Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 09/16/2024 in all areas

-

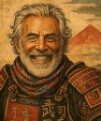

I had the pleasure of meeting Manazu Hitoaki today and watching him work in his home in Osaka. It was a fascinating experience that significantly deepened my understanding of the sword polishing process. Despite his immense skill, he is very humble and spoke only a little English. Fortunately, his apprentices were more than happy to translate and quickly mentioned that he is one of the finest sword polishers in Japan. Some interesting facts stood out during the visit: Hitoaki learned the art of polishing from his father at the age of 15 and has been improving his craft for 58 years. Hundreds, if not thousands, of blades have passed through his hands. Currently, the demand for his services is so high that customers face a two-year wait. He works diligently, more than 10 hours a day, to complete each sword on time. His rate is 20,000 JPY per sun (1.3 inches/3 cm). One of his apprentices eagerly explained the process and the stones used. He has been training under Hitoaki for eight years but still considers himself a beginner. He mentioned that he wouldn't charge more than 8,000 JPY for the same polish as his master. As an amateur knife sharpener myself, I was curious about how they maintain the niku of the blade during polishing. They explained that they work on a very narrow section of the blade at a time, gradually transitioning down the convex surface toward the edge in small increments. Each section is completed before moving on, rather than working in long sweeping motions. Their ability to assess a blade with such precision is astounding. The apprentice handed me a blade and asked me to hold it to the light, pointing out that it was uneven. Despite my best efforts, I couldn't see any imperfections. It really highlights the incredible attention to detail required in this craft. Much of their skill is visual; they don’t count their strokes on the stone but continuously check the blade until they are satisfied with the result. It’s quite remarkable. Hitoaki shared that, despite his best efforts, he has never delivered a sword with a perfect polish, there’s always something he feels could have been improved. He also mentioned that, though the old grandmasters are long gone, he continues to learn from them by studying the swords they polished. This is a vital part of his work, as he strives to adapt his polish to each blade, taking into account its era and style. If the current polish is good, he aims to replicate it in the same way. A very interesting experience that I won't forget.14 points

-

This was on the NMB before so just an update after restoration and received yesterday Original info when first posted so there may be some updated info. 7ft 5inch length complete - Blade around 15" - Tang around 15" Circa 1761 Your pole arm is well balanced and has good line or shape and length. Hamon curls over the kissaki and down the mune for some length. Lower hamon looks like horse teeth pattern while upper is wide suguha. Polish by Les Sheppard New saya and pole refurbished by Mike Hickman-Smith Before and after polish Only a small amount to be seen of the pole in these two image A majestic new saya - glorious texturing An idea of the overall size (I'm about 5'10"5 points

-

I wish it was! The blade I held was one that one of his apprentices was working on, an early Edo era sword. The other one Hitoaki was working on we didn't talk about, but I'm assuming it's a very expensive one. With so much demand for his skills, he needs to draw the line somewhere, so he only works with the finer swords. One funny thing I forgot to mention. I asked one of the apprentices why he started learning this art. He said it's because he is a martial arts teacher, in iaito, battojutsu, etc. and it's a good extension of his business to be able to provide polishing for his students. He went on to explain that he uses a Muromachi era katana for cutting. Which I mentioned would never be done in Europe or USA. It was the first time he heard that the Chinese make fully working shinken for as low as 120 USD, they were laughing and couldn't believe it. I went on to show them some pictures of ryansword which they were not impressed by, other than the low price. Later on we went to the club and tried some tameshigiri cutting with that Muromachi katana. It was very beat up and slightly bent halfway down the blade. It was still a cool feeling to cut with a 500-600 year old katana. And the coolest part was probably to meet their grandmaster, in his 80s, he's a descendant from a long line of Samurai who has passed the swords skills down, dating all the way back to the Edo period.5 points

