Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 03/14/2026 in all areas

-

Hello, everyone! I'm Liang. I currently live in Spain, although I am originally Chinese. Because I grew up using Chinese characters, it is somewhat easier for me to recognize and understand certain aspects of Japanese writing and culture. Since childhood I have always been drawn to finely made objects. Over the years I have enjoyed collecting different things, including amber, Leica cameras, silverware from Britain, the United States, and Denmark, as well as various forms of metalwork, sculpture, and some pieces of militaria. And of course, like many boys growing up, I have always had an interest in knives and firearms. Through this interest in craftsmanship I eventually discovered Japanese sword fittings. I find tosogu truly fascinating — the level of craftsmanship can be extraordinary, and the variety of subjects, schools, and techniques seems almost endless. It feels like a field that one could study and appreciate for a lifetime. While trying to learn more, I came across this forum. I have been reading many discussions here and I really appreciate the atmosphere and the knowledge generously shared by the members. I hope to learn from everyone here.9 points

-

4 points

-

Those are some very nice pieces I would love to have in my collection, gimei or not! Everyone wants the authentic signature but as long as the piece is high quality, I don't think it matters too much.4 points

-

VERY GOOD POST BY COLIN> This is my favorite _half gimei_ Purchased in 2007. Now Tokubetsu Hozon NBTHK. Signed on the front by shodai Norisuke. Signed on the back by nidai Norisuke with his early signature "Norishige". It bounced around Europe for many years as a gimei. I bought it and studied it. Over time and with Tanobe-san help, I came to feel that the 'gimei' mistakes on the front were consistent with the nidai's handwriting. This design was known to be one of the last ones done by the shodai. There is a dated one on record. As the shodai lay ill and dying one winter, it seems the nidai finished the work and partially forged his adoptive dad's signature. Thus, it passed shinsa as a daisaku finished by the nidai. If we didn't have extensive records of the shodai and nidai, this one would have been declared "GIMEI' by the public at large. Judges things by the workmanship. Some people collect signatures, but sometimes you just have to appreciate a finely made piece and ignore the signature. I too like the kozuka of Kansan sweeping. Some of the gold inlay, [on his leggings] is the work of someone very skilled. Nice kozuka. Workmanship is good. --You get sick of it, I will trade you something for it.4 points

-

Welcome, and glad to have you on board. Feel free to share some of your other interests in the Izakaya. We have lots of members interested in your other hobbies too.3 points

-

The question should be, “Can anyone read this eccentric (highly stylized) brush writing?” It’s not easy, Chansen. From a quick glance this is an appraisal carried out in Heisei 2, for a “wakizashi, mumei , Tsunahiro, Sagami no Kuni Jū”. There are a couple of notations (?) and the length of one Shaku and… 3(?) Sun.3 points

-

... and a video of this blade from the Masamune no Sono Ichimon 2024 exhibition Sorry for the quality, the lighting conditions were limited https://eu.zonerama.com/Nihonto/Photo/14796705/599892574?secret=4mw04Yf9fo7i2EYh32MPkN3JO3 points

-

a blade attributed to Naoe shizu Kanenobu refers to the lineage of swordsmith from the Naoe shizu shool (a branch of soshu tradition) Namboku-cho perode (14century) classic shizu style with a nickname kin zogan Gold inlaid signature " Asaraashi Moring storm" Theb Name Asaraashi /morning storm in this case, refer's to sharpness of this blade, whose cutting power is so pure and unstoppable that it leaves no traces2 points

-

On the left are three Kanji Sō-Ten Saku. On the right are five Kanji So-Hei-Shi Nyū-dō. So read the whole long Mei from the right…2 points

-

Hello everyone, I have a strong interest in Japanese sword fittings, especially kozuka. This is my first post here and I would like to share two pieces from my collection. Both kozuka are signed “Joi”, but they do not have papers, so I am not sure whether the signatures are genuine or gimei. The seal on the left kozuka (the Kanzan sweeping scene) is inlaid on a raised silver plaque. I would really appreciate any opinions or comments from more experienced collectors. Thank you. Liang2 points

