaru Shozokan This has left the current Emperor of Japan Naruhito with a very small personally owned Imperial Collection compared to the past. This includes the 3 Sacred Treasures (which without which the Emperor cannot be Emperor), 20 Accessories of Her Majesty the Empress’ formal attire and 50 Imperial Properties that are made up of scrolls, art works, folding screens and 28 Gyobutsu swords that are considered Historic Objects and as such are not subject to the laws requiring Imperial possessions to be transferred to the Nation of Japan but instead will continue to be allowed to be passed down as part of the Imperial Throne. The Three Sacred Treasures of the Emperor; the mirror Yata no Kagami, the sword Kusanagi no Tsurugi, and the jewel Yasakani no Magatama For your benefit listed below are these last 28 Gyubutsu swords confirmed as of 2019’s coronation ceremony: 1. 治天皇御料・今上陛下 山城国久国御太刀 先帝例祭(黒田清隆献上) Emperor Meiji's gift, His Majesty's present: Yamashiro Hisakuni Tachi from the Former Emperor's annual festival (presented by Kiyotaka Kuroda) 2. 明治天皇御料・今上陛下 相模国正宗御刀(名物 会津正宗) 旬祭三殿御拝(有栖川宮献上) Emperor Meiji's personal gift, His Majesty's present Sagami Masamune Sword (Meito Aizu Masamune) Shunsai Sanden Gohai (presented at Arisugawa Palace) 3. 明治天皇御料・今上陛下 備前国助平御太刀 元始祭(岩崎弥之助献上) Emperor Meiji's gift, His Majesty's present: Bizen Sukehira Tachi for the Genji Festival (presented by Yanosuke Iwasaki) 4. 菊御作御太刀 昭和天皇即位礼(黒田長成献上) Kiku Mitsukuri Tachi presented at the Enthronement Ceremony for Emperor Showa (presented by Nagashige Kuroda) 5. 明治天皇御料備前国真長御太刀 春秋皇霊祭(藤堂高猷献上) Emperor Meiji's gift, His Majesty's present: Bizen Province Masanaga Tachi from the Spring and Autumn Emperor's Residences (presented by Todo Takayu) 6. 山城国吉光御太刀 神嘗祭(権大納言徳川茂徳献上) ※一期一振 Yamashiro Yoshimitsu Tachi from the Kanna Festival (presented by Gon Dainagon Tokugawa Shigenori) (Meito Ichigo Hitofuri) 7. 大和国天国御太刀(小烏丸と号す) 新嘗祭(宗重正献上) Yamato Amakuni Tachi (Meito Kogarasu Maru) (presented by Muneshigemasa) 8. 備前国信房御太刀(十萬束と号す) 元始祭(徳川家達献上) Bizen Nobufusa Tachi (Meito Jumanzuka) Genji Festival (presented by Tokugawa Ietatsu) 9. 山城国国永御太刀(名物 鶴丸) 歳旦祭(伊達宗基献上) Yamashiro Kuninaga Odachi (Meito Tsuru Maru) Saidan Festival (presented by Date Muneki) 10. 山城国宗近御太刀 先帝例祭(酒井忠道献上) Yamashiro Munechika Tachi from the Former Emperor’s Festival (presented by Tadamichi Sakai) 11. 上皇昼御座御剣備前国長光御太刀 昼御座御剣 Bizen Province Nagamitsu Tachi, Retired Emperor's Daytime Throne sword 12. 上皇小御所出御御剣備前国包平御太刀 御寝間御剣(徳川家重献上) Bizen Tsunehira, Retired Emperor's sword from his small palace, sword for the sleeping quarters (presented by the Tokugawa Ieshige) 13. 古今伝授大和国天国御太刀 御代々古今伝授の節御佩用 Yamato Heavenly Sword, a sword of transmission from generation to generation. 14. 菊御作御太刀 昭和天皇即位礼控(元田永孚献上) Kiku Gosaku Tachi Copy of sword for the Enthronement Ceremony of Emperor Showa (presented by Eifusa Motoda) 15. 明治天皇御料備前国景光景政御太刀 祈年祭(川村純義献上) Bizen Koku kei kōkei Tachi Meiji Emperor's gift from the Prayer Festival (presented by Junyoshi Kawamura) 16. 大正天皇御料相模国行光御太刀 神嘗祭(伊藤博邦献上) Sagami Yukimitsu Tachi Emperor Taisho's gift from kan’nasai (presented by Ito Hirokuni) 17. 山城国国綱御太刀(名物 鬼丸) 新嘗祭(御取寄せ) Yamashiro Kunitsuna Tachi (Meito Onimaru) from Niname Festival (made to order) 18. 前国則宗御太刀 祈年祭(浅野長勲献上) Bizen Norimune Tachi from Prayer Festival (presented by Asano Chokun) 19. 備前国友成御太刀(鶯丸と号す) 歳旦祭(宮内大臣田中光顕献上) Bizen Tomonari Tachi (called Uguisumaru) from the New Year’s Festival (Presented by Mitsuaki Tanaka, Minister of the Imperial Household) 20. 備前国長光御太刀 旬祭(伊藤博邦献上) Bizen Nagamitsu Tachi Shun Festival (Presented by Hirokuni Ito) 21. 光格天皇御料 相模国正宗御脇指(名物 小池正宗) 賢所御神楽(徳川家斉献上) Sagami Masamune Wakizashi (Meito Koike Masamune) Emperor Kokaku's imperial offering Kashidokoro Kagura (Presented by the Tokugawa family) 22. 後白河天皇御剣 東宮御相伝 賢所御拝 Emperor Goshirakawa's Katana, the Crown Prince’s Sword 23. 豊後国行平御太刀 東宮御相伝 賢所御拝 Bungo Yukihira Katana, the Crown Prince’s sword: Worship at the Kashikodokoro 24. 豊後国行平御太刀 昼御座御剣 Bungo Yukihira Tachi Hirumoza no Tsurugi 25. 備前国長光御太刀 御寝間御剣 Bizen Nagamitsu Tachi, sleeping sword 26. 孝明天皇御料 相模国総宗御脇指 賢所御神楽(津軽承昭献上) Mitsuru Emperor Komei's Imperial Offering Sagami Soshu Wakizashi Kashikodokoro Kagura (presented by Josho Tsugaru) 27. 大正天皇御守刀美作国正守短刀 天皇陛下御枕刀(御誕生の節進ぜられ) Bizen Masamori Tanto Emperor Taisho's Talisman Tanto, (presented to celebrate his birth) 28. 山城国吉光御短刀(名物 平野藤四郎) 皇后陛下御枕刀(前田斉泰献上) Yamashiro Yoshimitsu Tanto (Toshiro Hirano) the Empress's Makura sword (presented by Nariyasu Maeda) As you can see this is a far cry from what was once said to be hundreds or even a thousand plus treasure swords owned by Emperor Meiji. In fact, many serious private collectors of Swords, including many international, now hold even more swords than the Emperor, something that boggles the mind. In my ongoing research I still have not managed to find a definitive list of pre-1945 Gyubutsu swords anywhere. We have scattered sources of information for example the Gyubutsu Tokahu Mei Oshigata by Sato and Numata, that lists the tangs of the Imperial Household Agency owned blades housed at the Tokyo National Museum but these are a snapshot from 1958 when they were already the property of the Nation of Japan. The list of the swords transferred from the Imperial Family to the Imperial Household Office that went on to be stored at the National Museum can be found in a book published by the Tohaku entitled; Tokyo National Museum Centennial History, but again this was published in 1973 which is some time after the swords had been transferred from the Imperial Family to the museum. The Tokyo National Museum Home to many of the Imperial Household Agency’s Collection of Swords In the end no definitive list of Gyobutsu swords pre-1945 was found and as such the quest continues to some degree. (Please feel free to drop a line below with any sources you have found in your time.) Unfortunately, as no Gyobutsu sword past or present will ever be sent to NBTHK (unless the Emperor perhaps allows it) we will never get their expert opinion on any of the swords in any formal way other than commenting on them perhaps in articles by people who once had the rare privilege of seeing and maybe even touching them. This also means we are unlikely to ever see them in any of the current Gyobutsu swords in any formal way. The Ministry of Cultural Affairs is also unlikely to ever publish a list of former Gyobutsu swords due to the nature of how these swords were transferred to the Nation of Japan. So, we are where we are… for now. Before I wrap up, I would like to acknowledge those who helped me with this exercise especially the curator of meitou.info who has been a wealth of information and has been so patient and accommodating with all my questions. We are lucky to have such a wonderful person and resource in this space. I would also like to thank @Hoshi who helped prod me. Finally, I would like to state that this is all my own research and therefore all the mistakes or inaccuracies in this are my own and no one else's - if you feel you have something to contribute or share that I have missed or want to correct anything above please do so below - it will definitely help everyone, especially myself, learn. Thank you.13 points