-

5 points

-

@Bruce Pennington @Kiipu In 成瀨関次(Naruse Sekiji) 's 實戰刀譚(Tale of Practical Combat Swords) It was mentioned that swords were made from old car springs in China, and they became quite popular due to their excellent cutting ability. この刀に首をひねっている頃、それは昨年(十三年)の三月の事で、 兗州の兵器修理班の鍛工場で、工員(制規上軍刀の吊れない人達)が、 日に日に危険にさらされてくるので、必要に迫って、 廃物の古自動車のスプリングを利用して刀を打った。 もちろん鍛えもせず、焼いて延ばした上一様に焼きを入れ、 それを適度に戻したもので、 自分の助手をしてくれていた加古という鍛工軍曹(その当時伍長)が指導した。 加古軍曹は、愛知県小牧に住む刀匠で、造刀については深い研究を積んでいた。 そうした焼きの刀であるから、もちろん刃紋もなく、 若い人達の手に合うようにというので、ある刀のごときは元身巾が一寸二分、 重ねが二分二、三厘もある大切っ先の浅反り二尺三寸、 虎徹の大業物そっくりなものができ、それに木工場で楊柳材の鞘を作り、 軍刀修理場で外装を引き受けて、とにかく吊れるようにし、 いつ敵襲があっても心配ないという事になったが、 その刀が不思議に粘硬で何を切ってもよく切れる。 ある兵隊が戦場で試したが、骨までズンと斬れたというので、 にわかに“兗州虎徹”の名が高くなって、 あちこちから希望者が殺到するという有様であった。 Rough transtale: Around the time I was puzzled by this sword, which was in March of last year (13th year of Shōwa), at the blacksmith workshop of the weapons repair unit in 兗州 Yanzhou, the workers (who, due to regulations, were not allowed to carry gunto) were increasingly exposed to danger day by day. Out of necessity, they forged swords using the springs of discarded old automobiles. Of course, without any proper forging, they simply heated, stretched, and then uniformly tempered the metal before returning it to an appropriate hardness. The process was overseen by a blacksmith sergeant named Kako (a corporal at the time), who had been assisting me. Sergeant Kako was a swordsmith from Komaki, Aichi Prefecture, and had conducted deep research into swordmaking. Because these swords were tempered in this way, they naturally had no blade patterns. However, to suit the hands of younger people, one of the swords had a blade width of approximately 1.2 inches, a thickness of about 0.22 to 0.23 inches, a shallow curvature, and a length of 2 shaku 3 sun (about 70 cm), resembling a large, finely crafted 虎徹 Kotetsu sword. A scabbard made of willow wood was crafted at the woodworking shop, and the sword was fitted with external fittings at the gunto repair shop to make it wearable. This arrangement ensured there was no worry, even in the event of an enemy attack. Strangely, these swords were resilient and hard, and could cut through anything with ease. One soldier tested the sword on the battlefield and found that it cut cleanly through to the bone. This led to the sudden rise in fame of the 兗州虎徹'Yanzhou Kotetsu,' and soon, requests for these swords poured in from all over."4 points

-

If you don't own any of these books, you should! Markus has done an outstanding job putting these together. Collectors and enthusiast today are so lucky to have so much information available in English. It hasn't been that long ago that there were only a few basic beginners books in English by Robinson, Yumoto, and Hawley. Then AFU, Harry Watson translated and published a few welcomed titles such as the Nihonto Koza 6 volumes, and the Translations of Fujishiro's. Then Nagayamas Connoisseurs Book of Japanese Sword hit the stands and was a welcome addition. Markus has made many titles available in English, both hard copies and e-versions. E-books are great once you start using them. I was a hold out, a die-hard who believed in only having real books, hard copies. And I still like the hard copies, however the ease of use with the e-books will convince the hardest of hard asses of their value. As pointed out above using the search function makes thumbing through pages much reduced. With 99% of research, I start with Markus's e-books, and while I may still follow up with hard copy references such as the many Taikans, I find the e-books invaluable.2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

Hey guys, Not sure if this belongs in this section or not but I have been waiting forever for Markus to put his books on sale. If anybody else is in the same boat, Markus is doing a 50% off sale again till September 15th https://markussesko....-end-of-summer-sale/1 point

-

1 point

-

These sword are made in China by battlefild Japanese smith for Japanese troops.1 point

-

Ran across this a few days ago while reading Dawson's book. The quote is coming from a picture caption and is easily overlooked. Dawson, Jim. Swords of Imperial Japan, 1868–1945. Cyclopedia edition. Stenger-Scott Publishing, 2007. Page 156.1 point

-

Cross-Reference Theater-made Gunto1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

Yes, I have already gleened some interesting research leads for my new sword after reading up about Yamato and Soshu Gokaden. Invaluable is the correct word.1 point

-

1 point

-

Hello Carlo, Usually, the lengh of the sword match your size, and in unsheat and strike technique like in iaido, opponents can evaluate the speed of each others by eye-mesuring the lengh of the saya. A short sword can surprise the opponent and let more time to strike. Or maybe having a big saya was like having a big car today... I'm not in backroom of sellers but I suppose that some can sometime cobble Koshirae and swords if they luckily find saya with the same sori and koiguchi that fit the habaki. Suriage swords get a new habaki with new dimensions, and it overall shape is modified. I don't think the sword keep it original koshirae Take my answers with a pinch of salt as I'm a very beginner.1 point