-

2 points

-

Grev, Hikone is a famous castle town in Goshu (the province of Ohmi) to the east of Kyoto and Lake Biwa, formerly residence of the Ii(ii) Daimyo family. In that castle town area were gathered a line of artisans which came to be known as the 'Soten'. We had a thread here recently on this subject. Authentification advice - Tosogu - Nihonto Message Board2 points

-

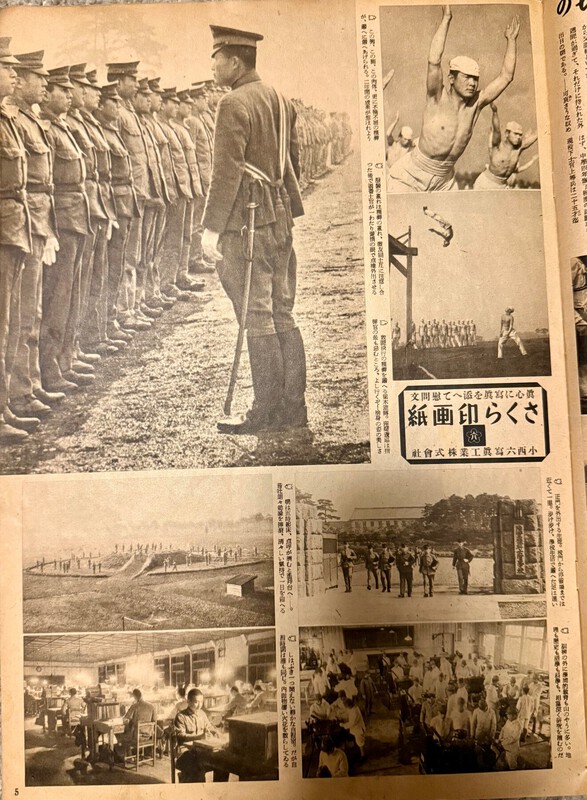

Yes, I completely agree. If I am remembering correctly most of the photos of soldiers with Wakizashi are in China. Well, I bought the photos in China at least. I think I have a few more photos somewhere...2 points

-

Mate - have you ever watched Border Security? Here is Australia we have screening and inspection down to an art form.2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

Matt: What I really like about your pics is that several show ordinary soldiers with wakizashi sized swords as well as a pilot with a regular sized sword. Helps to dispell the myth that a shorter sword is necessarily a "tanker or pilot" sword, as proffered by so many sellers. John C.2 points

-

Just me or does anyone else prefer to view the Oshigata images flipped landscape? Helps me blow them on the big screen to look at them a little more closely - although this is only valuable if I have a good resolution... to echo @Lewis B we need more high res images and I would love to start seeing some of these original images appearing online rather than scanned images as the problem with scanned images unless they come from actual photographs you start to see the printing dots.2 points

-

2 points

-

Reading this story reminded me of an anecdote shared by Ted Tenold many years ago on this very board: I remember a story relayed to me about a Japanese swordsmith that was a visiting guest here in the US. He has made a few small tanto while here and was signing them the morning after a long night of libation. As he was inscribing the mei, he made an abrupt stop from his pace. He grunted and shook his head obviously annoyed by his misplaced strike of a single stroke. Looking up at the observers he laughed lightly and said, "In two hundred years, this is gimei!", then went back about his business. https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/4357-signature-comparisons/#findComment-38825 Useful reminders that for all their artistry and consistency, the great artisans of old were still human and subject to the same pressures as us; a slip of the hand, a bit too much sake the night before, the infirmity of age and sickness.2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

Absolutely, yes. And having two large monitors next to each other means I can view most blades at "actual size" (playing with the zoom until the on-screen measurements match the measurements in the description) across the two of them. "Actual size" in quotes because the proportions will usually be at least slightly warped due to the perspective of the scanner bed or camera lens.1 point

-

1 point

-

Hi @David E, I’m going to relocate this to the ‘wanted to buy’ section.Best of luck with your search for a tanto. Best, -Sam1 point

-

1 point

-

Agree with Brian. Tanto and kirikomi are not a thing (that I have ever seen). (Now waiting for a seasoned vet to pull out a picture from a 47 year old newsletter. :-P)1 point