-

明治十七年 – Meiji 17th year (1884) 春三月 – Spring, 3rd month 秋月胤永兼銘 – Akizuki Kazuhisa (AKA Akizuki Teijiro), also serves as a mei. Ref. Akizuki Teijirō - Wikipedia 贈之以賀 – Present this to celebrate. 野口坤之任 – Noguchi Kon’no, being commissioned as … 陸軍少尉 – Army second lieutenant Ref. 野口坤之 - Wikipedia Noguchi Kon'no was one of Akizuki Kazuhisa's students before he was commissioned to the Army.12 points

-

10 points

-

Now that is bit hefty topic line and I do not really have a standing theory ready for it, nor perfectly accurate formula for calculations. However I have done some measuring in old school way from books and done my own reasoning and thinking. A recent post by Arnaud made me remember what I had tried to do a while ago for few smiths. As many forum members might know ōdachi are the most interesting thing for me alongside big naginata and when I go to Japan those are pretty much the things I seek to look at shrines, museums etc. They are however unfortunately very rare. Of course many of them were shortened into regular sized blades later on. However that brings me to the second problem, there are just huge amounts of long ō-suriage mumei katana attributed to some of the top smiths (and to other smiths as well). In overall so many of them that it will leave me scratching my head. Some massive ōdachi and massive naginata/nagamaki were definately used, however I would dare to believe they were not ordinary weapons that were common to encounter. This is not in any way really accurate data, so do not take it as the truth. However it will give some insight on what I personally feel. For some old tachi it is relatively easy to try to figure out the original length, for some it is much more difficult. For this data I needed to have relatively specific data in order to do the calculations, and of course I do have pictures or oshigata of each and every sword. Now of course for best results I would take pictures of every sword, then put the picture collage to computer and scale it counting pixel to match real life size. I have done this type of thing for naginata in past and it takes quite a bit of time. Someone or AI might succeed in it much faster but sometimes doing stuff like that is fun. I only could of course use signed tachi for this data (I counted in partially signed though if they filled the other criteria). Then I must have the nakago length measurement for the item (this is because many pictures are not 100% in scale in books so I needed to calculate the actual measurements I took) I did measure the gap from munemachi to start of the signature for each ubu sword to be a reference point. There were of course few outliers but I believe smiths signed relatively often in similar placement, and the data would also correlate with this. I also tried to look the signature in relation to ana but I must confess it was getting bit too complicated for me, so as I was not looking that deeply into this I did not have time for everything. Then tried to use logical applying on suriage swords to determine the possible original length. While not perfectly accurate I did get very similar results with my personal method than is listed for few swords by Japanese experts. I did select Tomomitsu and Kanemitsu basically as I like them so much. Rai Kunimitsu was just something I was curious about as there are so many swords (signed and mumei) for Rai Kunimitsu. First up is Tomomitsu there are the 2 ubu ōdachi, and I had only 5 suriage tachi that fill the criteria. As can be seen in graph they weren't ōdachi sized originally. Then for Kanemitsu the first entry is the famous ōdachi Ō-Kanemitsu. In my eyes it was originally slightly bigger than it currently is, my estimate was pretty much the same I have seen by experts in books, amazing sword that I hope to see it at TNM some year. The second ubu is the magnificent JūBū tachi at Fukuyama Museum of Art, tiny bit short of being an ōdachi. As I have not yet seen Ō-Kanemitsu this is so far my favorite Kanemitsu. For Kanemitsu there were 17 other suriage swords and only 1 of them came close to being an ōdachi but it didn't really pass as it was tiny bit short. Lots of very large amazing tachi though. For Rai Kunimitsu there was actually one suriage tachi that was still very long, and by my calculations and observations would have been originally c. 95 cm ōdachi. This is the National Treasure that is held in Kyushu National Museum, I was around 1 cm of the expert length estimate so while not perfect it gets rather close. Other than that one, all were just long tachi that of course many of them were really awesome. This doesn't really give any definitive answers and for myself it just maybe raises more and more questions. I hope someone finds this interesting.10 points

-

9 points

-

8 points

-

8 points

-

8 points

-

I have a few but just picked up this Echizen Kinai piece recently. I like the concave petals.7 points

-

7 points

-

7 points

-

Ok, so I have just purchased the newly translated series of books entitled The Honma Diaries (Kanto Hibi Sho) by Markus Sesko. It is an incredible body of work that gives us incredible insight into Dr Honma Junji's appraisals in English in a series of 10 volumes capturing ever one of his appraisals that he wrote in his diaries from 1969 to 1987. For a study of Dr Honma's thoughts I cannot think of a better resource and is up there certainly with the best money can buy. (So go buy the set today... ) As soon as the set arrived I decided to jump in and focus on my current pet project and immediately started scanning through the books for Gō Yoshihiro blades to read their appraisals - for your reference there are 7 officially appraised Gō blades and then I came across his appraisal 1848 on July 1, 1978 that kind of stopped me in my tracks. Here we have a Tanto that is signed Yoshihiro but the collective wisdom tells us there are no signed Gō Yoshihiro blades and even though the quality of the blade is far superior to Senju'in Yoshihiro the NBTHK decided that it could not be a Gō Yoshihiro blade because of that signature and as such papered it as Senju'in Yoshihiro - although that is not what was said on the paper. When Dr Honma Junji had a look at it however he noted that the blade is more "dignified" and in his considered opinion he thought it may have been attributed to Gō Yoshihiro but when it came time to write the Sayagaki he notes in his diary that he "tentatively" attributed it as Senju'in Yoshihiro. For comparison, I have attached the not so great resolution of the signature from the Oshigata that appears in the book together with signatures Gō Yoshihiro attributed to Gō from: 1. Tōken Kantei Hikketsu, Hon’ami Yasaburō, 1905, Volume 3, p. 129 2. Ōseki Shō, reprint 1978, p. 92 3. Kokon Wakan Banpō Zensho, Volume 12 (3), p. 114 His final thoughts were: "this work is superior in terms of overall quality, hence we have here a very important reference." It is interesting to note this is the final appraisal Dr Honma Junji ever made for a blade he considered to have been made by Gō Yoshihiro. In 1978 (almost 50 years ago) this "Tanto 1848" was owned by Seiwa Kai member Suzuki Yoshio [鈴木義雄]. So what are your thoughts?7 points

-

I went to the Samurai Exhibition at the British Museum yesterday. It was pretty well laid out, with the focus really seeming to be on armour, with some discussion of the weapons used, and the role of the samurai in the Edo period. There was one display with tsuba, so I thought I would share them (two more in the following post). As usual, there was almost no description of the tsuba provided, so if anyone could include comments, origins, etc, then it would be great. The tsuba are really quite nice, with a good variety of themes, some seen before, and others that are less common. I really like the bee tsuba, it reminds me of Klimt.7 points

-

7 points

-

IMHO its a fake. The figures are too stick-like and the mei is wobbly and all over the place. FYI attached is a mei on a kozuka I have. It is identical to my eye to a second kozuka I have with the same theme of people. BaZZa. Here is the kozuka - I apologise for the poor shot. I've been 'gunner' upgrade the hasty photos... And here is a mei that was on a kozuka on the internet some time ago: Here is that kozuka: And here is the text for the kozuka immediately above: Hosono Sozaemon Masamori (細野惣左衛門政守) worked in Kyoto in the early Edo period between Genroku and Kyoho (1688 – 1736) . He used Kebori and Katakiribori mixed with Hira Zogan and often filled the whole plate with his motives of landscapes and rural life. For his time he was quite progressive as he not only depicted sceneries which had been famous from history or favoured by the noble class but chose to show the life of the working class people. Thus we often see workers or farmers going after their daily job in his work. This Kozuka depicts the eight views of Omi province (today’s Shiga Prefecture) also called the eight views of Biwa lake as all the views concentrate around the southern side of the Biwa lake. The theme was derived from the Chinese ‘Eight Views of Xiaoxiang’ (11th century) and came to Japan in the 14th century when it was used in poetry by Konoe Masaie a prince of Hikone. Later it became a subject for artists like Suzuki Harunobe or Utagawa Hiroshige. I do apologise for the brevity of this post, but I have been late to put my two kozuka into a substantive article. Regards, BaZZa (aka Barry 'Gunnadoo' Thomas)6 points