-

There looks to be a little "Chinese whispers" confusion between Hawkshaw's description and the V&A Hawkshaw states "two {2} boys" no mention of 'Chinese' origin - one carrying Hotei's hat. Which would suggest the boy on the back has the hat, as I can't see the one on the omote with it - not that the image is very clear. The V&A states "three {3} Chinese boys, one, on the reverse, bearing his hat. Well we don't have the ura view so it is not possible to be certain, but I would think Hawkshaw's description would at least get the number of 'boys' correct. For more information you know you can email the V&A and ask for either an image or a more accurate description - they don't bite, but they can take their time answering. While talking to them you might suggest they put some effort into their records and give a few size measurements and present the tsuba images with the omote view in their search engine and not the numerous ura views! Oh and let them know they harbour a nice selection of cast reproductions! [Far be it from me to criticise the technical skills of such an illustrious institution ] Marjolein de Raat <m.deraat@vam.ac.uk> Marjolein de Raat Assistant Curator East Asia1 point

-

1 point

-

I rarely buy ebooks as I generally find them less satisfying to use and read, but I took advantage of this sale a week or so ago to buy the Meikan and Swordsmiths ebooks (amongst others), and I'm actually really impressed by how useful the format is for references/data. Not only can you search the entire pdf using ctrl+f (which is very useful for finding references to particular swordsmiths), but you are also able to zoom in on mei and other characters, which makes it a lot easier to compare the kanji. Thanks for people mentioning it on this and another thread, or I would have missed out on this1 point

-

They don't make it easy but I found all of them except for Hotei which the V&A don't seem to have a current image of - they can run but there is nowhere to hide! Some images are still very grainy. The Tiger tsuba in that image: https://collections..../O199603/tsuba-soyo/ M.20-1913 "This one is made of shibuichi, an alloy of copper and silver normally patinated to give a wide variety of colours from silver to brown as well as a range of greys. It is encrusted with a tiger and a leopard which are gold with shakudo stripes and spots. Shakudo is an alloy of copper and gold generally patinated to a rich black colour. Beneath the animals are tall bamboo, also of shakudo, touched with gold, and on the reverse is a second tiger and bamboos similarly rendered." Length: 8cm Width: 7.45cm signed Soyo, Yokoya school, probably ca. 1700-1800 M.465-1916 - YOKOYA Kozuka no other information. M.464-1916 - YOKOYA Kozuka no other information. M.463-1916 - YOKOYA Kozuka no other information. M.259-1911 - YOKOYA - Purchased from Yamanaka & Co. (127 New Bond Street, W.), accessioned in 1911.1 point

-

柳川正心作之 – Yanagawa Shoshin (reading?) made this. 昭和十年正月 – Showa 10th year (1935), January 於東都三縁山麓東海辺 – At the vicinity of Tokyo San’enzan, east seaside I think San’enzan means Hoshuin temple (宝珠院) in Tokyo. Ref. 宝珠院について | 増上寺塔頭 三縁山 宝珠院 (hoshuin.jp)1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

Looks like a surname 大野 (Ohno, or Ōno). The bit under those two would be the given name, but I can't make it out.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

That is called deceitful. If you sell something and you know for a fact that it's gimei, or not made in Japan, and you don't mention that claiming "the buyer should know what he's buying" then you are being deceitful. Let's not make excuses for these guys.1 point

-

1 point

-

The left side should be 住吉太神宮奉以剱余鉄 Made with steel left over from the making/dedication of a sword for Sumiyoshi Taisha (shrine).1 point

-

神力丸有續作之 = Jinrikumaru Aritsugu made this Markus Sesko's Swordsmiths of Japan has the following entry: I can't decipher all of the writing on the other side, but it starts with: 天下太平 = peace and tranquility for the whole world 武運長久 = long-lasting good luck in war1 point

-

Hi All, Just got this Shin gunto in a black leather covered saya, Non pierced tsuba, full set of 8 seppa all with the number 25 stamped on them plus another small inspection stamp. The nakago is signed (I think) Shimada Yoshisuke. No Seki or Showa stamps The only stamp it has is a warrior stamp. For interest, Here is the Signature Hamon And finally tsuba and seppa stamps All the best1 point