-

No worries Harvey. Instead of putting them through a resizing program; sometimes cropping the image, or taking a screenshot on your phone will get them small enough to post. Although, as far as I can tell, everything looks good. Looks like a nice cutout tsuba. Interesting scabbard paint. What about the sword made you suspect forgery? Best of luck, -Sam1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

I’m inclined to agree that it’s too thin to be a bokuto. I’m not sure, but is there a difference between bokuto and chato? Yes, it’s got age. No, it has no holes.1 point

-

Hi Chris, This particular topic is many months old, and the original poster has not logged on since January. If you want tariff information, there are several threads about that subject. Tariffs seemingly change with the wind, so what was relevant in August may not be relevant today. https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/53371-importing-nihonto-through-us-customs-and-tariff-info/ https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/55055-can-someone-help-me-understand-the-tariff-sitch-as-of-22026/ https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/54422-tarriff-update-tsuba-from-Japan/ https://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/52348-received-a-blade-from-Japan-in-the-usa-no-tariffs/ Best of luck, -Sam1 point

-

Thank you both for these thoughtful perspectives. I couldn’t agree more. In a way, this is also one of the reasons I am drawn to the Kanzan sweeping scene. Perhaps he is not only sweeping a dusty courtyard, but also suggesting something more symbolic. As collectors, maybe we should not focus only on the signature, but also on the spirit and workmanship of the piece. I would also be very interested to hear more opinions about the design and workmanship of the piece itself.1 point