-

6 points

-

Here are two different examples by the second Jingo master. The design has long been one of my favourites and in Shimizu Jingo terms they are known from all five generations and must have been a particular favourite or popular around the time of the 3rd generation Nagatsugu as a great many examples are known to have been made by him. kind regards Michael6 points

-

Map tsuba : from Bonhams sale https://www.bonhams.com/auction/20790/lot/578/an-iron-tsuba-umetada-school-19th-century/ one from the Liebermann Collection. They all look like Umetada school. The British museum one is a map of the world as known then, unusual with the wide border forming a frame. Snake is shiremono - very common Met Museum from the Stibbert in Firenze pinterest6 points

-

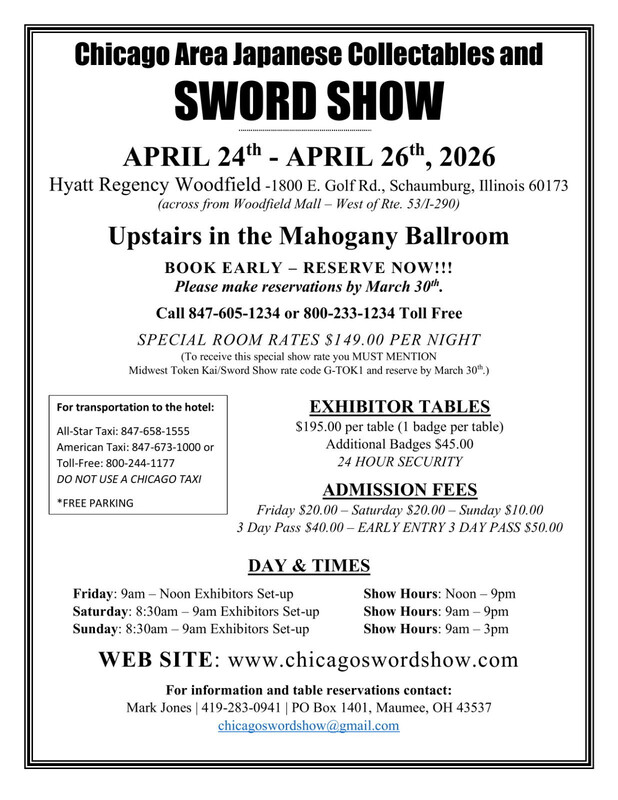

The show is about 2 months away. Perfect time to make plans to attend. More swords, tsuba, kodogu etc in one place than you could see otherwise. Great hand on opportunity to learn. Saturday there will be educational presentations, more details to follow Basic show information here: http://www.chicagoswordshow.com/ If you want to stay at the Hyatt here is a link. Rooms are filling up, if you have trouble booking let me know https://www.hyatt.com/en-US/group-booking/CHIRW/G-TOK1 If you want a table let me know, i usually have a few people who can't make it due to illness/emergency. You can contact me regarding the show at chicagoswordshow@gmail.com Thanks for looking Mark Jones5 points

-

5 points

-

5 points

-

Glad it arrived safely, Matt. This tsuba perfectly exhibits the Tea aesthetics of Furuta Oribe, the leading Tea Master in Japan in the second half of the Momoyama Period. For such aesthetics, Yamakichibei sword guards (the genuine ones ) are at the top, IMHO. Remember, Matt: right of first refusal if you decide to part with this piece! Cheers5 points

-

5 points

-

5 points

-

If I may chime in - the photos do not do this blade justice. It's a terrific tanto, and for this price... Fantastic deal. Soshu-style tantos are not exactly easy to find.5 points

-

Update on the Yamanaka Newsletters V4 NL 01-07 - now available. Albert Yamanaka's Nihonto Newsletters Volume 1 Yamanaka V1 NL01 Yamanaka V1 NL02 Yamanaka V1 NL03 Yamanaka V1 NL04 Yamanaka V1 NL05 Yamanaka V1 NL06 Yamanaka V1 NL07 Yamanaka V1 NL08 Yamanaka V1 NL09 Yamanaka V1 NL10 Yamanaka V1 NL11 Yamanaka V1 NL12 Yamanaka V1 NL12 Extras Volume 2 Yamanaka V2 NL01 Yamanaka V2 NL02 Yamanaka V2 NL03 Yamanaka V2 NL04 Yamanaka V2 NL05 Yamanaka V2 NL06 Yamanaka V2 NL07 Yamanaka V2 NL08 Yamanaka V2 NL09 Yamanaka V2 NL10 Yamanaka V2 NL11 Yamanaka V2 NL12 Volume 3 Yamanaka V3 NL01 Yamanaka V3 NL02 Yamanaka V3 NL03 Yamanaka V3 NL04 Yamanaka V3 NL05 Yamanaka V3 NL06 Yamanaka V3 NL07 Yamanaka V3 NL08 Yamanaka V3 NL09 Yamanaka V3 NL10 Yamanaka V3 NL11 & NL12 Volume 4 Yamanaka V4 NL01 Yamanaka V4 NL02 Yamanaka V4 NL03 Yamanaka V4 NL04 Yamanaka V4 NL05 Yamanaka V4 NL06 Yamanaka V4 NL075 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