-

None of the photos allows me to be sure. I also have a tendency to say 'water quenched', but there is a slim chance the polisher did a good job with HADORI concealing the HAMON. I cannot see NIE or NIOI clearly, so it remains open in my opinion. Concerning photos, to be helpful, they should be: - precisely focused and not blurry - made with a dark, non reflective background for good contrast - made with light from the side (may not apply for HAMON photos) - made from directly above (not at an angle) - made with correct orientation (tip-upwards, especially NAKAGO photos) - without HABAKI but showing the MACHI and NAKAGO JIRI - made in high resolution to see details - showing details of the sword like BOSHI, HAMACHI, HAMON, HADA, NAKAGO JIRI etc. - presented as cut-outs so very little background is shown If you cannot supply good photos (.....these photos are all I have from the dealer..../ I do not have a good camera but only an old mobile phone.... ), DO NOT POST THEM. They will not be helpful.1 point

-

1 point

-

The lineage chart of Hiromasa courtesy of @Stephen. Yoshū Hōjō-jū Hiromasa katana in shingunto koshirae1 point

-

Closed the deal and the Hiromasa will be coming home with me. Thank you everyone for the information and advice. I was about to let this one go!1 point

-

Hiromasa 博正 was from Ehime Prefecture 愛媛県. The 昭 stamp was only used in Gifu Prefecture. So it would be impossible for it to be that stamp. For more information about Hiromasa and Ehime Prefecture, I would suggest taking a look at the monograph below. Showa Period Swordsmiths of Ehime Prefecture1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

Agree. That was likely a star stamp, and this looks like a nice Gendaito.1 point

-

The location you marked is usually where the "Star" stamp was located. If the sword came via Japan in the postwar years, the "Star" stamp could have been removed, so as to register the sword with the authorities. Wartime stamps were frowned upon, including the "Star" stamp.1 point

-

There have been excellent posts made above. I think I will just expand this with various examples, as I will have plenty of those to add substance to some of the various points made in posts made to this thread. I made the Hizen Tadahiro comparison just to show some variety. Given they would all be priced equally I would personally choose the one with horimono & koshirae. However these swords are all of size and shape that I would not buy. To me personally I do not find this shape & size interesting and I would look for something else. Like Jacques I don't like to talk about the price of items that much. Of course I am in fortunate/unfortunate spot I cannot buy anything for several years, so for me it would all be speculative stuff anyways. And I do think sometimes we might get too attached to attribution the sword has been papered to or the level of papers by organization etc. Historical provenance is highly sought after, yet blades with proven historical provenance are pretty difficult to obtain to the collection. I am currently doing lots of research on provenance of famous old swords and there are still lots and lots of blades that have varying from of provenance. Sometimes I am not absolutely certain how the Japanese experts can connect the dots on some swords & provenance but I bow to their authority. I have only quite recently started being fascinated with this and there is so much to research and learn, I am bit shamed to admit I have previously overlooked this subject. Blades with proven provenance will be available for buying but they are often high quality items which of course puts them in expensive price bracket. I completely agree what @dyn @Mushin wrote about zaimei & mumei earlier in the thread. However there can be curveballs where other factors override the signature. For the smith Rai Kunitoshi, here is a signed tantō: http://web.archive.o....net/SHOP/O-225.html that was listed for 2,7M asking price, and here is a mumei tantō attributed to him: https://eirakudo.sho.../tanto/detail/750496 that was 3,5M asking price. Both items being Tokubetsu Hozon, and in my opinion they are now at their current end level with NBTHK classification. I couldn't see either of them going any higher. Small disagreements with attributions are perfecly understandable, as kantei for mumei blades is extremely difficult. Something like Mihara Masaie vs. Aoe I could very well understand. Here is another example that I found interesting as it was long very old tachi https://yushindou.com/生ぶ無銘太刀(伝古青江)(古波平)白鞘/. NBTHK attribution was Ko-Naminohira and NTHK attribution Ko-Aoe. Now while they might seem very different to me there is not too big difference between them. If I would had somehow acquired that item, would had been fun to send to Tanobe for 3rd opinion and see what he thinks of it. Unfortunately I am not yet that aware of NTHK attributions and I only have 1 of their 4 Yushu books. I plan to get all of them some day. However there are items with both NBTHK and NTHK attributions. Some of the famous so far might be Norishige tantō, Motoshige tachi, Yasumitsu tachi that are both Tokubetsu Jūyō and NTHK Yushu. Also I think there will be very high level experts in Japan even if the old guard passes. Of course often in Japanese way the students feel they can never surpass their teachers. However I would give props to modern generation of NBTHK staff too, reading the Jūyō setsumei, Tōken bijutsu magazine etc. I feel comfortable with their expertise as it far surpasses mine. Also what I have heard there are multiple unaffiliated experts in Japan too, and they teach too, so I feel confident the next generation of sword researchers keep it going. I have never met any of the top Japanese experts, just read their knowledge from books and I think same will happen in the future too. While the old experts had/have their mountain of knowledge, they were generous in sharing it and we have ever expanding amount of data in various easy to access forms currently. While it is possible some information will be gone, there are new things being discovered and researched.1 point