-

Recently after my last post on the @Wah sent me a fantastic article on many of Emperor Meiji's swords from a special exhibition celebrating a century of the Meiji Restoration at the Matsuzakaya Department Store (Japan's first department store) from January 4-14, 1968, promoted by the Mainichi Shinsha Shrine & Kyoto Shimotsuke Shrine. I enjoyed it so much that decided I translated it and am sharing it here so that everyone else may enjoy it too. From Sword and History Issue 445 (September 1968) Emperor Meiji and Swords (Part 2) Author: Taiko Sasano The Emperor's Military Sword Earlier this year, at the start of the New Year, the "Modern Imperial Family Special Exhibition" opened at Matsuzakaya in Ginza. The number of exhibits was large, and the content was excellent. With such a fulfilling exhibition commemorating the Meiji era opening first, I couldn't help but worry about how difficult it would be for subsequent exhibitions—a concern for others, so to speak. Emperor Meiji's Military Sword, Bizen Province, by Nagayoshi (Chogi) (Tokyo National Museum Collection) In "Modern Imperial Family," two emperors, Komei and Meiji, were avid sword enthusiasts, so several swords belonging to them were on display. Among them were two military swords belonging to Emperor Meiji, exhibited from the Tokyo National Museum. During the sorting of the imperial sword collection immediately after the end of the war, it was initially decided to limit it to fifty swords (according to Mr. Tsunetsujiro Yoshikawa). Since many of the imperial swords have long and distinguished histories, relatively newer swords like Emperor Meiji's military sword were included in the sorting section. It was acquired and is currently housed in the Tokyo National Museum. The first of these gunto swords is a well-maintained large sword bearing the signature "Nagayoshi, Nagafune-ju, Bizen Province." It measures 2 shaku 3 sun and 4 bu in blade length, 8 bu and 8 rin for the curvature and a base width of 1 sun (see photo in black). The jigane (ground steel) has a distinct itame grain pattern and a pronounced shining effect. The hamon (hame) is a mixture of komabure (small swaths) and gonome (five-pointed patterns), with beautiful ashi (astitch) and sunagashi (sand-nagashi) patterns. Small spattered charcoal marks can be seen here and there. The ko (fine lines) have become irregular and have turned into komaru (small rounded patterns). The exterior is saber-style, with the area painted black lacquer in the usual style. As one of the Ten Great Masters of Masamune, this sword has a dignified Eastern appearance and is quite heavy. Therefore, while he favoured it in his prime, he apparently avoided it in his later years. The next sword is a work by Bizen Ichimonji Sukemune. It measures 2 shaku 3 sun 3 bu in length, 7 bu and 5 rin in curvature, and 8 bu in the base, making it appear gentler than the previous Nagagi. The jigane (ground steel) has a finely honed ko-itame (small grain) pattern a fine nie (crystal-like pattern). The hamon (blade pattern) begins with a small, irregular pattern, gradually becoming sparser toward the tip, becoming a straight sword with a slight ashi-iri (foot-like) pattern, but featuring abundant ha-mo (leaf) patterns. The tsuba (guard) is a small katsu (small buckle). The two characters "Sukemune" are vividly inscribed on the blade. The hilt of the saber-shaped sword is made of tortoiseshell, with striking black spots on a yellow background. Count Tanaka Mitsunori According to "Count Tanaka Aoyama" (edited by Sawamoto), this Sukemune was presented by Count Tanaka Mitsunori. The Sino-Japanese War, contrary to world expectations, saw Japan win battle after battle, ushering in the spring of 1928. A high-ranking official from the Imperial Household Ministry was sent congratulations on the victory which in turn resulted in an invite for a representative to visit the Imperial Headquarters in Hiroshima. The representative chosen for the mission was Tanaka Mitsunori, then president of Gakushuin University. A sword lover since his youth, he had a vast collection of famous swords. Among them was a sword by Ichimonji Sukemune, and he decided to use this opportunity to present it. Upon hearing of this, the wealthy Iwasaki Yanosuke requested, "I would also like to present an old Bizen Sukehira. Could you please take it for me?" The two were old friends from the same Tosa domain, and Tanaka readily agreed. Bearing the two swords, he reported to the Imperial Headquarters in Hiroshima on January 14th. Minister of the Imperial Household, Hijikata Hisamoto stood before and abruptly ordered him to bow to the Emperor. There, Tanaka offered his congratulations on the victory and then announced his intention to present the famous sword. Regarding the sword from the Iwasaki family, he said, "This is an old Bizen sword, 800 years old, but it is in excellent condition, as if it had just been made. It is like Minister of the Imperial Household Hijikata, sitting here, he may be old, but he has no grey hair, no hunched back, and is serving His Majesty well. This sword is just like that." He spoke with a touch of humour, and the Emperor burst out laughing, immediately approving the