I think i found its brother... HERE Slightly different but with same markings..... HERE I suspect that it may be a mass produced tourist piece in the Indo-Persian, and Afghani styles. My parents also bought similar items in Colombo Ceylon, now Sri Lanka Found It ! This style is called the Modern kirpan and is carried by Sikhs. It had traditionally been the full size tulwar sword but reduced to a size of 18inches or less in the 20th century . More info ....HERE4 points

-

Had an enquiry asking for different pics to Aoi. Usually would go out in the back yard in the light but since moving im now overlooked so dont want look like a nutter in the back yard. Mostly taken under the lights of my 90s style kitchen, hope these suffice a bit better, not really good at sword photography.4 points

-

Yes, all kaen boshi are hakikake, but not all hakikake boshi are kaen. Kaen implies a deviation from normal to an extreme proportion of hakikake. When in doubt hakikake is never wrong. I can see why the dealer in question called this one hakikake as would I, if for no other reason than to err on the side of safety. In my opinion there in not enough hakikake to make this one kaen. Yet, there is enough that undoubtedly some would consider it kaen. There will always be varying opinions.4 points

-

4 points

-

I booked my hotel and flights back in January. I did run into an issue with the discount airline I originally used, but fortunately I was able to rebook and resolve everything at no additional cost. I’m very much looking forward to the Chicago show. I’ll be attending all three days and staying for two nights at the Hyatt, where I was able to secure the special show rate. I plan to bring three or four tsuba from my collection for display, sale, or trade. They will be shown at the New York Token Kai club table. Each piece has been with me for many years, and I’ll provide a short write‑up for each tsuba on display.4 points

-

Dear Justin. Nice to see what is on display, thank you. The collection is searchable here,https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/search?keyword=tsuba&object=tsuba&view=grid&sort=object_name__asc&page=1#page-top As with most collections items vary from carefully sought out and purchased by the museum to augment the collection and somewhat random assortments from donations. The labelling is frustrating as it usually states, 'Tsuba, 19th century, made in Japan' unless the tsuba is signed in which case the name is given. However there are still a lot of nice things to look at. All the best.4 points

-

This was sent to me the other day. Posting here unless someone has a reason for me to take it down. (see below) Good afternoon, Orlando Show friends, I hope you are looking forward to our June show as much as we are. If you have already reserved your table(s) and booked a room for your weekend stay – THANK YOU!!!! If not yet, then please don’t delay. The show is growing over past years, thanks to your continued support and from a few new faces from around the country. We are laying out the sales room now because of this higher interest, so if you are coming you MUST let us know. I am trying to have all tables sold by the end of April so I will be taking payments in Chicago if you are still deciding. A few announcements. 1. The show will close a little earlier on Sunday so that we can depart the hotel for another group. As such, we will not plan for special activities on Sunday and will be promoting Friday and Saturday as the core public days. 2. We will continue with our Friday night welcome hour for table holders and are proud to present this year’s special demos and exhibits as: a. Etiquette in handing a Japanese Sword – Joe Forcine b. Orlando Toyama ryū dojo demo – Sensei Bob Lampp c. Exhibit on swords of the Yamato Tradition – Ray Singer d. Florida Tosa no Kai Hōzōin-ryū spear demonstration e. Shaolin weapons (sword) forms – Sifu Marlon Pillisoph f. Ikebana International Chapter 132 Orlando-Winter Park g. Central Florida Bonsai Club display 3. Everyone coming to our show is important, but I’d like to mention here a few new names who will be joining us for the first time to our show this year – Billy and Debbie DeNoia from Long Island, NY, Roger Robertshaw from Texas, and Jack Frost and Stephen Kunemond from Virginia. We expect a good representation of armors, swords, tsuba, ceramics, bronzes…. and Asian collectibles. 4. Remember to book your hotel rooms stay early directly with the hotel either by calling, thru our website, or the link here. https://www.hilton.com/en/attend-my-event/mcohndt-90k-1ac36892-11d1-4cc4-af3e-b772cd3f518f/ 5. It has been requested that a secure ground floor space can be made available to hold merchandise on Thursday evening instead of leaving it in a car or lug it up to an upstairs room. We will consider it, but only if you let us know you’re interested 6. For you first time attendees the hotel charges us for parking at a very reduced rate ($7.00 for overnight or $5.00 daily). Please note this is a gated lot with physical security and it accesses directly into the convention center. 7. FYI, for those flying in - the hotel shuttle can take you to anywhere within a one mile radius at no cost. We are located centrally and less than a mile from the Orlando International Airport and plenty of restaurants Thank you as always for your support of Florida’s only Japanese sword show and we are looking forward to another great weekend of Budo history4 points