-

Putting aside the side issue of Tanobe and "expert panels," (which, BTW, Tanobe oversaw for many, many years while at the NBTHK where he once was the head researcher, ie an "expert,") there is another factor that helps determine blade value: the condition of the nakago, or the tang. Nakago are often overlooked, especially by newbies, but I've seen the value of swords with great workmanship plummet when the nakago was badly deteriorated by water or fire damage, or if it were horribly disfigured by a clumsy shortening process. Likewise, a blade in which the nakago as been "lengthened" by moving the machi up the blade (machi-okuri,) will also impact value. In short, anything that alters the "original vision" of the smith -- reshaping kissaski (sword tip) , changing funbari (blade taper) or shortening the blade -- all can impact the price. That is why among Juyo blades and better, naginata nioshi (naginata that have been reshaped or "corrected" to be a sword) are always more affordable than unaltered Juyo blades by the same smith. Why? Because the changes altered the smith's original vision of the blade. Additionally, what's on the nakago can increase or decrease a blade's value. For example, a blade with the name of the original owner on the nakago can increase a sword's value, even moreso if it was an historical figure. I recall a blade listed on AOI Art a few years back that was a signed Hasebe with an inscription in gold inlay that it once belonged to Tokugawa Ieyasu's father. The blade wasn't on the AOI auction site for but a few hours before it was pulled, presumably by somebody willing to pay way more than the opening bid price because of this incredible information on the tang. In the case of Sue-Bizen smiths, full signatures, called Zokumyo Mei, that include a smith's full name and title, are deemed more desirable than generic smith inscriptions. Thus a blade signed Bizen no Kuni ju Osafune Jirozaemon no Jo Katsumitsu is going to cost you considerably more than a blade signed simply Bishu Osafune Katsumitsu, even if it is papered to Jirozaemon Katsumitsu. Blades with signatures and dates, or nengo, also tend to command higher prices than a blade with just a signature. In fact, the Japanese consider blades with inscriptions such as dates on the ura side of the blade to be "precious." Rarely, the nakago mune can also be inscribed with information, adding to it's allure and price tag. So, just to recap, if you have two katana of equal nagasa and quality by a famed smith such as Echigo Norishige, the one with the original unaltered tango will command a bigger asking price than the one that is suriage, as long as all other things are more or less equal. Likewise, if both are ubu and signed, but one is signed AND dated, that will command more money. The same is true if the signature on one is better than the other because of a water damage nakago. Often it's hard for new collectors to understand why the part of the blade hidden under a handle is so important, but it is. The more you get into the hobby, the more things you learn about why one sword might command a higher asking price than another that is similar. There are many things to think about before you plonk down you hard earned cash on a sword. That said, the reality is not all of us have the resources of Elon Musk, and often we mere mortals have to settle for a blade that is less than perfect because of what we can afford. But at least we can understandn the things that make the difference in the ask, and can even help us understand why one sword was awarded Juyo or Tokubetsu Juyo status and another did not. These things can also help us in negotiating better prices.1 point

-

swords as a hole i think are strong, if there military swords of good conditon then the markets good.1 point

-

1 point

-

Thank you very much The one from aoi is mine and I noticed that the mei was thicker than other of his mei and very unusual so I was surprised. The one is very similar. Here's a comparison from left to right : Mine dated October 1936 - The one from Twitter dated February 1937 - Usual mei (thinner) dated July 1936 (sanmei)1 point

-

Tamahagane is what separates Nihonto from all other swords, even other Japanese swords. It may not be the best steel; but it is the only one to offer up the hada and hamon activities that we all love, and some of us still struggle to understand. The fact that Japanese men were able to make this steel with such difficult raw material, using zero technology, and then make the finest blades ever seen in history, boggles the mind. And then they just happened to have the perfect rocks to be able to bring about the amazing polish that we still can't match. Wow.1 point

This leaderboard is set to Johannesburg/GMT+02:00