sword. The Emperor seemed to be very pleased with the sword given to him, and he soon used it as a backup. Because, as Tanaka Mitsugao had said, it was in such good condition and therefore it would stay on his waist. The weight was quite a burden though. So, in his later years, he used the Sukemune presented by Tanaka as his military sword instead. It was only 80% of the original habaki size, so it wasn't particularly heavy. Kuroda Kiyotaka Another military sword favoured by the Emperor, due to its lightness, was the Awataguchi Hisakuni presented by Kuroda Kiyotaka. Its blade was 2 shaku 2 sun long, had a 5 bu curvature, and a 8 bu base, making it about the same weight as his previous Sukemune. The jigane (ground steel) has the well-honed Ko-Itame-Hada (small grain) characteristic of the Awataguchi tradition, with a good amount of ji-nie (small crystals in the steel). The straight blade is interspersed with small irregularities, with beautiful foot and leaf markings, and gold lines can be seen here and there. The inscription is powerfully inscribed in the two characters "Hisakuni" at the centre. A typical Awataguchi sword, it truly deserves to be called a famous sword. This is no surprise, as it was originally handed down through the Yanagisawa family and bears a certificate of 3,000 kan from Bunsei 14 (1817). This was a gift from the Kuroda family to the Emperor during his visit to Kuroda when he visited the Capital in Meiji 18, November 1885. Incidentally, Emperor Meiji was well-built. The officer assigned to me during my middle school years graduated from the military academy at the end of the Meiji era. So the Emperor attended his graduation ceremony and said, "I bowed to the graduates, and I bowed to them with the same respect as General Oyama, who was standing behind them." Oyama Gen, a descendant of Saigo Nanshu, was also quite large, but the Emperor was about the same size. The Emperor was also very strong, and in his youth he enjoyed sumo wrestling and horseback riding. He even boasted about it. Consequently, until middle age, he preferred swords with a masculine appearance. For example, the "Kotegiri Masamune" presented by Maeda Sei (Lord of the Kaga Domain) was 2 shaku 2 sun 6 bu in length, which could be considered a standard size, but the blade was 1 sun at the base and 9 bu at the tip, making it quite heavy. There were 12 or 13 military swords, many of which were from the Soshu school, including: Aizu Masamune Aizu Masamune presented by Prince Arisugawa, Honjo Masamune presented by Tokugawa Iesato, (Translator's note: Unsure if there are two swords named Honjo Masamune? The author here is suggesting that a sword by this name was given to the Emperor Meiji by Tokugawa Iesato (1863-1940) and a sword by this name appeared in this special exhibition of Imperial Swords in 1968? Could it be a Hojo Masamune? The special exhibition's catalogue would confirm.) Soshu Masamune purchased from Ogawa Ikko, Samonji presented by Matsudaira Yoshisui, Noshu Kinyuki (unclear) presented by Adachi Masashige. Bizen swords included the aforementioned Ichimonji Sukemune and Nagafune Nagayoshi, Old Bizen Nobutomo presented from Takashima Shinnosuke Meiji 44 (Lieutenant General), Ichimonji Sukeshige presented by Matsudaira Yoshio, Kagemitsu and Kagemasa collaboration presented by Kawamura Sumiyoshi (Marshal). For more information on this sword, please refer to issue 423 of this magazine. The sword used by His Majesty when he supervised the large-scale exercises in Kyushu in the autumn of Meiji 44, 1911 was crafted by Ayanokōji Sadatoshi. It was a large sword with a blade length of over 2 feet and 6 inches, but because His Majesty was tall, it did not seem too long. In addition to the above swords, a naval dagger will also be on display at the "Modern Imperial Family Special Exhibition." It was on display. The exterior is standard, with a white handle and a black front, but the metal fittings feature a 16-petal chrysanthemum crest that shines brilliantly in gold. The blade is a 7 to 8 sun long tanto with an inward curve, and features a typical hamon (temper pattern) with large, irregular five-patterned lines. A favourite sword at his side Each of the Emperor's living rooms had a designated attendant sword. First, in the sleeping room (mikoshi) is the so-called Omakura sword. Its blade is Nagafune Nagamitsu, a 2-shaku 3-sun (approx. 1.5 m) long sword, with a thin golden plate covering the handle. All the other metal fittings were also made of gold, making it a luxurious piece that even the gods shone with golden light. Inner Throne Room Next, in the inner throne room is the so-called Hino-Omashi (sacred seat) sword. This sword was crafted by Kishin-no-taifu Yukihira, and also features a traditional tachi (long sword) design. The metal fittings are made of a quarter-grain alloy, said to have been formed by a mountain that erupted from the ground long ago. Several other swords were also present, but this Yukihira and the previous Nagamitsu were occasionally maintained by the Emperor himself. The Chrysanthemum Thone in the Main Throne room Next, in the main throne room, numerous famous swords were displayed on shelves in the nine-foot alcove and