-

I have been a member of the Nihonto Message Board since 2006. My love affair with Nihonto spans over 50 years. First time I saw a "Japanese sword" was around 1970 when I saw a couple that a friend’s father brought home from the war. My serious involvement and study of Nihonto began around 1990. The first Nihonto I owned was a gift from a friend. It was nothing special, a suriage Muromachi period blade mounted in a type 98 koshirae. I still have it. In the late 80’s I met Col. Dean Hartley who lived nearby and meeting him became my introduction into the world of Nihonto. Dean was one of the foremost Nihonto scholars outside Japan at the time. Dr. T.C. Ford was another great mentor and student of Nihonto. I spent many weekends at his home studying Nihonto. My website; Yakiba.com has been in operation since the year 2000. Around the time I started the website, I co-owned a small shop in Fukuoka Japan and imported many, many Nihonto. Since the passing of my partner, my focus centers mainly on consignments from clients and friends made over the last 30+ years. *Unfortunately, I have been plagued with website issues over the last year. Currently the site is being rebuilt from the ground up with a new designer and host. Once live I will link to it here. Until then, I will list a few items here on the NMB. If there is something specific you are looking for, feel free to reach out to me as I have many Swords, Fittings and Koshirae. If you have Nihonto or Nihonto related items you wish to sell, contact me and I will be happy to discuss the consignment policy with you. A quick note on consignments: Initial prices are set by the owner, who also have final say on the acceptance of the selling price. It is hard for most consignees to take a loss on items, and as market values change, it can be a difficult reality to accept. With that said, I am always willing to present a reasonable offer on the behalf of the buyer. If you feel a price exceeds your estimated worth, make a reasonable offer. I have seen both sides of this scenario, owners who will not budge and others accept an offer I was sure would be rejected. The point being you never know without asking. *Please limit contact to email only*. Email addresses: yakiba.com@gmail.com or yakiba1@yahoo.com You can find me on Facebook (FB) using the link below. I serve as an administrator for several groups on FB including Nihonto Group, Japanese Tsuba Collectors, International Nihonto Appreciation, and Samurai Sword. Find me on: Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/yakiba.nihonto.9 Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/yakiba.nihonto/ Forms of payment include PayPal, Zelle, Bank wire transfer, and cash. Knowing most of you, you know I have a reputation of honesty and integrity. I look forward to interacting with old friends as well as making new ones. Ed Marshall Yakiba.com4 points

-

Hi @Ben A Harris, You have what looks like a large and imposing sword in those WW2 military fittings. Are you able to take the handle off, and show us the tang? These swords were designed to be disassembled, so fear not. But still, proceed with care and caution. Skip ahead on this video to the time 6:40, for instructions on disassembling a sword in fittings.4 points

-

4 points

-

First off … is this OK to be discussed here? I did see another similar post recently … but I want the Mods to confirm or … I have 2 of these, one ‘square’ like this and the other is a fully round body. Info seems to be dearth on these, but I foind this online -see below - from the IMA (International Military Arms) site. Bit keep these questions in mind, thanks! -Do you concur? -Anything to add or debate/question? -What do YOU think the value is? Now this is an incredible piece of early Ming Dynasty history, circa middle 14th Century. This is the first one of these 8-Shot Hand Cannons we have received and we couldn’t have gotten a better example! The hand cannon, also known as the gonne or handgonne, is the first true firearm and the successor of the fire lance. It is the oldest type of small arms as well as the most mechanically simple form of metal barrel firearms. Unlike matchlock firearms it requires direct manual external ignition through a touch hole without any form of firing mechanism. It may also be considered a forerunner of the handgun. The hand cannon was widely used in China from the 13th century onward and later throughout Eurasia in the 14th century. In 15th century Europe, the hand cannon evolved to become the matchlock arquebus, which became the first firearm to have a trigger. This example was meant to be mounted on a pole, much like the earlier fire lance. This hand cannon has a 4 ½” inch socket which would fit a 1” wide wooden shaft. The center hole on the muzzle area of the cannon is much smaller than the other 8 and is not meant to be fired from. This center hole was meant as a means to keep the spear length shaft secured. All 8 “chambers” have their own individual touch hole just like a regular cannon, making this an early semi-automatic of sorts! Each barrel is mostly clear with a clear touch hole, all inspected with a borescope, though there is buildup from corrosion on the insides. Each of the barrels measures approximately 3 ½” in length. An incredible example of an extremely rare hand cannon dating back to the early days of the Ming Dynasty! Comes more than ready for further research and display. Specifications: Year of Manufacture:14th Century Caliber:about 0.34 inches Ammunition Type:Lead Ball and Powder Ignition: Touch Hole BarrelLength:3 1/2 inches Overall Length:9 5/8 inches Feed System: Muzzle Loading – 8 Barrels The earliest artistic depiction of what might be a hand cannon — a rock sculpture found among the Dazu Rock Carvings — is dated to 1128, much earlier than any recorded or precisely dated archaeological samples, so it is possible that the concept of a cannon-like firearm has existed since the 12th century. This has been challenged by others such as Liu Xu, Cheng Dong, and Benjamin Avichai Katz Sinvany. According to Liu, the weight of the cannon would have been too much for one person to hold, especially with just one arm, and points out that fire lances were being used a decade later at the Siege of De’an. Cheng Dong believes that the figure depicted is actually a wind spirit letting air out of a bag rather than a cannon emitting a blast. Stephen Haw also considered the possibility that the item in question was a bag of air but concludes that it is a cannon because it was grouped with other weapon-wielding sculptures. Sinvany concurred with the wind bag interpretation and that the cannonball indentation was added later on. The first cannons were likely an evolution of the fire lance. In 1259 a type of “fire-emitting lance” (tūhuǒqiãng 突火槍) made an appearance. According to the History of Song: “It is made from a large bamboo tube, and inside is stuffed a pellet wad (zǐkē 子窠). Once the fire goes off it completely spews the rear pellet wad forth, and the sound is like a bomb that can be heard for five hundred or more paces.” The pellet wad mentioned is possibly the first true bullet in recorded history depending on how bullet is defined, as it did occlude the barrel, unlike previous co-viatives (non-occluding shrapnel) used in the fire lance. Fire lances transformed from the “bamboo- (or wood- or paper-) barreled firearm to the metal-barreled firearm” to better withstand the explosive pressure of gunpowder. From there it branched off into several different gunpowder weapons known as “eruptors” in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, with different functions such as the “filling-the-sky erupting tube” which spewed out poisonous gas and porcelain shards, the “hole-boring flying sand magic mist tube” (zuànxuéfēishāshénwùtǒng 鑽穴飛砂神霧筒) which spewed forth sand and poisonous chemicals into orifices, and the more conventional “phalanx-charging fire gourd” which shot out lead pellets. Hand cannons first saw widespread usage in China sometime during the 13th century and spread from there to the rest of the world. In 1287 Yuan Jurchen troops deployed hand cannons in putting down a rebellion by the Mongol prince Nayan. The History of Yuan reports that the cannons of Li Ting’s soldiers “caused great damage” and created “such confusion that the enemy soldiers attacked and killed each other.” The hand cannons were used again in the beginning of 1288. Li Ting’s “gun-soldiers” or chòngzú (銃卒) were able to carry the hand cannons “on their backs”. The passage on the 1288 battle is also the first to coin the name chòng (銃) with the metal radical jīn (金) for metal-barrel firearms. Chòng was used instead of the earlier and more ambiguous term huǒtǒng (fire tube; 火筒), which may refer to the tubes of fire lances, proto-cannons, or signal flares. Hand cannons may have also been used in the Mongol invasions of Japan. Japanese s of the invasions talk of iron and bamboo pào causing “light and fire” and emitting 2–3,000 iron bullets. The Nihon Kokujokushi, written around 1300, mentions huǒtǒng (fire tubes) at the Battle of Tsushima in 1274 and the second coastal assault led by Holdon in 1281. The Hachiman Gudoukun of 1360 mentions iron pào “which caused a flash of light and a loud noise when fired.” The Taiheki of 1370 mentions “iron pào shaped like a bell.” Mongol troops of Yuan dynasty carried Chinese cannons to Java during their 1293 invasion. The oldest extant hand cannon bearing a date of production is the Xanadu Gun, which contains an era date corresponding to 1298. The Heilongjiang hand cannon is dated a decade earlier to 1288, corresponding to the military conflict involving Li Ting, but the dating method is based on contextual evidence; the gun bears no inscription or era date. Another cannon bears an era date that could correspond with the year 1271 in the Gregorian Calendar, but contains an irregular character in the reign name. Other specimens also likely predate the Xanadu and Heilongjiang guns and have been traced as far back as the late Western Xia period (1214–1227), but these too lack inscriptions and era dates (see Wuwei bronze cannon). Li Ting chose gun-soldiers (chòngzú), concealing those who bore the huǒpào on their backs; then by night he crossed the river, moved upstream, and fired off (the weapons). This threw all the enemy’s horses and men into great confusion … and he gained a great victory. — History of Yuan Spread The earliest reliable evidence of