thr next room. Some of the more famous ones include: The one presented by Kuroda which was 2 shaku 3 sun long, and another from Motoda Nagazane, measuring 2 shaku 2 sun 5 bu. The Emperor seemed particularly fond of the latter, and had it fitted with a gold-plated tachi mounting. In the spring of 1893, the master craftsmen of the time, Kano Natsuo and Kagawa Hiroshi, were commissioned to create the koshirae. The gold base used for the sword was excavated from the Sado Gold Mine, with as much gold as possible refined at the Osaka Mint, making it literally pure gold. The mounting was first done by Natsuo, who presented a rough sketch to the Emperor, and the fittings were then approved after it was deemed suitable. Phoenixes are carved into the fittings while other parts are decorated with five-seven and grass motifs. The paulownia wood, in particular, is small, measuring just 2 shaku and 5 sun, so its construction was extremely challenging. Workers reported to the Imperial Household Ministry every day to work on it, but it is said that it took an astonishing 13 years to complete. Sanjo Munechika Odachi: The sword bears the inscription "Munechika," with a blade length of 2 shaku, 5 sun and 9 bu and a curvature of 9 bu and 2 rin. It was presented to the Crown Prince (later Emperor Taisho) by Sakai Tadamichi of the Obama Domain in Wakasa Province during a tour of the Hokuriku region in September 1909, and was subsequently presented by the Crown Prince to the Emperor. For more on this, see issue 429 of this magazine. Tsurumaru Kuninanga Gojo Kuninanga (Tsurumaru): Presented by the Date family during the Emperor's visit to Sendai. For more on this, see issue 429 of this magazine. . Ichigo Hitofuri Yoshimitsu Awataguchi Yoshimitsu (Ichigo Hitofuri) This sword is famous since ancient times and is included in the "Kyōhō Meibutsu-chō", so I will omit its description. Kogarasumaru Yasutsuna Amakuni Yasutsuna Tengu (Kogarasumaru) was presented by Count Sou Shigemasa in 1882. For more information on this, see issues 426 and 441 of this magazine. The Tehata-hosui (SP?) sword was a gift from the former emperor and it comes with a tachi mounting. It is said to have been a favourite of the former emperor, and he was particularly attached to it. The other sword was presented by Marquis Saigo Tsunemichi and has a blade length 2 shaku (approximately 60 cm). It has a high crest, features a grained jigane, and is straight-edged, demonstrating the characteristics of a Yamato sword. It originally belonged to the Honjo family, lords of Miyazu Castle in Tango, but was presented by Tsunemichi, a sword lover. Sōzui Masamune Soshu Masamune (Sōzui Masamune) presented by Duke Tokugawa Iesatu. According to the "Kyoho Meibutsu Cho," this sword earned its nickname from being a favorite of Mōri Terumoto Nyudo Munezui. While in the possession of the Toyotomi family, it was appraised as Sagami Yukimitsu. It was later passed on to the Owari Tokugawa family, and presented to Shogun Tsunayoshi when he visited them in Genroku 11, 1698. It was presented to the Emperor by Tokugawa Iesatu in Meiji 28, 1895, and after the completion of the mounting for the sword presented by Baron Motoda, he commissioned Shakawa Katsuhiro to create a magnificent mounting. Kintano-Gō Gō Yoshihiro (Kitano-go): This famous sword is also listed in the "Kyōhō Meibutsu-chō" Book. It had been passed down through the Kaga Maeda family until it was presented at the Maeda residence by the family in July 1910 during the Emperor's visit. Originally unsigned, it features a gold inlay of Hon'ami Kōetsu in the centre. Uguisumaru Tomonari Ko-Bizen Tomonari (Uguisumaru): This was presented by Count Tanaka Mitsunori. Tanaka Mitsunori, who had previously presented Ichimonji Sukemune, was awarded the title of Count in September 1907 and received 20,000 yen in royal gold. This sword, the famous Uguisumaru, was likely a token of gratitude from Tanaka Mitsunori for this elevation in status, as it was presented in November of the same year to the Emperor, during a large-scale military exercise near Yūki Town, Ibaraki Prefecture. Uguisumaru was originally a long-held sword of the Ashikaga family. In March of the spring of 1489, Yuki Ujitomo of Shimo-no-Kami raised an army, enlisting the surviving son of Ashikaga Mochiuji. By order of Shogun Yoshihisa, Ogasawara Dai Katsutafu Masahan joined the army to fight in the Yūki campaign and fought bravely. He then issued a proclamation to have Mochiuji's surviving son executed. For his service, the Shogun bestowed upon him a letter of commendation and the famous sword Uguisumaru. As the sword has a deep connection to Yūki, where the great battles took place, Mitsumi presented it there at the imperial residence, accompanied by the following poem: "At every battle, I offer the sword that was destroyed at Katsuyama. Not even for a fleeting moment, as I offer the sword before the great master, I will never forget your mercy." After all the battles, the sword is enshrined at Katsuyama Castle. Katsuyama was a castle town in Ono County, Echizen Province, and the castle ruins are now called Nagayama. In Genroku 4, 1691, Ogasawara Tosa-no-kami Sadanobu was buried here, and the ruins