cannons in Europe appeared in 1326 in a register of the municipality of Florence and evidence of their production can be dated as early as 1327. The first recorded use of gunpowder weapons in Europe was in 1331 when two mounted German knights attacked Cividale del Friuli with gunpowder weapons of some sort. By 1338 hand cannons were in widespread use in France. One of the oldest surviving weapons of this type is the “Loshult gun”, a 10 kg Swedish example from the mid-14th century. In 1999 a group of British and Danish researchers made a replica of the gun and tested it using four period-accurate mixes of gunpowder, firing both 1.8 kg arrows and 184-gram lead balls with 50-gram charges of gunpowder. The velocities of the arrows varied from 63 m/s to 87 m/s with max ranges of 205 to 360 meters, while the balls achieve velocities of between 110 m/s to 142 m/s with an average range of 630 meters. The first English source about handheld firearm (hand cannon) was written in 1473. Although evidence of cannons appears later in the Middle East than Europe, fire lances were described earlier by Hasan al-Rammah between 1240 and 1280, and appeared in battles between Muslims and Mongols in 1299 and 1303. Hand cannons may have been used in the early 14th century. An Arabic text dating to 1320–1350 describes a type of gunpowder weapon called a midfa which uses gunpowder to shoot projectiles out of a tube at the end of a stock. Some scholars consider this a hand cannon while others dispute this claim. The Nasrid army besieging Elche in 1331 made use of “iron pellets shot with fire.” According to Paul E. J. Hammer, the Mamluks certainly used cannons by 1342. According to J. Lavin, cannons were used by Moors at the siege of Algeciras in 1343. Shihab al-Din Abu al-Abbas al-Qalqashandi described a metal cannon firing an iron ball between 1365 and 1376. of the drug (mixture) to be introduced in the madfa’a (cannon) with its proportions: barud, ten; charcoal two drachmes, sulphur one and a half drachmes. Reduce the whole into a thin powder and fill with it one third of the madfa’a. Do not put more because it might explode. This is why you should go to the turner and ask him to make a wooden madfa’a whose size must be in proportion with its muzzle. Introduce the mixture (drug) strongly; add the bunduk (balls) or the arrow and put fire to the priming. The madfa’a length must be in proportion with the hole. If the madfa’a was deeper than the muzzle’s width, this would be a defect. Take care of the gunners. Be careful — Rzevuski MS, possibly written by Shams al-Din Muhammad, c. 1320–1350 Cannons are attested to in India starting from 1366. The Joseon kingdom in Korea acquired knowledge of gunpowder from China by 1372 and started producing cannons by 1377. In Southeast Asia Đại Việt soldiers were using hand cannons at the very latest by 1390 when they employed them in killing Champa king Che Bong Nga. Chinese observer recorded the Javanese use of hand cannon for marriage ceremony in 1413 during Zheng He’s voyage. Japan was already aware of gunpowder warfare due to the Mongol invasions during the 13th century, but did not acquire a cannon until a monk took one back to Japan from China in 1510, and firearms were not produced until 1543, when the Portuguese introduced matchlocks which were known as tanegashima to the Japanese. The art of firing the hand cannon called Ōzutsu (大筒) has remained as a Ko-budō martial arts form. Middle East The earliest surviving documentary evidence for the use of the hand cannon in the Islamic world are from several Arabic manuscripts dated to the 14th century. The historian Ahmad Y. al-Hassan argues that several 14th-century Arabic manuscripts, one of which was written by Shams al-Din Muhammad al-Ansari al-Dimashqi (1256–1327), report the use of hand cannons by Mamluk-Egyptian forces against the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260. However, Hassan’s claim contradicts other historians who claim hand cannons did not appear in the Middle East until the 14th century. Iqtidar Alam Khan argues that it was the Mongols who introduced gunpowder to the Islamic world, and believes cannons only reached Mamluk Egypt in the 1370s. According to Joseph Needham, fire lances or proto-guns were known to Muslims by the late 13th century and early 14th century. However the term midfa, dated to textual sources from 1342 to 1352, cannot be proven to be true hand-guns or bombards, and contemporary accounts of a metal-barrel cannon in the Islamic world do not occur until 1365. Needham also concludes that in its original form the term midfa refers to the tube or cylinder of a naphtha projector (flamethrower), then after the invention of gunpowder it meant the tube of fire lances, and eventually it applied to the cylinder of hand-gun and cannon. Similarly, Tonio Andrade dates the textual appearance of cannon in Middle-Eastern sources to the 1360s. David Ayalon and Gabor Ágoston believe the Mamluks had certainly used siege cannon by the 1360s, but earlier uses of cannon in the Islamic World are vague with a possible appearance in the Emirate of Granada by the 1320s, however evidence is inconclusive. Khan claims that it was invading Mongols who introduced gunpowder to the Islamic world and cites Mamluk antagonism towards early riflemen in their infantry as an example of how gunpowder weapons were not always met with open acceptance in the Middle East. Similarly, the refusal of their Qizilbash forces to use firearms contributed to the Safavid rout at Chaldiran in 1514. Arquebus Early European hand cannons, such as the socket-handgonne, were relatively easy to produce; smiths often used brass or bronze when making these early gonnes. The production of early hand cannons was not uniform; this resulted in complications when loading or using the gunpowder in the hand cannon. Improvements in hand cannon and gunpowder technology — corned powder, shot ammunition, and development of the flash pan — led to the invention of the arquebus in late 15th-century Europe. Design and features The hand cannon consists of a barrel, a handle, and sometimes a socket to insert a wooden stock. Extant samples show that some hand cannons also featured a metal extension as a handle. The hand cannon could be held in two hands, but another person is often shown aiding in the ignition process using smoldering wood, coal, red-hot iron rods, or slow-burning matches. The hand cannon could be placed on a rest and held by one hand, while the gunner applied the means of ignition himself. Projectiles used in hand cannons were known to include rocks, pebbles, and arrows. Eventually stone projectiles in the shape of balls became the preferred form of ammunition, and then they were replaced by iron balls from the late 14th to 15th centuries. Later hand cannons have been shown to include a flash pan attached to the barrel and a touch hole drilled through the side wall instead of the top of the barrel. The flash pan had a leather cover and, later on, a hinged metal lid, to keep the priming powder dry until the moment of firing and to prevent premature firing. These features were carried over to subsequent firearms.4 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