lasted until the Meiji period. It was a magnificent sword with a blade length of 2 shaku 6 sun 1 bu and a curvature of 9 bu 5 rin, featuring powerful carvings of the taihi on both sides. For more information on this sword, please refer to issue 43 of this magazine. Bizen Tadamitsu: This swas originally a important sword of the Aizu Matsudaira family, but was given to the Yokami family as a gift from the family. Bizen Mitsutada: There was a 2 shaku 2 sun sword presented by the Hachisuka family as a gift from the family's successor, and another sword with a long inscription "Bizen Province Osafune Mitsutada" presented by Iwasaki Yanosuke. The latter, Osafune, is particularly valuable as a research resource. In addition to the Uguisumaru, another Tomonari was also presented by the Sakai family of Himeji. Keeping a Water Dragon (Suiryuken) (Tokyo National Museum) The Water Dragon ken (Suiryuken) was originally a part of the Shosoin Repository, but was apparently kept at the Imperial Palace during maintenance in the early Meiji period. It is a straight sword with a sharp edge, but the surface is smooth and has been tempered. The exterior was painstakingly crafted by Kano Natsuo, with a golden dragon on the hi-ai and kashira blades and a silver wave pattern on the edge. For this reason, it was named the Water Dragon Sword. While the blade's artistic merit is naturally inferior to the famous swords mentioned above, the Emperor likely treasured it because of its academic value as the birthplace of the Japanese sword. The Golden Dragon the scabbard Contemporary swords—perhaps more for the encouragement of swordsmiths than for appreciation—were also kept in his possession by swords made by Gassan Sadakazu and Miyamoto Kanenori. Sadakazu was particularly highly regarded and highly trusted by the Emperor. While I won't be listing just one Myochin ornament, I'll add a final note about the story of how the Emperor took a liking to an ornament made by Myochin, a renowned armor maker. In 1883, an art exhibition sponsored by the Japan Art Association was held at the office of Hibiya Daijingu Shrine. The Emperor, who loved not only swords but also paintings, sculptures, and other fine arts, attended the exhibition. At the time, most of the treasures handed down through the generations were still kept secret in the homes of former daimyo and nobles. Among the exhibits were some of the finest examples, making for a truly magnificent exhibition. Among the exhibits was an iron dragon exhibited by the Matsudaira family, lords of Mezuyama Domain. It was about seven lengths long, hammered out of iron, and each of the dragon's scales was movable, even down to the tips of its claws. After the Meiji Restoration, when armour orders suddenly dried up, Myochin, who found himself bogged down, created this "stretchy dragon," inspired by armour-making techniques. The Emperor seemed to be very pleased with this, and even after he had retired to the resting place, he ordered Tokudaiji, the Grand Chamberlain, to "call for the dragon." When it arrived, he was playing with it with great interest and desire. This incident was reported to be one of the greatest in Japan. Iron Dragon by Myochin When Sano Tsunetami, president of the Art Association, informed Matsudaira-do, the owner of the work, he was so honoured that he immediately offered to present it to the Emperor. Then, in the following year, another event was held at Tsukiji Honganji Temple. The Emperor also made a visit to that event. After the morning viewing, lunch was finally served in the great hall. There, in a large water basin, five feet in diameter, was a large loquat tree in bloom, with a crab attached to it. After lunch, as he was browsing the room with a toothpick, the crab suddenly caught his eye. He stood up, approached the wooden basin, and picked up the crab. His limbs then began to flap rapidly. With a smile on his face, "Wow, this is well made," he exclaimed in a magical voice. In fact, this was also Myochin's work. An antique dealer named Wakai had purchased it from somewhere for the princely sum of 200 yen (in those days), boasting that he could sell it for 600 yen to a foreigner. The Emperor brought it back to the table and repeatedly praised its quality, prompting Sano, chairman of the association, who was standing nearby, to consult with Minister of the Imperial Household, Hijikata Hisamoto, and propose presenting an offer to Wakai. "It would be a great honour if Your Majesty were pleased," he said. The Emperor immediately agreed. Upon hearing the offer, the Emperor seemed delighted; he put it in his pocket without wrapping it in paper, and took it home. His demeanour was like that of a child buying a favourite toy. Iron Crab by Myochin The Myochin family, whose centuries-old family business had been snatched away by the progress of time and whose fortunes had been sunk, must have felt as if a lost tree had blossomed upon hearing this story.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

This leaderboard is set to Johannesburg/GMT+02:00

.thumb.png.4c5df79fec171b2dc4a23af38e280a4d.png)

.thumb.jpeg.76c486bbedac97918bc9076001300584.jpeg)

.thumb.jpg.d7558d0e52607a46ed6aace10fea4f20.jpg)