The best advice is always to buy the blade and not the papers. The internet makes that very hard and many of us are no novices to what you said, the lies of omission, downplaying of kizu, and romanticizing the blade to discount its flaws. A good buyer should know that the fluff is just that. Fluff. Even papers, which are supposed to be a certificate of authenticity aren’t always the source of truth many claim to be. I’ve seen faked papers posted here. I’ve also seen blades faked to match real papers but with a different sword posted here from a notorious Jauce auction. And most disappointingly of all, I’ve seen real swords pass Juyo Shinsa with fake mei to grandmaster smith’s showing that even Shinsa judges have been duped by nefarious means. This shouldn’t come as a surprise as we are in a hobby where gimei blades are abundant and we have a saying “green papers are no papers. Even then, right now on eBay I can go and purchase the only other extant daito signed “Sa” in the world besides the Kokuho daito! My Samonji collection would then rival that of the TNM and most seasoned collectors for only a few hundred bucks!3 points

-

3 points

-

I did, 4 months ago and I have to agree. The depth of knowledge, insight and access to information on well over 3000 blades is unparalleled. The included oshigata is a great resource when studying the blades contained in the volumes. I particularly like the pdf format as it's possible to trawl the content using key words. Great if you're looking for specific smiths or blade characteristics. The Yoshihiro tanto was a standout for me too. As was the Kai-no-kuni Go with the Yamato and Soshuden features (that I referenced in another thread discussing early Go blades with Yamato influence). It's clearly saiha, with monouchi mune-yaki that was introduced by the unsympathetic rehardening. But the overall kitae and extensive provenance demands our attention and possibly points to Go's early sword making influences and origins, if we subscribe to the notion that Go's origins lie in the Yamatoden. However given the tendency to elevate superior works to higher level smiths, could this also be an exceptional example of Senjuin Yoshihiro's workmanship? Like the highest Taima masterpieces going to Soshuden.3 points

-

Amazing work Brett! An amazing writeup on these wonderful treasures. I've really enjoyed your deep dive posts recently and this is yet another great writeup!3 points

-

3 points

This leaderboard is set to Johannesburg/GMT+02:00